Avian flu has been detected in “very high concentrations” in milk, health officials announced.

The World Health Organization (WHO) said Friday that bird flu, also known as H5N1, has been found in raw milk, which is milk that does not go through standard pasteurization processes to kill bacteria.

Officials said pasteurized milk, which is standard at major retailers, remains safe.

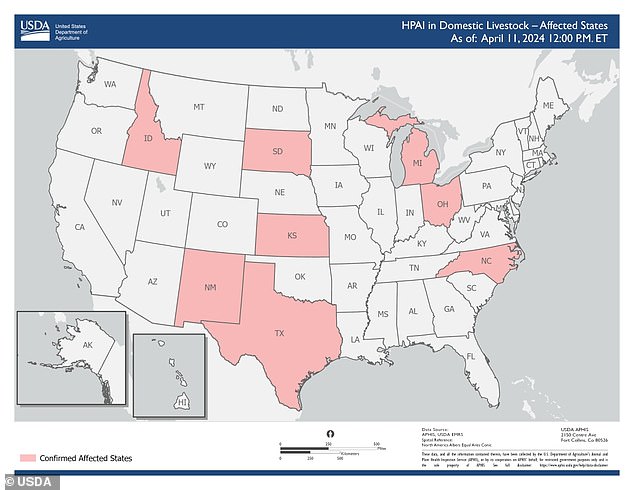

Bird flu has increased in cows and chickens across the United States, and animals on 29 farms in eight states have been affected, according to the CDC.

Last week, Dr. Darin Detwiler, former FDA and USDA food safety advisor, told DailyMail.com that Americans should avoid raw meat and liquid eggs while the outbreak in livestock was ongoing, as undercooked animal products are more likely to carry viruses and bacteria.

The World Health Organization said Friday that bird flu, also known as H5N1, has been detected in unpasteurized milk, although pasteurized milk remains safe.

The map above shows states with cattle herds that have been diagnosed with bird flu.

Avian influenza A(H5N1) first emerged in 1996, but since 2020, the number of outbreaks in birds has grown exponentially, along with an increase in the number of infected mammals.

The strain has caused the deaths of tens of millions of poultry, and has also infected wild birds and land and marine mammals.

Cows and goats joined the list last month, a surprising development for experts because they were not thought to be susceptible to this type of influenza.

Earlier this month, a dairy farm worker in Texas became the second American to become infected with bird flu. Authorities said his case was mild and he was recovering well.

Dr Wenqing Zhang, head of the WHO’s global influenza programme, said: “The case in Texas is the first case of a human being infected with avian influenza from a cow.”

“Cow-to-cow, cow-to-cow and cow-to-bird transmission has also been recorded during these current outbreaks, suggesting that the virus may have found other transition routes than we previously understood.”

“We are now seeing multiple affected cow herds in an increasing number of US states, showing another step in the spread of the virus to mammals.”

Dr Zhang said there was a “very high concentration of virus in raw milk” from infected cows, but experts were still investigating exactly how long the virus is able to survive in milk.

The Texas health department has said cattle infections are not a concern for the commercial milk supply because dairies must destroy milk from sick cows. Pasteurization also kills the virus.

“It is important for people to ensure safe eating practices, including consuming only pasteurized milk and dairy products,” Dr. Zhang said.

From 2003 to April 1 this year, the WHO said it had recorded 463 deaths out of 889 human cases in 23 countries, putting the case fatality rate at 52 percent.

Dr. Zhang noted that human cases recorded in Europe and the United States in recent years since the virus emerged have been mild cases.

So far, there is no evidence that H5N1 is spreading among humans.

And Zhang stressed that the A(H5N1) viruses identified in cows and in the human case in Texas did not show greater adaptation to mammals.

As for possible vaccines, if they were needed, Zhang said there were some in the pipeline.

“Having vaccine candidate viruses ready allows us to be prepared to quickly produce vaccines for humans, if necessary,” he said.

“For this particular H5N1 virus detected in dairy cows, there are a couple of candidate vaccine viruses available.”

In the event of a pandemic, there are about 20 influenza vaccines authorized for pandemic use and they could be tailored to the specific virus strain in circulation, he said.