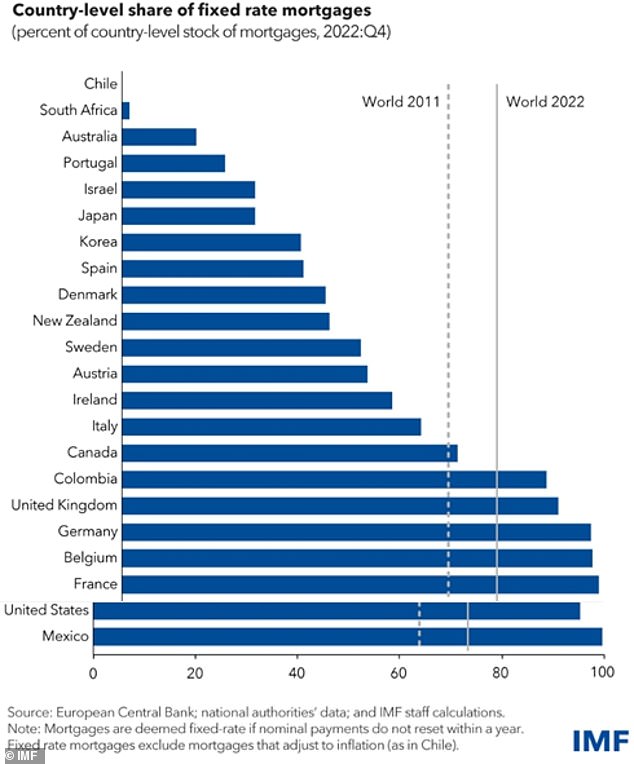

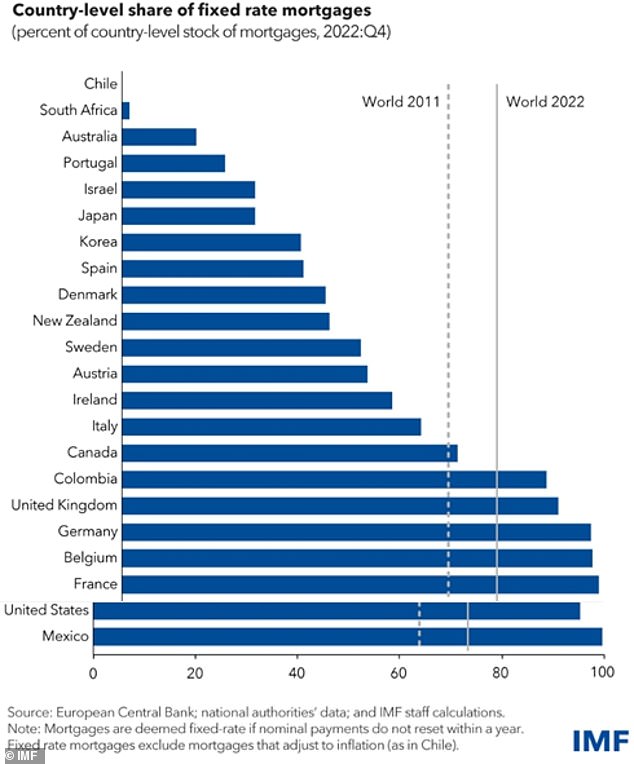

Australians are more likely to experience mortgage stress than almost anyone in the world because so few borrowers here are on a fixed interest rate, according to a new IMF report.

Globally, Australia has one of the lowest fixed-rate mortgage take-up rates in the world, the International Monetary Fund says.

Global finance chiefs have also raised concerns that Australians have some of the highest levels of household debt in the world and an undersupply of housing leading to an affordability and rental crisis.

Australia came third in an IMF ranking of 22 countries for the proportion of fixed-rate borrowers, behind only Chile and South Africa.

Borrowers hit hardest in Australia

Now that only 1.4 per cent of Australian borrowers are on a fixed interest rate, that means 98.6 per cent of monthly mortgage payments automatically increase when the Reserve Bank of Australia increases interest rates. interest.

This has led to higher rates of mortgage stress, where borrowers spend 30 percent or more of their pre-tax salary on home loan payments.

Australians are more likely to experience mortgage stress because so few borrowers have a fixed interest rate, according to a new IMF report (file image pictured).

Australia was third in the IMF’s ranking of 22 countries for the proportion of fixed-rate borrowers, behind only Chile and South Africa.

In most other countries, the effects of policy rate increases are not immediately felt, but in Australia, monthly mortgage payments have increased by 67.7 percent since mid-2022.

“Our results indicate that monetary policy has greater effects on activity in countries where the proportion of fixed-rate mortgages is low,” the IMF said.

‘This is because homeowners see their monthly payments increase with policy rates if their mortgage rates adjust.

“By contrast, households with fixed-rate mortgages will not see any immediate difference in their monthly payments when official rates change.”

In February, just 1.4 per cent of borrowers by value were on a fixed rate compared to 98.6 per cent on a variable rate, new lending data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics revealed.

But in October 2021, 43.6 per cent of borrowers were on a fixed rate compared to 56.4 per cent on a variable rate, when RBA interest rates were at a record low of 0.1 per cent. cent and banks offered variable rates starting with a ‘two’.

Even in mid-2022, when interest rates were still at record lows, Australia had a much lower proportion of fixed-rate mortgages compared to the global average, with fewer than one in five locking in a rate for multiple years.

Since May 2022, the Reserve Bank has raised interest rates 13 times, and in November the most aggressive rate increases in a generation took the cash rate to a 12-year high of 4.35 per cent.

A borrower with an average mortgage of $598,624 has seen their monthly variable rate payments increase from $2,301 to $3,858, which translates to an increase of 67.7 percent.

Borrowers with a 20 per cent mortgage deposit are paying $18,696 more a year in repayments as the Commonwealth Bank’s variable rate rose to 6.69 per cent, up from 2.29 per cent.

ME Bank offers Australia’s cheapest fixed rate of 5.79 per cent for two years, but all major banks have variable or fixed rates starting with a ‘six’.

Unaffordable housing

Despite the higher rates, house prices in Sydney have risen 25 per cent since the pandemic, but in Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide they have soared by more than 55 per cent, CoreLogic data showed.

Australia now has a rental vacancy rate of just one per cent.

“During the pandemic and associated lockdowns, the combination of low rates and structural changes led to rapid growth in housing prices globally, adding to already elevated pre-pandemic levels in some countries,” the IMF said. .

‘House prices often grew faster than incomes, reducing affordability and driving potential buyers to rent.

“This, combined with the decline in new construction, boosted rents in many countries.”

On a global scale, Australia has one of the lowest levels of fixed-rate mortgages in the world (pictured are houses in Oran Park, south-west of Sydney).

Higher debt levels

The IMF also noted that Australia also had an undersupply of housing and higher debt levels as a result of less restrictive loan-to-value (LTV) ratios, where a loan can finance a greater proportion of the property purchase.

“Countries such as Australia and Japan appear to have stronger real estate channels for the transmission of monetary policy, with low shares of fixed-rate mortgages, less restrictive LTV limits, high household debt (only to some extent in Japan) and a somewhat high proportion of the population living in areas with restricted housing supply,” the IMF stated.

But unlike Japan, Australia has record immigration and the fastest population growth since the early 1950s.

That means there is a shortage of homes in Australia, leading to unaffordable prices and skyrocketing debt.

The IMF noted that Australia had some of the highest debt levels in the world.

“Similarly, household debt is below 50 percent of GDP in some (for example, Chile, Colombia and Israel) and exceeds 100 percent of GDP in others (Australia, Canada and Norway).” said.

Australia’s household debt-to-income ratio of 211 per cent is the third highest in the world after Norway’s 247 per cent and Switzerland’s 222 per cent.

Australia now has a rental vacancy rate of just one per cent during a housing affordability crisis (pictured, a rental queue in Bondi)

Shady consumers

It’s no wonder Australians are pessimistic, as the Westpac-Melbourne Institute consumer confidence index for April shows pessimists far outnumbered optimists when it comes to the economy.

The monthly index fell another 2.4 percent this month to 82.4 points, putting it well below the 100 mark, where optimists outnumber pessimists.

Westpac senior economist Matthew Hassan said that, apart from the recession of the early 1990s, the prolonged gloom was among the worst since the bank began surveying consumers in the mid-1970s.

“The pessimism that has dominated the consumer mood for almost two years still shows little sign of improving,” he said.

‘In fact, aside from the deep recession of the early 1990s, this is easily the second-longest period of deep consumer pessimism since we started surveying in the mid-1970s, and all other declines in sentiment lasted nine months or less.

“The April sentiment update suggests that consumers continue to expect progress on inflation and associated cost of living pressures to be slow.”