Table of Contents

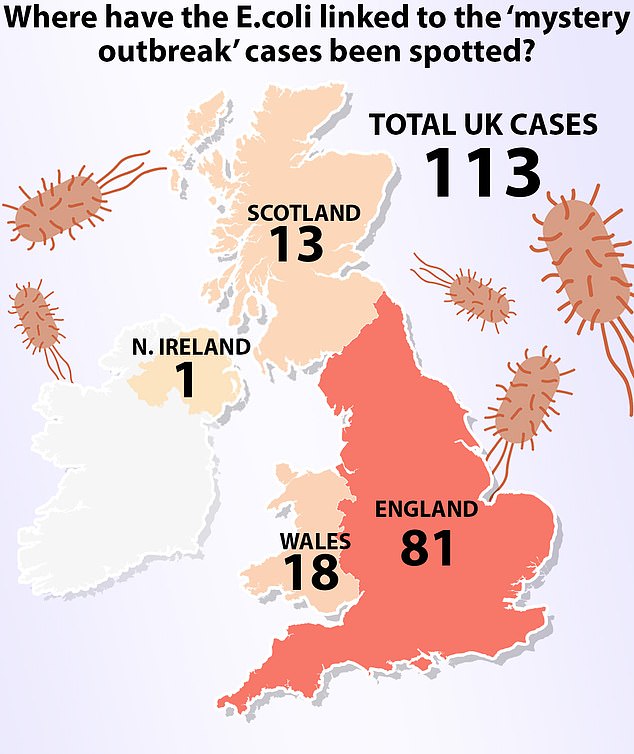

More than 100 Britons have been affected by a mysterious E. coli outbreak, with health officials still searching for the source of the infection.

Cases have been reported across the UK, and the bacteria that causes diarrhea made a significant proportion of those infected so sick that they required hospital care.

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) said it believes the cases are linked to an as-yet-unknown “nationally distributed food” or “multiple foods.”

A total of 113 cases were recorded between May 25 and June 4, but this figure is expected to increase as more cases come to light.

Here, MailOnline reveals the early warning signs of violent infection, how long they last, what foods you can catch it from and what you should do if you become infected.

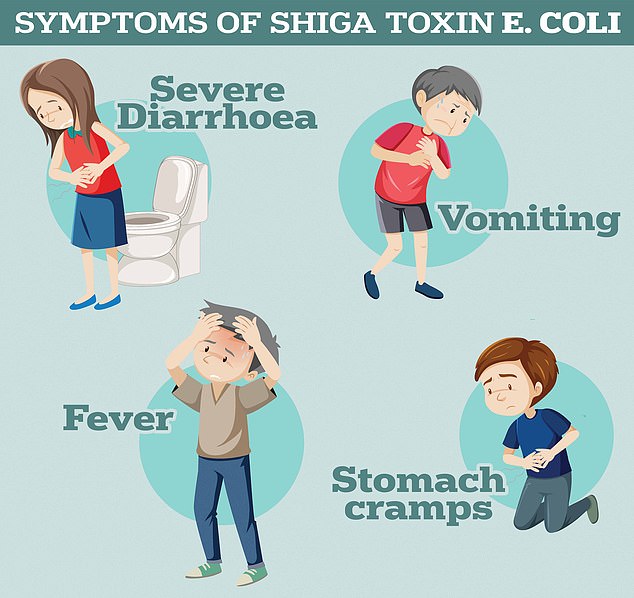

Symptoms of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli include severe diarrhea and vomiting, according to the UK Health Safety Agency.

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) said it believes the cases are linked to a “nationally distributed food” or “multiple foods”.

What are the symptoms of an E. coli infection?

The current outbreak is caused by Shiga toxin-producing E. coli 0145 (STEC).

Symptoms of the infection range from mild diarrhea to bloody diarrhea, UKHSA says, with around half of infected people experiencing the latter.

Vomiting, fever, and stomach cramps are other telltale signs of an infection.

However, these symptoms can be caused by a variety of insects, including norovirus.

In severe cases, the virus can cause hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), a life-threatening disease that can lead to kidney failure and primarily affects children.

A small proportion of adults may develop a similar condition called thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), which is a rare and life-threatening blood disorder.

Health officials have urged parents to call NHS 111 if they or their children have bloody diarrhea.

Children, the elderly, and people with compromised immune systems are at increased risk of developing serious illness.

Authorities have not yet traced the origin of the outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), a rare strain of the virus that causes diarrhea. But they believe it is related to a “nationally distributed food” or “multiple foods.”

How long does the infection last and what should I do?

Most people sick with the virus will improve without NHS care within a week, although symptoms can last up to a fortnight.

Infected people are advised to drink plenty of fluids, as symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can lead to dehydration.

Health officials say taking antibiotics or antidiarrheal medications is generally not recommended for STEC.

This is due to the potential to increase the risk of complications such as HUS, as the impact of medications on bacteria can cause a build-up of toxins.

It is recommended that anyone who experiences symptoms of STEC stay home from work or school until 48 hours after they stop vomiting or having diarrhea to reduce the risk of spreading the infection to others.

People who serve unwrapped food, are healthcare workers, or attend preschools or daycare centers are especially at risk of transmitting the infection to others.

These individuals should be tested for STEC before returning to work or school in accordance with government guidelines.

Health officials said a total of 113 cases were recorded between May 25 and June 4. Of these, 81 were in England, 18 in Wales and 13 in Scotland.

What foods can it be obtained from?

STEC is primarily transmitted by eating contaminated foods, such as raw vegetables, cheese, and undercooked, improperly washed, or prepared ground meat.

Such foods are at risk of STEC contamination, as bacteria can easily jump from contaminated work surfaces or from infected people who prepare food and have not washed their hands properly.

For that reason, it is important to properly cook ground meat, such as hamburgers, and wash all salads and vegetables thoroughly to remove any possible traces of animal faces before consuming them.

People are also advised to ensure their refrigerator is below 4°C, as this can slow the growth of bacteria.

In a previous recent E. coli outbreak, patients reported eating grated hard cheese before becoming ill.

This can happen if the milk becomes contaminated with fecal matter and survives or grows during the cheese-making processes.

Unpasteurized cheeses, where the milk used to make the dairy product is not heated to a temperature that kills bacteria, are at higher risk of contamination.

STEC can also be transmitted by directly touching infected animals or their feces, as well as by coming into direct contact with sick people, such as caring for them.

It can also be transmitted through contaminated water, either by drinking contaminated supplies or accidentally ingesting it while swimming.

This risk can be reduced by boiling drinking water that is suspected to be unsafe and not swimming in water that may be contaminated by cattle and sheep in nearby fields.