As the last British boxer standing reached the quarter-finals, the young man who would have been the favourite to light up the City of Light by winning the most golden prize in the Olympic ring was lunching in London’s West End.

The fact that Moisés Itauma was cutting into a juicy, expensive steak instead of tearing apart heavyweights in Paris was deeply moving.

Ask the teenage phenomenon why he turned down his place in the Great Britain team and he fiddles with his fork as he searches for a sensible explanation. Finally, he says: “My priority was to make my mother feel, shall we say, comfortable.”

He feels more comfortable now than he did talking about the hardships of his upbringing.

Poverty has been the breeding ground for many boxing champions, but the extent of that poverty during Itauma’s childhood on the Kent coast is a stark revelation.

The fact that Moisés Itauma was cutting into a juicy, expensive steak instead of tearing apart heavyweights in Paris was deeply moving.

Ask this teenage phenomenon why he turned down his designated place on Team GB and he fiddles with his fork as he searches for a sensible explanation.

Boxing has been the salvation of countless young people in various ways.

“Let’s put it this way,” he says carefully, “there was always breakfast, but often when we asked what we were going to have for dinner, our father would say: sleep for dinner.”

In post-war Britain, it was common to fight hunger by pulling up the covers. Not so much a decade ago, when Itauma followed his Romanian mother, Nigerian father and two brothers from the Slovakian village of Kezmarok to the port town of Chatham.

The initial hardships were worth it for a family fleeing racism, something that will be familiar to anyone who has watched professional football in much of Eastern Europe. Itauma says: “We couldn’t take the stares and the abuse any longer. Especially my father. He decided it was time to go to England. My grandmother looked after me, so I was the last one out, aged eight.”

As the standard of living in his new home increased, so did Itauma’s weight, which was excessive thanks to fast food. He recalls: “As a child, I weighed almost 100 kilos.”

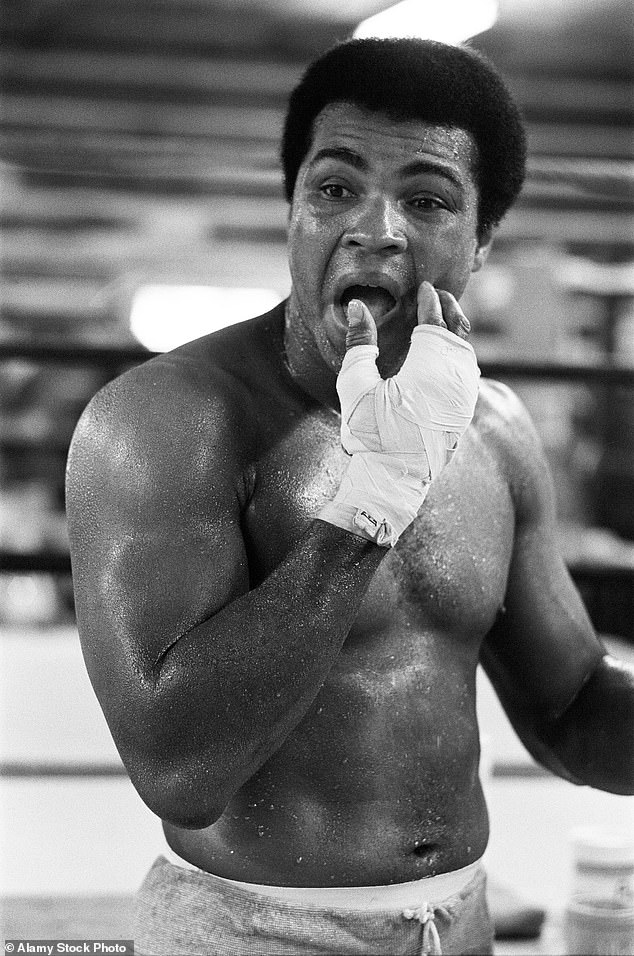

Boxing has been the salvation of countless young men in various ways. Taking the toughest sport seriously – “I took boxing seriously after I got bored of football” – has turned this pot-bellied lad into a lean, fast, muscular 75kg adult threat. More Muhammad Ali than Tyson Fury, the latter one of several giant names he has sparred with. His report in the gym: “Tyson gave me a scare in some rounds, but I gave in a bit in others.”

The long-overdue decision on the Olympics became final when she signed a professional contract on her 18th birthday. Frank Warren, who has just donated £1m to the BoxWise charity, which helps disadvantaged youngsters, was generous in donating the two Chatham houses in which the once-impoverished Itauma has already invested.

“It was the only option,” the fighter said. “The one I had to take even though Rob McCracken had told me that I was ahead of Delicious Orie in the fight for the super heavyweight spot in Paris.”

Coach McCracken has brought a host of world champions into his Olympic ranks, including Anthony Joshua, Amir Khan, James DeGale and Nicola Adams. Had Itauma chosen differently, he would be under less pressure now after what will be seen as a devastating Paris 2024, even if light-middleweight Lewis Richardson somehow gets past the guaranteed bronze that was beyond the other five members of the Great Britain team, including The Delicious One, who like Moses and AJ has Nigerian ancestry.

Frank Warren, who has just donated £1m to the BoxWise charity, which helps disadvantaged young people, was generous in donating the two Chatham houses that the once-impoverished Itauma has already invested in.

More Muhammad Ali than Tyson Fury, the latter one of several giant names he has sparred with.

Itauma said: ‘The one I had to do even though Rob McCracken told me I was ahead of Delicious Orie for the super heavyweight spot in Paris’

However, even though she is travelling to Paris this week to watch the final, Itauma has no regrets.

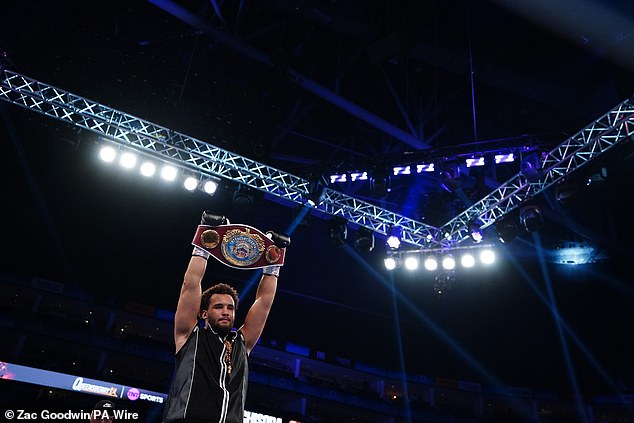

“None,” she says. “I’ve also done the best for my career. At 19, I’m a year and a half and ten professional wins ahead of what I would have achieved if I had gone to the Games. And I’m much closer to fighting for a world title.”

He has also had the rare distinction of being undefeated as an amateur. Those 24 wins preceded ten professional victories in an all-time unbeaten record, partial details of which speak to his growth as a fighter. In two of his first wins as a pro, he was taken the six-round distance. “Looking back,” he says, “I tell myself I should have stopped those two like everyone else. But then again, they gave me the experience of a few rounds.”

That’s more than the other eight could manage. Even Mariusz Wach, the giant Polish veteran and arch-rival against champions who was brought to No. 2 on the Derek Chisora-Joe Joyce undercard the other night to offer a more prolonged resistance, was knocked out in less than two rounds.

The blows are so severe that his manager, Warren’s son Francis, says: “It’s a nightmare to find sparring partners, let alone men to fight him.”

“I’m willing to take on any big name I can think of,” Itauma says. Hopefully, money will talk in that regard. The Saudis bankrolling the multimillion-dollar Fury and Joshua fights are interested, having seen him in destructive action on the May night when the Gypsy King lost the undisputed world title to Oleksandr Usyk in Riyadh.

That occasion also gave him the chance to mingle with ring legends who were invited to a royal reception. He says: “I enjoyed being in the company of greats like Mike Tyson and Manny Pacquiao. I saw how they deal with fame. I loved watching Naseem Hamed when I was a kid. But I don’t have any idols. I am my own boxer.”

His older brother Karol is also on the Queensberry roster and when his unbeaten record was lost, Moses described himself as “heartbroken”.

Karol describes his younger brother as “cold.” With all due respect, let me modify that with another word: calm. Moses is as calm and calculating in conversation as he is in the ring. Also, despite his Romanian origins, he is as polite and proper as an English gentleman. What do you know? British upbringing is still a good part of what it used to be. It still breeds aspirations.

Itauma has expressed his ambition to break Mike Tyson’s record as the youngest heavyweight world champion of all time. Iron Mike was 20 years, four months and 22 days old when he inflicted a second-round knockout on Trevor Berbick in November 1986 to seize the WBC title. Given that to surpass that record he would have to win one of the belts in May next year, it is unlikely, given the stalemate at the top of the heavyweight division.

Usyk, Fury and Joshua are locked in a schedule of fights and rematches involving every title in the alphabet that will keep them occupied until the end of 2025.

He has also carried with him the rare distinction of being undefeated as an amateur.

Itauma has expressed his ambition to break Mike Tyson’s record as the youngest heavyweight world champion of all time.

It is no surprise that this Bible-reading Christian has changed the name he was given as a child in Slovakia – Enrico – to one from the Old Testament.

To which Itauma offers this quiet reflection: “I feel like I’m ready for any of them now. Any time. It doesn’t matter what my team thinks. But if beating other contenders before then gives me more experience, that’s fine too.”

Speaks a man grateful for the God-given talent of quick feet and swift hands with which to detonate blows of awesome concussive power.

It is not surprising that this Bible-reading Christian has changed the name he was given as a child in Slovakia – Enrico – to one from the Old Testament. The wisdom of Moses is truly unusual in someone so young.