Having played professional rugby for almost 20 years, former British Lions captain Alun Wyn Jones was used to pushing his body hard, so when three years ago he began to occasionally become breathless and felt as if his heart pounding, he simply shrugged his shoulders.

“You can have a fast heart rate after drinking caffeine, so I thought it might be due to a strong cup of coffee,” says Alun, 39, who lives near Swansea with his wife Anwen, a university professor, and their three. daughters.

And Alun rationalized that, as “about 90 per cent of my time was spent running”, being out of breath after a match was to be expected, even for him, the world’s most capped international rugby player, with 158 appearances. with Wales.

However, medical checks he underwent before signing for a new team in the south of France last year revealed his optimism was misguided.

To Alun’s horror, checks discovered he had a serious heart problem: atrial fibrillation, or AF, which means his heart beats erratically, putting him at significantly higher risk of suffering a stroke.

After medical checks, Alun Wyn Jones discovered he had a serious heart problem: atrial fibrillation or AF, which means his heart beats erratically, putting him at greater risk of suffering a stroke.

The condition affects around 1.4 million in the UK, and cases are increasing, even among relatively young and physically fit people.

While the diagnosis was “a huge shock,” Alun says it was also “actually a bit of a relief.” ‘It connected all the dots: For about 18 months to two years before my diagnosis, I felt tired and wondered if I had chronic fatigue.

‘My sleep was being interrupted and I had fleeting palpitations in my chest and felt a little breathless. But my symptoms were so innocuous that I dismissed them.

In fact, it is the innocuous nature of the symptoms (which also include dizziness) that means many cases go undiagnosed; According to the British Heart Foundation, almost 300,000 people are living with AF without knowing they have it. This is worrying, as the condition puts them at five times the risk of suffering a stroke.

In AF, which is the most common heart rhythm disorder, the heart beats erratically and sometimes faster or slower than normal (the usual heart rate is between 60 and 100 beats per minute, but in AF can reach 200).

The condition is caused by abnormal electrical activity in the upper chambers of the heart (the atria); As a result, these do not contract completely, so they are not synchronized with the two lower chambers. While not life-threatening on its own, AF increases the chance of blood clots forming that can travel to the brain, blocking blood flow and causing a stroke.

And the number of AF cases has increased dramatically, says Andre Ng, consultant cardiologist at Glenfield Hospital in Leicester and professor of cardiac electrophysiology at the University of Leicester.

“About 10 or 15 years ago we used to say it affected 1 or 2 percent of the population, but now it’s about 2 or 3 percent,” he says.

“One of the reasons for this is that we live longer (one in ten people over 70 have AF) and, as we age, we have more time to acquire other diseases that can trigger AF, such as diabetes and high blood pressure. , heart disease and heart failure.’

Having played professional rugby for almost 20 years, the former British Lions captain was used to pushing himself hard.

Another factor that affects people of all ages is obesity, which can cause inflammation in the heart tissue. “But I also see many younger athletes in my practice who suffer from AF,” he adds.

A review published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine in 2021 found that people under 55 who regularly engaged in “mixed and endurance sports activities” had almost two and a half times the risk of AF compared to non-athletes.

“We know that exercise is good,” says Professor Ng, “but too much exercise is not necessarily good for us, and excessive exercise, for example at a particularly competitive level and prolonged resistance training, can cause additional stress on the heart”.

This is because it raises blood pressure, “so the heart is under stress,” says Professor Ng.

“If this is done repeatedly, the additional stress can ‘stretch’ the heart cells and cause them to become excited and ‘fire’ electrically, causing extra heartbeats that trigger AF. I see a lot of enthusiastic or competitive athletes, especially long-distance runners, who suffer from atrial fibrillation early in their career.’

One of the reasons why more cases are being detected among younger people is the increasing use of “smart” watches, some of which can detect possible problems with heart rhythm, he says. AF is diagnosed with an electrocardiogram (ECG), which records the electrical activity of the heart using small sensors attached to various points on the chest and body.

Alun had a normal ECG in 2021, but the one he had last July as part of his medical checks before joining French rugby club Toulon “immediately showed that something was not right,” he says. The doctor explained to him at the time that he had AF, but that he was lucky it was detected, as it may not be detectable all the time.

Professor Ng says that once AF is diagnosed, any underlying causes will be treated, such as high blood pressure, which increases the risk of AF because it stresses the heart. Treating the cause can help better control AF symptoms. “If there is no underlying cause, we try to reduce the long-term effects of AF, which are the risk of stroke and heart failure,” he adds.

AF that comes and goes (called paroxysmal AF) can be treated with medications such as beta blockers that slow the heart rate or blood thinners to prevent clots from forming. Patients with more persistent AF may be offered cardioversion, in which an electrical shock is given to “reset” the heart rhythm.

An alternative is catheter ablation, in which a thin, flexible tube is passed through a blood vessel in the groin to the heart and the area producing the faulty rhythm is destroyed by heat or freezing.

This causes a scar in the heart that abnormal electrical activity cannot pass through. Alun was advised that cardioversion was best for him as his symptoms were persistent.

“I knew I would get my treatment once my short-term contract was up, so I went out and played, concentrating on the games,” says Alun, who joined Toulon from Swansea-based Ospreys in July 2023. ” I carried on as usual, but I was more aware of my body.

Alun played his last professional game last November: two weeks later he underwent cardioversion. “It was like being plugged into a socket, the medical team told me,” Alun says.

“After cardioversion, the symptoms (palpitations and shortness of breath) disappeared and I was not as fatigued.”

Today, he takes no medications, but uses a KardiaMobile heart monitor, which has pads that you place your fingers on to record the heart’s electrical activity in 30 seconds. The results are then sent to an app on your mobile phone.

“This team gave me peace of mind,” he says. “If I’m feeling palpitations and wondering if it’s indigestion or too much caffeine, I might take them out and use them.”

He keeps fit, for example, by swimming, running and cycling, and is grateful to have passed the medical examination in Toulon.

“I would have finished my playing career and never found out about my atrial fibrillation, which probably would have left me in a worse situation in the future,” he says. “Diagnosing them when they did, it’s a good thing for me, and now I’m making others aware of it too.”

Alun is working with AliveCor’s Let’s Talk Rhythm campaign to raise awareness about atrial fibrillation.

Vitamin Math

“Vitamin B12 helps create red and white blood cells, platelets (important for blood clotting) and DNA,” says dietitian Frankie Phillips. ‘B12 also helps maintain healthy hair, nails and skin.

We obtain it from foods of animal origin; Good sources include meat, fish, poultry, milk, eggs, fortified breakfast cereals, plant milks, and nutritional yeasts.’ Vegans may need to take a B12 supplement.

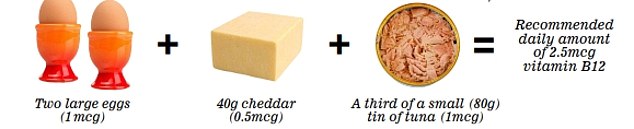

Foods that add up to the recommended daily intake of nutrients