Thousands of NHS patients plagued by agonizing knee pain will be offered “growing” joint replacements.

The long-term procedure to repair knee cartilage damage has been approved by the NHS spending watchdog after 20 years of research.

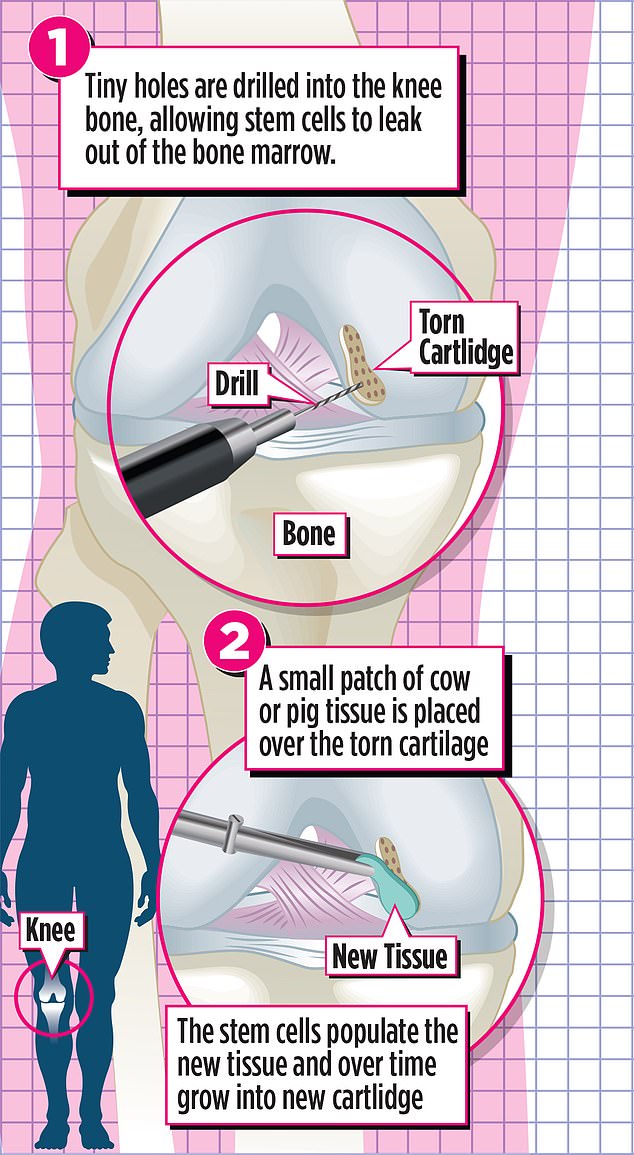

The technique, known as one-step scaffold insertion, involves extracting stem cells from the patient’s problem joint and growing them within animal tissue.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) concluded that many patients suffering from debilitating knee injuries saw their mobility “significantly improved” after surgery.

Every year, around 10,000 Britons need treatment for torn cartilage injuries, usually in the knee. This is where the tough but flexible ‘cushion’ that prevents bones from rubbing together in the joints breaks down, often due to strong impacts during sporting activities or simply rotating the knee too much while the foot is planted.

Rebecca Bennett (pictured with her husband), from Somerset, was one of the first people in the UK to benefit from autologous chondrocyte implantation almost 20 years ago.

Every year, around 10,000 Britons need treatment for torn cartilage injuries, usually in the knee. This is where the tough but flexible ‘cushion’ that prevents bones from rubbing against each other in the joints breaks down, often due to strong impacts during sporting activities (file image)

Once cartilage has been damaged, it does not heal on its own.

It causes pain, swelling, and frequent joint seizures. Many patients find that the injured knee also gives way easily, increasing the risk of dangerous falls.

Young adults who tear knee cartilage are also much more likely to develop agonizing osteoarthritis, where the cartilage wears down so excessively that the bones in the knee grind against each other later in life. Some end up needing knee replacement surgery when they are in their 40s and 50s.

This is a major operation that involves opening the knee and replacing the joint with a metal or plastic implant. Knee replacements take about a year to recover from, and sometimes the implant can become infected or worn out, leading to its removal. About one-fifth of patients will need a second joint replacement.

About two decades ago, researchers developed an innovative solution to repair tears in knee cartilage before they caused irreversible damage. The procedure, called autologous chondrocyte implantation, involves regrowing cartilage in a laboratory.

Bone marrow (the soft, spongy material found inside bones) is removed from patients’ hips using a long needle. Subsequently, stem cells, which have the ability to develop into new, healthy cartilage, are collected from the bone marrow and grown in a dish. Several weeks later, the patient undergoes a second procedure to implant the cells into the knee, where they continue to grow and become fully functioning cartilage.

While effective, autologous chondrocyte implantation is very expensive: growing stem cells in a laboratory can cost up to £17,000. It also requires two invasive operations.

But the new one-step scaffold insertion procedure offers similar results with a single operation. During the hour-long surgery, surgeons drill small holes in the knee bone while the patient is under general anesthesia. This allows stem cells to leave the bone marrow.

A small patch of cow or pig tissue is then placed over the torn cartilage to act as a kind of scaffold on which the stem cells settle. Over the next six to 12 months, the stem cells grow into new cartilage, strengthening the knee, relieving pain, and restoring motion.

The method costs a fraction of autologous chondrocyte implantation: animal tissue scaffolds cost between £1,000 and £2,000 and there is no need to grow cells in a laboratory.

“This is potentially very good news,” said Ian McDermott, a knee surgeon at London Sports Orthopedics who has performed the one-step procedure on hundreds of private patients. “It has an 80 percent success rate after five years and is a fraction of the cost of current techniques.”

The main operation that involves opening the knee and replacing the joint with a metal or plastic implant. Knee replacements take about a year to recover from, and sometimes the implant can become infected or wear out.

However, experts maintain that the procedure will not cure all patients. Studies suggest it is most effective on small cartilage tears. Patients who undergo the operation may also need a knee replacement in the future.

However, those who have already received stem cell therapy for torn cartilage say it has changed their lives.

Rebecca Bennett, from Somerset, was one of the first people in the UK to benefit from autologous chondrocyte implantation almost 20 years ago.

The 43-year-old was a teenager when a freak slip caused her knee to bend backwards, causing years of agony. “It was the worst pain I’ve ever felt in my life,” Rebecca says. “And I have had four children.”

The cartilage in his knee had been damaged. Numerous operations followed, none of which solved the problem. ‘My knee was suddenly dislocated. The whole joint looked like a piece of floating jelly.

Doctors warned he could end up in a wheelchair, but in 2005 he was offered the chance to take part in a trial at London’s Orpington Hospital, where surgeons were testing the new technique.

“As soon as I woke up I knew it worked, even before I got out of bed,” adds Rebecca. ‘It felt completely different. Twenty years later my knee is still as good as ever. He gave me back my freedom.’