Thousands of child deaths have been linked to the increased use of pesticides on common crops.

Researchers at the University of Chicago have found that farmers have increased their use of chemical pesticides to protect their crops from insects as the number of pests feeding on their produce increases.

As farmers used more pesticides on their crops, the infant mortality rate increased by almost eight percent, totaling 1,334 additional infant deaths.

For every one percent increase in pesticide use, there was a 0.25 percent increase in the infant mortality rate.

Behind the insect surge, researchers found, is a rapid decline in bat populations due to white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that kills more than a million bats each year in North America.

The researchers found that for every one percent increase in pesticide use, there was a 0.25 percent increase in the infant mortality rate.

Farmers have long turned to the winged animals as natural pesticides because they eat at least 40 percent of their body weight in insects each night, meaning fewer bats mean swarms of more insects that drive pesticide use.

The research team found that the decline in bats led to a 30 percent increase in the use of synthetic pesticides.

But the chemicals have been linked to an increased risk of birth defects, low birth weight and stillbirth.

Since WNS was first discovered in the US in 2006, it has killed nearly 7 million bats in North America.

Dr Eyal Frank, study author and adjunct professor at the University of Chicago, said: ‘Bats have gained a bad reputation as something to be feared, especially after reports of a possible link to the origins of Covid-19.

“But bats add value to society in their role as natural pesticides, and this study shows that their decline can be harmful to humans.”

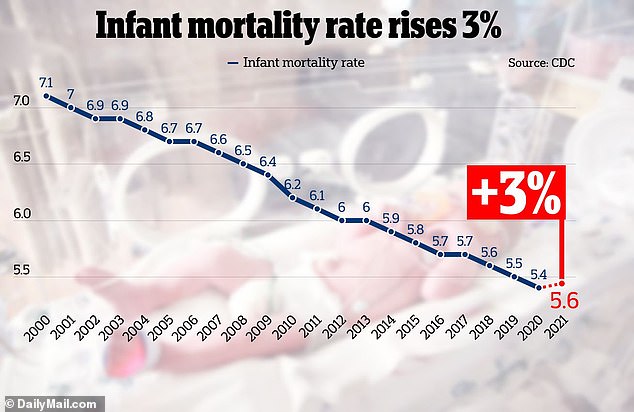

The findings come at a time when infant deaths are on the rise in the United States, which researchers have attributed to premature births, maternal complications during pregnancy and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

In it study Published in the journal Science, Dr. Frank analyzed 245 counties that reported cases of white-nose syndrome (WNS), which gets its name from the white fungus that grows around the snouts and wings of infected bats.

The fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, thrives in cold climates and infects bats as they hibernate during the winter.

The team found that in counties reporting WNS, farmers increased their use of synthetic pesticides by 31 percent to compensate for the loss of bat populations and protect their crops from the resulting increase in bat-eating insects.

In those counties, infant deaths from natural causes increased by eight percent, representing 1,334 additional deaths, between 2006 and 2017.

While this is only a preliminary link, researchers believe it could offer insight into the human cost of declining bat populations.

White-nosed bat populations are declining due to a disease called white-nose syndrome.

Dr Frank said: ‘When bats are no longer there to do their job of controlling insects, the costs to society will be very large, but the cost of conserving bat populations will probably be lower.

More broadly, this study shows that wildlife adds value to society and we need to better understand that value in order to inform policies aimed at protecting it.

The study sheds new light on the causes of infant mortality, which has increased by about three percent in the past year, according to the latest CDC data.

According to the CDC, the leading causes of infant mortality in 2021 were birth defects, premature birth and low birth weight, injuries such as suffocation, pregnancy complications, and SIDS.

According to the Center for Biological Diversity, when the disease spreads to a group of hibernating bats, it kills 70 to 90 percent of them, but in some cases it can wipe out entire colonies.

This could put more than half of North America’s bats at risk of serious decline in the next 15 years, according to researchers at the nonprofit Bat Conservation International.

WNS has been detected in 34 US states and seven Canadian provinces.

Bats have also been shown to help pollinate plants such as banana and mango trees and spread seeds in rainforests. However, these animals can also transmit rabies, so experts recommend avoiding touching them.

Some research has also suggested that SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind the Covid-19 pandemic, originated in bats and either reached humans through another species or mutated enough to be able to spread between people.