BOOK OF THE WEEK

Everest, Inc.

by Will Cockrell (Gallery Books £20, 352 pages)

It’s one of the most striking images ever taken on a mountain: The image, from May 2019, showed a long line of hundreds of climbers spread out in single file on an icy knife edge just below the summit of Mount Everest.

They are all located in what is ominously known as the “death zone”, an altitude above 26,000 feet, where the human body begins to rapidly shut down due to a catastrophic lack of natural oxygen.

For some observers, the image represented the ultimate plundering of the unique splendor of the highest mountain in the world, all for commercial purposes.

It seemed a long way from that historic day in May 1953, when Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay became the first to reach the summit of Everest, as part of a large British expedition organized as closely as a military operation.

Until then, 14 expeditions had failed to conquer the 29,035-foot peak. Between that first ascent and 1992, only 394 climbers reached the summit.

The image, from May 2019, showed a long line of hundreds of climbers stretched out in single file on an icy knife edge just below the summit of Mount Everest.

Between 1992 and 2024, more than 11,500 achieved the same feat, almost all clients of a few mountain guiding companies, and all paying up to $100,000 (£80,000) for the privilege.

How did that happen? How can the highest place in the world, and one of the most dangerous, become a vacation you can buy, like a Caribbean cruise?

In this compelling and exhaustively researched book about the Everest industry, Will Cockrell, an experienced adventure writer, attempts to answer the question. At the same time, he addresses the complex moral questions involved: If you virtually eliminate danger, are you killing the spirit of adventure? And just because you have $100,000 to play with, should you be entitled to purchase such a notable personal achievement?

But the fact is that even if you are guided up the mountain, climbing stairs and hooking yourself to pre-placed ropes, while breathing bottled oxygen deposited along the way by your guides, a climb to Everest is still a powerful test of the heart. , fitness and resistance. And it is still a very dangerous place: steep, cold and windswept.

The fact that an industry has developed to take climbers to the summit does not eliminate all dangers, as the recent disappearance of a 40-year-old British climber, Daniel Paterson, and his 23-year-old Nepalese guide Pastenji Sherpa illustrates all too tragically. years.

Cockrell attributes the birth of the guiding industry to a wealthy Texan industrialist named Dick Bass, who had conceived a plan to climb the highest mountains on all seven continents. At noon on April 30, 1985, Bass climbed to the summit of Everest, on his fourth attempt, accompanied by veteran climber and filmmaker Dave Breashears.

Bass was the 174th person to reach the top of the world and, at 55, the oldest. She knew he was never a “real” climber and he didn’t want to be either.

Two weeks later, he appeared on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show and stated that usually “the only exercise I get is running through airports to catch a plane.” Millions of average Americans could then say, “So, that guy climbed Mount Everest.” I could do that.’

As Cockrell says, Bass “set in motion something that irrevocably changed the way people thought about Everest and mountaineering in general.”

Climbing Everest was becoming a commodity and, led by enterprising and qualified mountaineers, guiding companies began to arrive in droves. Everest Base Camp, the destination for anyone who would attempt to reach the summit on the Nepalese side, is itself, at 17,600 feet, a monumental height. for most people. To the early pioneers, it would now be unrecognizable.

Row after row of tents, carefully arranged like at Glastonbury, stretch across more than a mile of rock and ice. Impressive stone shelters act as tents, cooking stations and, during downtime, casinos and lounges.

Briton Daniel Paterson has not been seen since reaching the summit of Everest last Tuesday.

Nepalese guide Pastenji Sherpa, 23, who was with Paterson, also remains missing.

You can grab a good cup of coffee, a fresh croissant, and a massage before happy hour, and then maybe an art show, followed by some late-night poker accompanied by whiskey.

This didn’t sit well with everyone. Hillary said: “Sitting at base camp drinking cans of beer, I don’t particularly consider it mountaineering. It’s good that one can go on vacation to the beach or climb Everest.’

And climber and guide Pet Athans observed: “People think it’s still an adventure: it’s more of an adventure to discover the New York subway system.” But for Cockrell, the climbers the guides educate don’t spoil the mountain, they share it. They may not be experienced, but they are there for as good a reason as anyone else. Getting to the top is a great challenge, no matter how much help you receive.

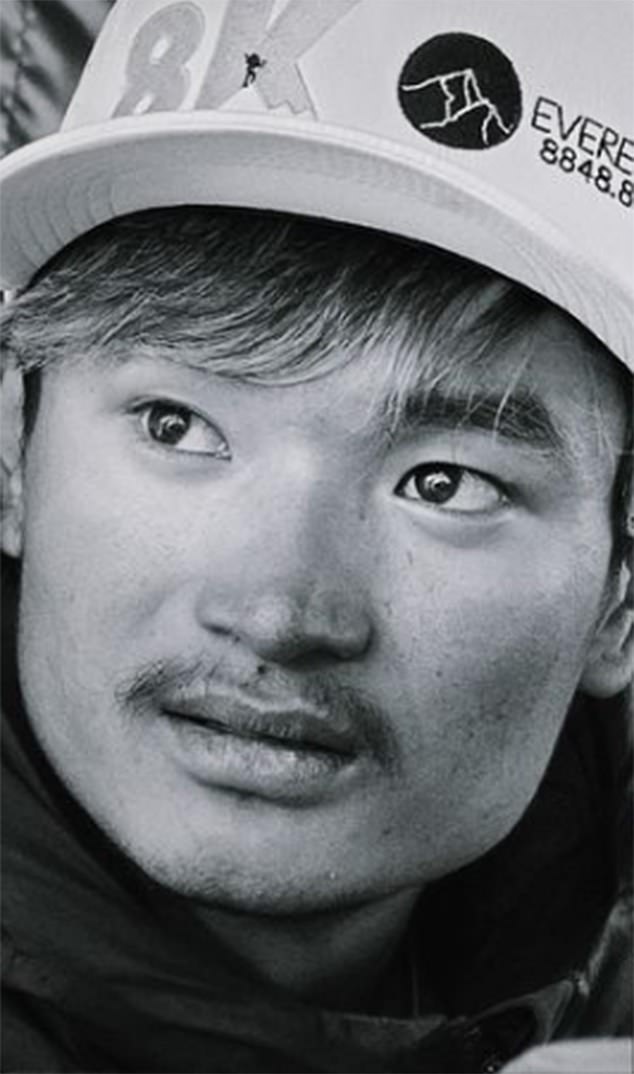

The famous ‘conga line’ photograph was taken by a Nepalese mountaineer called Nirmal Purja, known as Nims and the most famous climber in the world.

Nims is now the figurehead of Nepal’s success on Everest. Born in 1983, Nims joined the Gurkhas at age 20 and was later accepted into the Navy Special Boat Service, a unit similar to the US Navy SEALs. So you could say he’s a Tough man.

When he took up climbing, he climbed three 8,000m peaks in five days: Everest, Lhotse and Makalu. In 2018, he announced that he would climb all 8,000m peaks in seven months, while the previous record was more than seven years.

Nims climbed all 14 peaks in just over six months. It was a titanic achievement, but also a tribute to his organizational capacity, with plenty of oxygen, dozens of climbers fixing the routes and a helicopter to get to the next base camp as quickly as possible.

This compelling and exhaustively researched book on the Everest industry is written by Will Cockrell, an experienced adventure writer.

As his profile skyrocketed, he landed book and movie deals and formed a guiding company, Elite Exped. She can ask for a million dollars for a one-on-one private guide, which is what she allegedly charged Princess Asma Al Thani of Qatar to take her to the top of Everest in 2022. I’m sure she could afford it.

Nims is not to everyone’s taste (for some he is too selfish, an empire builder), but he is the face of the new Nepali leaders who dominate Everest and the Himalayan climbing industry.

The largest companies working in the mountains are now owned by Nepalis, their staff and management are Nepalis. And if a fortune is to be made from wealthy climbers who want to experience the roof of the world, then it is preferable that the money go primarily to the people who live there.

This is very much Cockrell’s view in this fascinating book, and if you approve of wealth creation (as I do), then what is happening on Everest is largely a good thing. I just wish he’d be a little less enthusiastic about it.

As Venice is not alone in discovering this, tourism can be harmful (even arduous adventure tourism) and the beauty of the world’s wild places needs to be cared for. If exploration and adventure become too easy and safe, then a fundamental part of what it means to be human is lost.