Microplastics are invading almost every region of the globe, but these tiny particles now threaten to erase part of human history.

Researchers from the University of York in the UK have discovered the first traces of microplastics at two archaeological sites in York that have produced important finds from the Roman and Viking periods.

Microplastics, less than five millimeters long, enter our bodies through plastic packaging, some foods, tap water and even the air we breathe – and have been linked to cancer and health problems. fertility.

But foreign objects dug out of the ground in the UK could potentially compromise the preserved remains, rendering them worthless to science.

The team found more than 25,000 microplastics in the samples, which were likely the direct result of human activity, such as industry, agriculture, transportation and everyday life.

The Wellington Row site is linked to the Viking period, archaeologists have discovered tonnes of animal bones, a quarter of a million pieces of pottery and 20,000 other interesting objects.

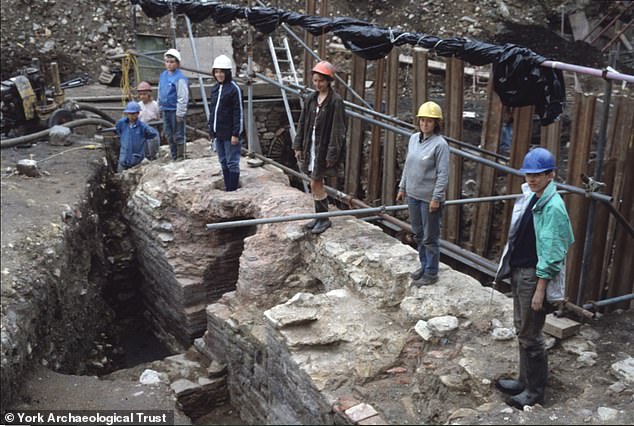

Excavations at the Roman site of the Queen’s Hotel have revealed the remains of an ancient wall, suggesting the area may have been of major importance to the ancient empire.

Microplastics have recently attracted a lot of attention due to their prevalence and abundance in our daily lives.

They have also been found in almost every region of the world, from the deepest place on earth, the Mariana Trench, to the summit of Mount Everest.

Professor John Schofield of the Department of Archeology at the University of York, said in a statement: “This seems like an important moment, confirming what we should have expected: that what were previously thought to be pristine archaeological deposits, ready for study, are in fact contaminated with plastic, and that this includes deposits sampled and stored in the late 1980s.

“We know about the presence of plastics in oceans and rivers.

“But here we see our historical heritage incorporating toxic elements.

“To what extent this contamination compromises the evidentiary value of these deposits, and their national importance, is what we will try to discover next.”

Microplastics, less than five millimeters long, enter our bodies through plastic packaging, some foods, tap water and even the air we breathe – and have been linked to cancer and fertility problems .

The team found more than 25,000 microplastics in the samples, which were likely the direct result of human activity, such as industry, agriculture, transportation and everyday life.

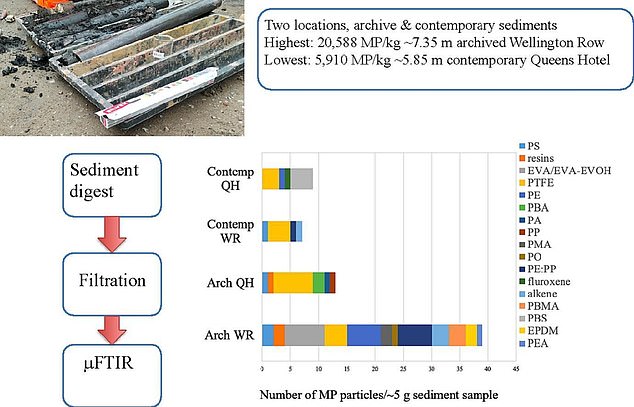

The team analyzed soil samples taken from Wellington Row in 1989 and the Queen’s Hotel in York in the same year and in 1990 – a total of three samples from each.

The earlier Wellington Row depots were revealed to date from the late 1st or early 2nd century and extended to the 19th and 20th centuries.

And those of the meeting at the Queen’s Hotel from the end of the 1st century to the 20th century.

Wellington had the highest concentration, with 20,588 microplastics per kilogram and samples from the Queen’s Hotel site contained 5,910 per kilogram.

At the site linked to the Viking period, archaeologists have discovered tons of animal bones, a quarter of a million pieces of pottery and 20,000 other interesting objects.

Excavations at the Roman site of the Queen’s Hotel have revealed the remains of an ancient wall, suggesting the area may have been of major importance to the ancient empire.

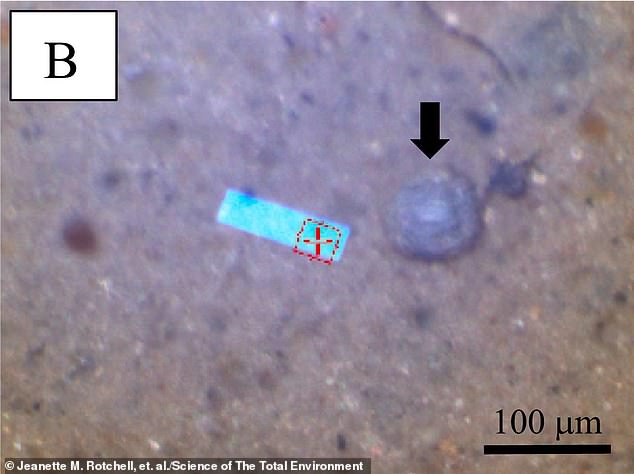

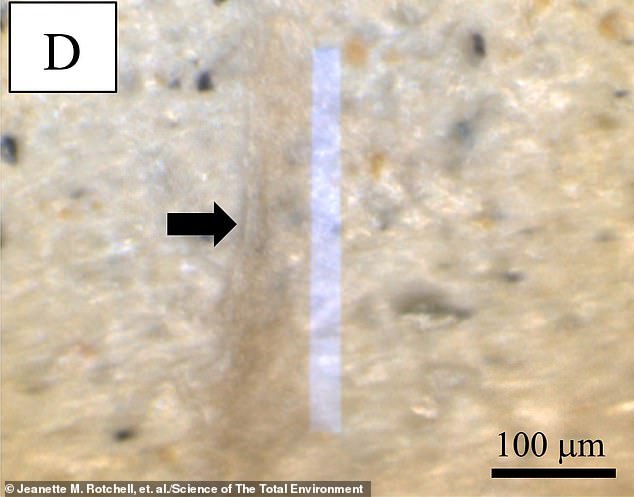

The team used a technique called Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTRI), which can identify unknown plastics in materials.

The device detected tens of thousands of microplastics in the six small soil samples – and 16 of them could not be categorized.

Plastics that could be included are ethylene-vinyl and polyalkene, which are used in food packaging.

Polyethylene, found in water bottles, polypropylene, used in pots, and hydrocarbon resin, which is added to rubbers, printing inks and adhesives – other plastics have also been discovered.

However, 57% of the microplastics found were classified as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) – or what is commonly known as Teflon, used in non-stick coated cookware.

Around 17 different microplastics were identified in soil samples

The team hypothesized that tiny particles may have been introduced to the archaeological sites during excavations in the 1980s.

“Plastic storage buckets (PP), coring tubes (polymethacrylate), as well as a one-week air sample from the archive’s storage facilities identified different types of predominant polymers compared to those characterized in archived sediments,” the researchers wrote in the study. .

The team said this work was a pilot study to see if microplastics have entered valuable sites and noted that “if replicated across the UK, many heritage assets are potentially at risk from increased deterioration and loss of information potential.

Since plastics degrade slowly, the particles could impact the chemical and physical composition of the soil.

“The potential for radiocarbon dating or residue/trace element analysis may be compromised by the presence of (microplastics), and again requires further investigation to identify whether these are real risks,” we read in the published study.

“The loss of information potential could pose the greatest threat to in situ preservation.”