Elephants are already known for their remarkable level of intelligence, similar to that of humans.

But a new study shows that males in groups are conveying a sophisticated message, even if it sounds like a primitive growl to human ears.

Adult male African elephants emit a deep, resonant growl to their herdmates to signal it’s time to move on, experts say.

A surprising audio captured by biologists reveals that this call ‘let’s fight’ is repeated throughout the pack ‘like a barbershop quartet’.

Adult females are already known to use the “let’s go rumble” but new recordings document the technique in males for the first time.

Scientists have documented that male elephants use “go” sounds to signal the start of group sorties.

The new study was led by Caitlin O’Connell-Rodwell, a research associate at Stanford University’s Center for Conservation Biology.

“These calls show us that there is much more going on in their vocal communication than previously known,” he said.

The experts studied African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana) at the Mushara waterhole in Etosha National Park, Namibia, one of the largest national parks in Africa.

Although the African elephant is a social mammal that moves in herds, these groups are made up of females and their young.

Males leave the herd when they reach maturity, around 10 to 19 years of age, and as adults they typically live alone or in small “bachelor” groups.

The experts studied elephants at the Mushara waterhole in Etosha National Park, Namibia, one of the largest national parks in Africa.

Male African elephants (pictured) leave the herd when they reach maturity, around 10 to 19 years of age, and as adults they typically live alone or in small “bachelor” groups.

In Etosha National Park, experts used recording equipment including buried microphones and night-vision video cameras to capture movements and vocalizations inaudible to human ears.

They noticed that the characteristic noise preceded the water well’s exits, suggesting that it had important meaning.

Typically the call came first from the oldest or most dominant male in the group before the other males repeated it as if in agreement.

Each elephant waited until the previous call was almost over before adding its own, creating a harmonious pattern of turn-taking similar to a barbershop quartet.

The findings are particularly surprising because men are generally thought to have loose social ties, according to O’Connell-Rodwell and her colleagues.

“We found that this vocal coordination occurs in groups of closely associated and strongly bonded individuals and rarely occurs among more loosely associated individuals,” they say.

The “come on” noises observed in male elephants have striking similarities to those previously recorded in female elephants.

In fact, the team hypothesizes that male elephants likely learn the behavior when they are young, before leaving the herd.

“They grew up in a family where all the female leaders participated in this ritual,” O’Connell-Rodwell said.

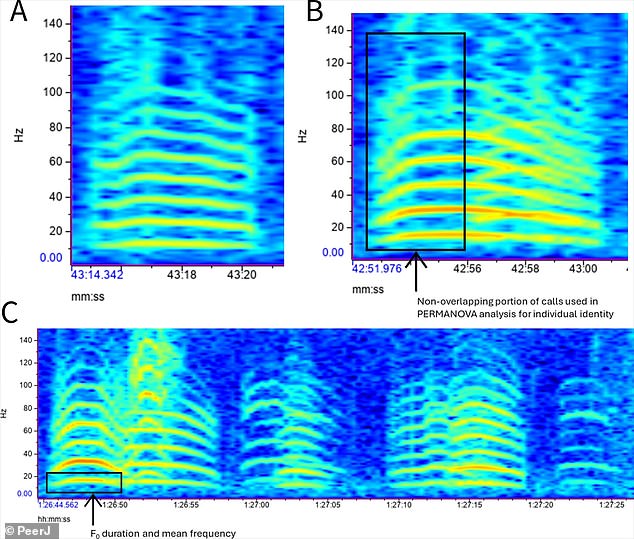

Three spectrograms depicting three different coordinated rumbling vocalizations of male elephants during game play. A spectrogram is a graph showing the intensity of a signal over time for a given frequency range.

Male elephants, often thought to have loose social bonds, use such sophisticated vocal coordination to trigger action.

We believe that as they mature and form their own groups, they adapt and use these learned behaviors to coordinate with other males.

Sadly, African elephant populations have plummeted over the past century due to poaching, retaliatory killings for crop theft, and habitat fragmentation.

Care should be taken to avoid hunting older male elephants with social connections, as their removal could disrupt social cohesion and mentoring structures within elephant populations.

“These findings provide further support for the idea that mature males, and perhaps certain individuals such as those leading the LGR events here, are important to male elephant society,” the team writes in their paper, published in PeerJ.

‘Other variables, such as group size, noise frequency or level of attachment, could also affect the duration of the outing and warrant further investigation.’

Another recent study found that African elephants call each other by name—in other words, they use unique sounds depending on which elephant they’re communicating with.

The findings suggest that elephants may be capable of abstract thinking, making them much more socially complex mammals than previously thought.