- Hospitals typically charge patients only after they have been cleared to leave.

- The initial payment may have violated the law governing emergency care.

- READ MORE: Missouri hospital investigated after denying emergency abortion

<!–

<!–

<!– <!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

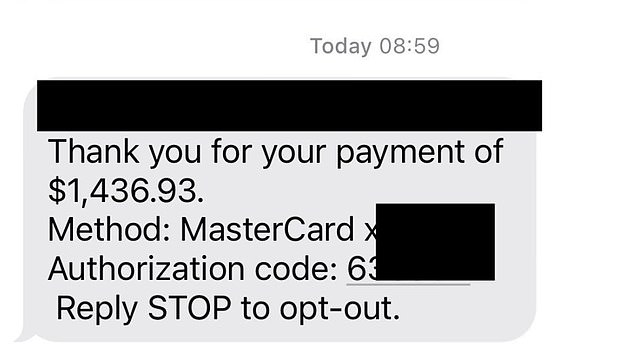

A Texas mother was shocked to discover that doctors would not operate on her son to remove his appendix until her husband shelled out more than $1,000.

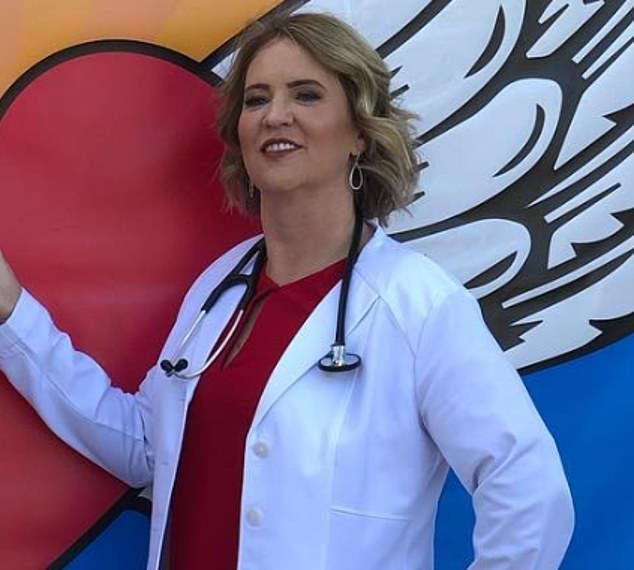

Dr. Emily Porter, a sexual health and wellness physician in Austin, Texas, saying that her second-grade son developed appendicitis overnight and had to be rushed into emergency surgery.

Even though her son was in critical condition, the hospital demanded a prepayment of $1,463.93 without offering an explanation as to how administrators arrived at that figure. Typically, Dr. Porter’s copay for emergency care is just $250.

Dr. Porter and others believe that the hospital’s demand for preventive payment is a violation of EMTALA.

This law says that anyone who comes to the emergency department must be stabilized by doctors regardless of their insurance status, and will then be billed.

Dr. Emily Porter of Austin, Texas, said her husband had no choice but to pay the hospital up front so he could give their son much-needed emergency surgery.

Dr. Porter said she believes this is a violation of a federal law that requires emergency departments to stabilize patients regardless of whether they have insurance to pay part or all of the bill.

doctor porter saying: ‘How is it possible that when you ask how much something is going to cost so you can plan/shop for prices, no one seems to know, but somehow they come up with this on the fly before the surgery is done and without a detailed explanation of the costs. benefits? ?’

She added that it was not she who took her son to the hospital, but her husband. She was given no other option and, since her son needed surgery, she did not want to delay the process any further and she paid the considerable sum.

Patients without a true emergency who come to the emergency department must pay an initial fee of $150.

However, under EMTALA or the Emergency Treatment and Labor Act, hospitals cannot demand payment before stabilizing someone in a medical emergency. And appendicitis is a medical emergency.

Dr Porter said: “At worst it looks like a violation of EMTALA and at best it is in poor taste for a parent of a seriously ill child.” I think I’ll make a fuss so it doesn’t happen to the next person.’

It is not clear which hospital Dr. Porter’s son was admitted to, but there are about 50 in the city.

Hospitals that violate EMTALA risk paying tens of thousands in fines and even losing their federal funding contracts.

Most hospitals in the country receive some amount of government funding, but some are private and not covered by EMTALA.

If Dr. Porter’s son went to a private hospital, that could explain the charge, although it is much more normal to pay after discharge.

Violation of EMTALA jeopardizes government funding.

If, in fact, the hospital is found to have violated the law, it could face financial penalties of up to $100,000 and could be exposed to a civil lawsuit.

Hospitals that violate the law could also lose their agreements with Medicare and Medicaid providers.

Last year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced it was investigating two hospitals for allegedly violating the law after they failed to provide necessary stabilizing care to a person experiencing a medical emergency.

The National Women’s Law Center filed the initial EMTALA complaint on behalf of Mylissa Farmer, Freeman Hospital West in Joplin, Missouri, and the University of Kansas Health System in Kansas City, Kansas.

The staff refused to perform a life-saving abortion at 18 weeks, despite the risk that Ms. Farmer could have contracted an infection, suffered hemorrhage and potentially died because such care would have constituted an abortion.

The Biden administration has repeatedly said that the EMTALA language includes allowances for an emergency abortion to be performed if the mother’s life is in danger. However, hospitals in many red states are hesitant to do so for fear of legal and financial penalties.