John Moore is on a mission to stop the melting of the world’s widest glacier, nicknamed the “glacier at the end of the world” for the havoc it could unleash on the world.

The 74,000-square-mile Thwaites Glacier, located on the western edge of Antarctica, is losing about 50 billion tons more ice than it is receiving with new snowfall.

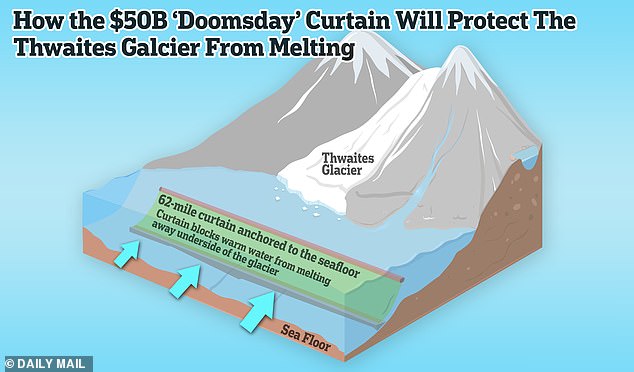

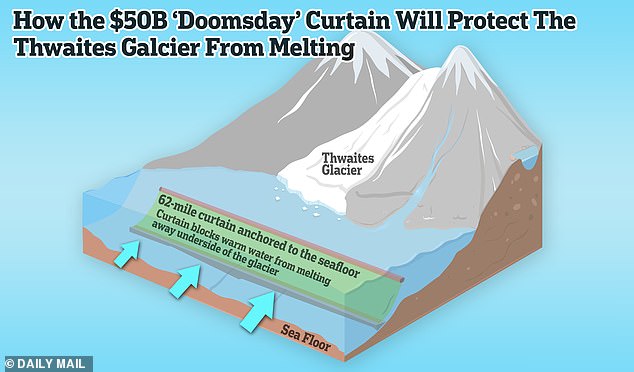

Professor Moore told DailyMail.com that he and his colleagues want to stop the glacier’s retreat by placing a 62-mile-long curtain in front of it to stop warm ocean water from melting the underside.

Its melting alone already contributes about four percent to global sea level rise, and if it were to melt completely, it would raise sea levels around the world by up to 10 feet, which is how it earned its claim. nickname.

The Thwaites Glacier has proven especially vulnerable to climate change and is melting faster every year. If the Earth continues to warm and the glacier melts completely, it could raise sea levels by up to 10 feet.

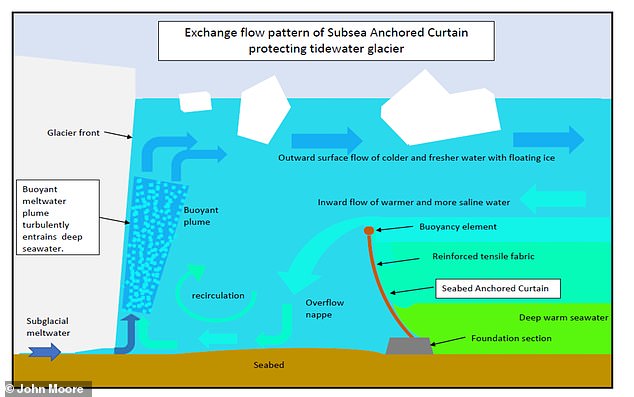

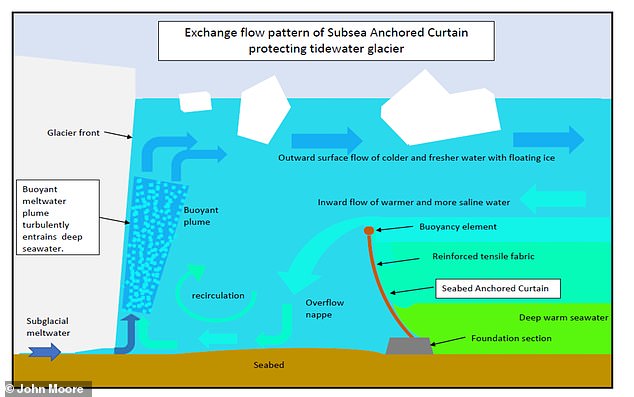

The proposed curtain would be anchored to the sea floor, where it would protect the glacier from the warm currents that corrode its underside.

That amount of sea level rise would put coastal cities around the world at serious risk of major flooding.

Their plan: Anchor a giant curtain across 62 miles of seafloor to prevent most of the warm water from melting the glacier from below.

The estimated cost: $50 billion. Funding for the project could come from a combination of grants and government funds.

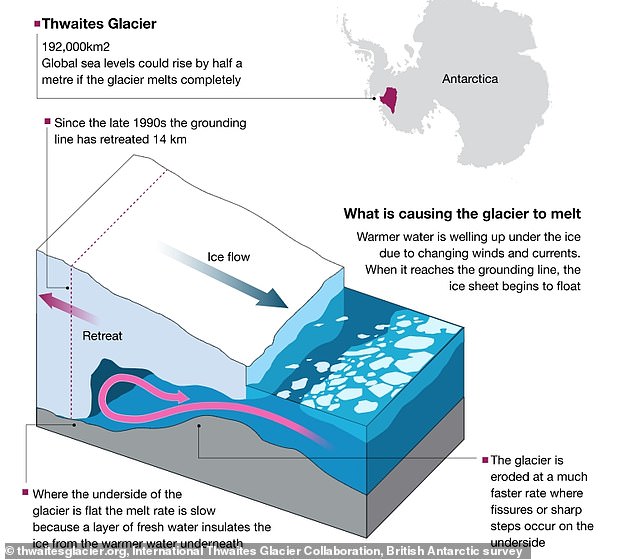

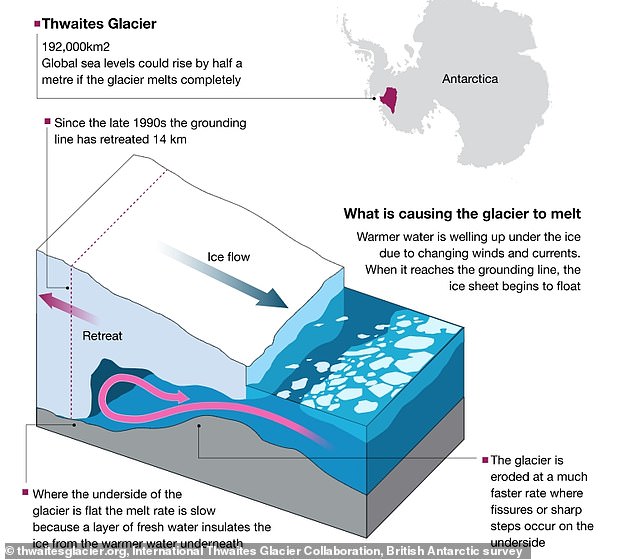

Most of the ice Thwaites loses comes from below, where warm, salty waters circulating in the deep sea wear it away.

As the climate warms, these deep ocean currents become warmer, melting the bottom of the glacier even faster.

With warmer ocean temperatures, the winter refreezing cycle makes less and less effort to replenish melted ice.

The huge face of the Thwaites Glacier hides a thinning underside. John Moore of the University of Lapland wants to stop this thinning to save the glacier

The warm water flowing under the Thwaites Glacier melts it. Once enough ice has been removed from the bottom, the leading edge will break, or crack and fall off.

Occasionally, the glacier disintegrates, the scientific term for the collapse of a large portion of a glacier’s surface.

But this is only the external and obvious sign of the much more serious problem of underwater melting.

Before the industrial revolution, when humans began belching millions of tons of CO2 and other greenhouse gases into Earth’s atmosphere, Thwaites and other glaciers had normal cycles of thinning and thickening.

In winter, the glacier would grow as the ice thickened, and in summer it would recede as the ice thinned.

However, as the planet warms, much more thickening than thinning occurs.

To some extent, this process would occur independently of global warming, said John Moore, a research professor of climate change at the Arctic Center at the University of Lapland in Finland.

However, at a certain point, the melting is simply too much.

“Beyond the tipping point, glaciers like Thwaites simply collapse regardless of CO2 concentration because the reinforcement they need to remain stable disappears as the floating platform thins, like kicking off a strut supporting a fence. ” he told DailyMail.com.

“So if we want to replace the buttresses, we have to mimic nature and allow the platform to thicken again and reinforce itself,” Moore said. “The way to reduce snowmelt is to block some of the warm water that reaches it.”

This is where the curtain comes in.

They plan to anchor a curtain to the bottom of the Amundsen Sea, preventing underwater currents from hitting the underside of the Thwaites Glacier.

Supported by a floating top edge and anchored at the bottom, the curtain would float on the ocean floor, invisible from the water surface.

Getting it into place without damaging the glacier won’t be a problem, Moore said.

“We would put the curtain very far from the glacier, simply blocking the warm water in deep channels where they are narrow and accessible,” he said.

This graphic from John Moore and his team shows how the curtain would work. Deep, warm seawater (below right) flows toward the glacier, but the curtain would block most of it. However, some would flow over the summit, where it would mix with fresh water melting from the glacier (center). Then, instead of undermining the glacier, these mixed waters would flow outward and away from the glacier (top right)

The Thwaites Glacier, at the western edge of Antarctica, is poised to raise sea levels by 10 feet if it melts completely.

The biggest challenges, Moore said, have less to do with preventing further damage to the glacier and more to do with the safety of the people putting up the curtain.

“The harsh conditions, the short working season with sufficient natural light and the danger of the numerous icebergs around” are the biggest challenges, he said.

It will still be years before the curtain is installed, but Moore and his colleagues at the University of Cambridge are now working on computer simulations to get the design right, as well as “some tests in small-scale tanks, basically fish tanks.” .

Next, they plan to install a prototype on the River Cam in Cambridge next summer.

“We also plan to test a set of 10 different designs in the Norwegian fjord to see how they perform under realistic currents and wear,” he said.

“Then, if there are no serious problems, we will try it in a glacial influx fjord in Svalbard.”

If all this goes as planned, Moore and his team would see if the Greenlanders wanted to use them and, of course, if a deal could be reached to put up a curtain in Antarctica to protect the Thwaites Glacier.