Table of Contents

Willie Mays, the iconic Hall of Fame center fielder known as the greatest baseball player of all time, died Tuesday, the San Francisco Giants announced. He was 93 years old.

Mays, nicknamed “The Say Hey Kid,” had a professional baseball career that spanned four decades, beginning with the Negro Leagues in the late 1940s and ending with the New York Mets in 1972. In between, he spent 21 years with the New York Mets. Giants, who would later move to San Francisco.

It is with great sadness that we announce that Willie Mays, San Francisco Giants legend and Hall of Famer, passed away peacefully this afternoon at the age of 93. pic.twitter.com/Qk4NySCFZQ

— SFGiants (@SFGiants) June 19, 2024

Early interest in baseball

Mays was born on May 6, 1931 in Westfield, Alabama, and was named Willie, not William. His parents were talented athletes, but his father was the one who introduced Mays to baseball. Cat Mays was a semi-pro player on several local black teams and had his son sitting on the bench with him when she was 10 after teaching her the fundamentals years earlier.

When he was in high school, Mays played several sports. His professional baseball career began in 1948, when he played for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro League before finishing high school. He signed with the Giants after graduating high school in 1950 and earned his call up to the majors in May 1951 after just one year of playing in the minors.

May’s career

Mays was a true five-tool player, excelling in speed, pitching, fielding, hitting for average and hitting for power. He had a career triple slash line of .301/.384/.557, with 660 home runs, 525 doubles and 338 stolen bases. He led the National League in stolen bases four times and led the National League in home runs four times. During 24 seasons in the majors, he hit ground balls into only 45 double plays.

In May, 10 hits were added to Mays’ career total when Negro League statistics were officially integrated into the MLB all-time record. His home run total was not adjusted due to the lack of box scores of those games.

In the grand scheme of his career, it didn’t take long for Mays to become the incredible all-around player we remember today, but it wasn’t instantaneous. He debuted on May 25, 1951, and did not put up overwhelming numbers (his first hit, a home run, came against the Boston Braves in his fourth game in the majors), but he won the Rookie of the Year award, the first of many. awards. .

He also earned the nickname “The Say Hey Kid” in his rookie year. He was given it by his manager, Leo Durocher, or New York Journal American writer Barney Kremenko, who said he gave Mays that name because the shy freshman “would blurt out, ‘Say who,’ ‘Say what,’ ‘Say where,’ ‘Say hello.'” In my newspaper, I put the tab “Say hello boy.” He got stuck.”

Mays spoke and sang accompaniment “Say Hey (The Willie Mays Song)” in 1954, recorded by the Treniers, with music legend Quincy Jones conducting the orchestra.

Mays didn’t get the chance to follow up his promising MLB debut until 1954, after serving two years in the Army during the Korean War. He spent most of that time (most of 1952 and all of 1953) playing on military baseball teams with other MLB players and traveling to entertain the troops.

When he returned home in 1954, the switch had been flipped. Mays had the best season of his career, hitting .345/.411/.667 with 41 home runs. He won MVP and was selected to the All-Star Game.

While that was his best season overall, he had many great ones after that. From 1955 to 1966, Mays finished in the top six in MVP voting in all but one year, winning MVP again in 1965 and placing second twice. He was selected to the All-Star Game 20 times in his career (24 times if you count the second All-Star Games from 1959 to 1962). He won the All-Star Game MVP in 1963 and 1968, becoming the first player to win the award twice, and also won 12 Gold Gloves.

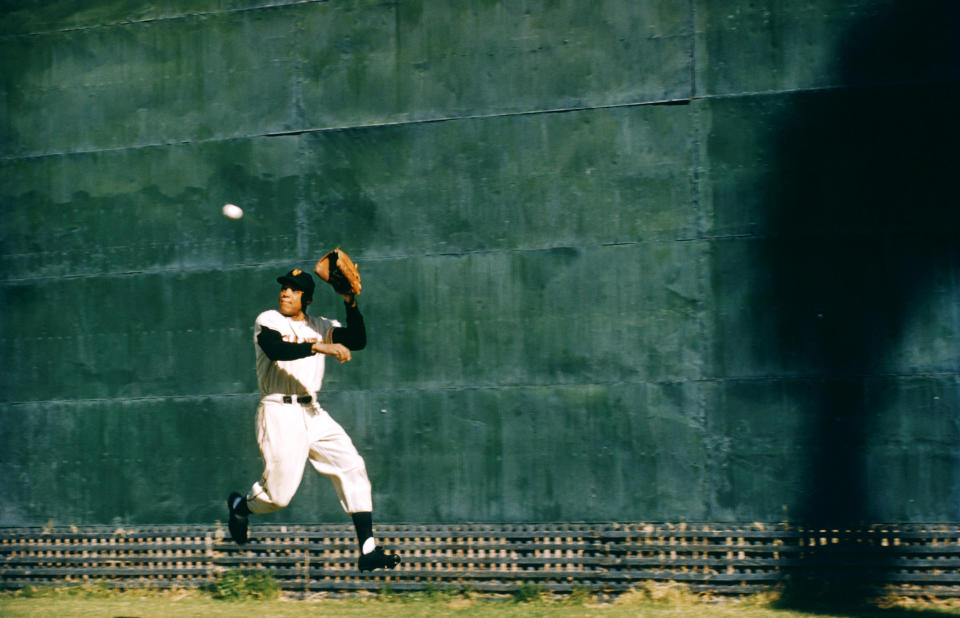

Despite his prolific hitting, Mays said he enjoyed fielding more than anything else.

“Don’t get me wrong: I like to hit.” he told the Sporting News in 1955. “But there’s nothing like going out into the outfield, running after a ball and throwing out someone trying to take that extra base. This is very funny”.

As a player, he set many on-field records, but one off-field record set an important precedent for future players. On February 20, 1963, he signed a contract with the Giants worth $100,000 a year, the first six-figure contract in baseball history.

The biggest catch ever

Despite his success on the field, Mays won only one World Series in his 24-year career, with the 1954 New York Giants, who swept the Cleveland Indians (now known as the Guardians). That series gave us one of the most iconic and greatest plays in MLB history: Mays’ famous over-the-shoulder catch.

The play, still known simply as “The Catch,” came in Game 1 at the Giants’ home stadium, the Polo Grounds. The score was 2-2 in the top of the eighth inning and the bases were loaded with Cleveland players. Cleveland’s Vic Wertz stepped up to bat and smashed a ball into the stadium’s cavernous center field. Mays, sprinting from the shallow center toward the wall, managed to track the ball and make an impressive, no-look catch. He then turned and fired a throw to second base, preventing the runners from scoring.

Mays said he didn’t evaluate his fielding plays (“I don’t compare them. I just catch them,” he said via ESPN), but “The Catch” is still considered one of the greatest of all time.

And Mays never had a doubt the ball would land in his glove.

“I had it all the way” he said.

Mays’s later life

Mays began a slow decline in the late 1960s, although he still posted a National League-best .425 OBP in 1971. The Giants traded him to the Mets in May 1972, after which he eventually returned. to play in front of the New York crowd. .

While Mays was not named an All-Star in 1972 for the first time in his career, he earned one final nod in 1973, his final season.

After retiring, he became hitting coach for the Mets until 1979, when he terminated his baseball contract to become a receptionist at an Atlantic City hotel and casino. Then-commissioner Bowie Kuhn banned Mays from playing baseball because of his connection to the game, but he was reinstated in 1985 by Peter Ueberroth, Kuhn’s successor.

The Giants, who retired Mays’ number in 1972, signed him to a lifetime contract in the 1990s, making him a permanent special assistant to the president. He spent years visiting the Giants’ minor league teams, attending spring training and making appearances on behalf of the club.

Mays is survived by his son, Michael. Mays married his wife, Mae Louise Allen Mays, in the early 1970s. She died in 2013 after a long battle with Alzheimer’s.

May’s legacy

Mays was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1979, his first year of eligibility. It was a surprise that it was not a unanimous choice. Twenty-three BBWAA members did not select him on their ballots, giving Mays 94.68% of the votes.

New York Daily News writer Dick Young was stunned.

“If Jesus Christ showed up with his old baseball glove, some wouldn’t vote for him.” young man wrote. “He dropped the cross three times, didn’t he?”

Despite those 23 votes without Mays, Mays was revered in the industry. Years after his retirement, many baseball announcers of that era still considered him the best all-around player they had ever seen.

His first manager, Leo Durocher, maintained over the years that Mays came to the majors fully formed as a legend.

“I never taught him anything” Durocher said. “He taught me. Willie is the best player I’ve ever seen in my life. I have no doubt.”

Warren Spahn, who threw the ball that became Mays’ first major league hit (a home run), he reflected on that moment years later.

“He was 0-for-21 the first time I saw him. His first major league hit was a home run against me, and I’ll never forgive myself for that. We could have gotten rid of Willie forever if I had.” He just struck him out.” (Note: Mays went 0-for-12 when he faced Spahn for the first time.)

Even celebrities understood how talented Mays was.

“I can’t stand Willie Mays” said Dodger fan Cary Grant in 1971. “Imagine, knowing when a teammate is going to hit the ball and how far, where and at what instant it will land at a certain point and being there when it does.”

Actress Tallulah Bankhead He summed it up simply: “There have only been two true geniuses in the world: Willie Mays and Willie Shakespeare.”

In 2015, Mays received the highest honor the government can bestow on a civilian: the Presidential Medal of Freedom. When President Barack Obama presented him with the award, he joined Ernie Banks, Yogi Berra and Stan Musial as the only baseball players to receive the nation’s highest civilian honor.