Soft drinks could act as a “gateway” to real alcohol for young people, research suggests.

Australian experts, who surveyed more than 600 teenagers, found that more than half thought alcohol-free products were appealing and more than one in three had tried them.

Some teens also told researchers they feared their peers might become “addicted” to the taste of non-alcoholic alternatives and, as a result, drink more once they turned 18.

Researchers said the results highlighted the need to treat non-alcoholic beers, wines and cocktails with caution, so that they do not act as a “Trojan horse” for young people who choose the real thing.

This comes at a time when non-alcoholic drinks have seen a boom in the UK in recent years, becoming an increasingly popular alternative to alcohol among health-conscious consumers.

Australian experts who analysed the behaviour of more than 600 teenagers who did not drink alcohol found cases of paranoia and even fear of drinking these drinks. One of them said that they could “make young people addicted to them”.

The British Beer and Pub Association, which represents the interests of pubs and breweries, said sales of low- and no-alcohol beer grew by 15 per cent in 2022, and that the sector had seen 520 per cent growth in the past decade.

Writing in the diary AppetiteAustralian researchers said the rise in popularity of these drinks should be viewed with caution.

“The present findings highlight the need to treat non-alcoholic products with a degree of caution and to devise strategies to foster their potential as a harm reduction tool, whilst ensuring that they do not negatively impact minors by acting as a Trojan horse for the industry,” they said.

‘Achieving this balance will help minimize the potential risks of these increasingly popular products.’

Julia Stafford, vice chair of Cancer Council Australia’s Nutrition, Alcohol and Physical Activity Committee, who conducted the study, added: ‘We already know that the more exposed children and young people are to alcohol advertising, the more likely they are to start drinking alcohol earlier and to drink at risky levels if they already drink alcohol.

‘Drinking alcohol at any level can increase your risk of cancer.

‘Alcohol brands claim that non-alcoholic products are aimed at adults only, yet the study found that young people often nominated their own age group as the group these products would most often appeal to.

‘There are currently no regulations limiting the ways in which alcohol products are simulated, nor restrictions on their marketing or sale, meaning that young people can buy these products and are exposed to marketing in highly visible places, such as supermarkets.

“This environment creates a public health risk for young Australians.”

In the study, researchers conducted five online focus groups with 44 Australian teenagers aged 15 to 17 to provide them with information about their experiences with non-alcoholic products.

They then surveyed 679 teenagers of the same age online to find out their opinions on alcohol-free products.

Experts found that more than a third (37 percent) of teens surveyed had tried non-alcoholic products and more than half (56 percent) said they found them appealing.

Four out of five teens also recalled seeing the products for sale.

A 15- or 16-year-old boy told researchers: “I think non-alcoholic drinks, like non-alcoholic beer, make younger people addicted to them and when they turn 18, they might start drinking beer.”

A 16-17 year old girl added: “You don’t really want kids to start enjoying and drinking the taste of alcohol, because that encourages them when they’re a bit older to drink more alcohol because they really like it.”

Another girl, also aged 16-17, said: “I think kids aged 14-15 are very easily influenced. And if they start drinking at a younger age, they’ll want to start drinking alcohol for real.”

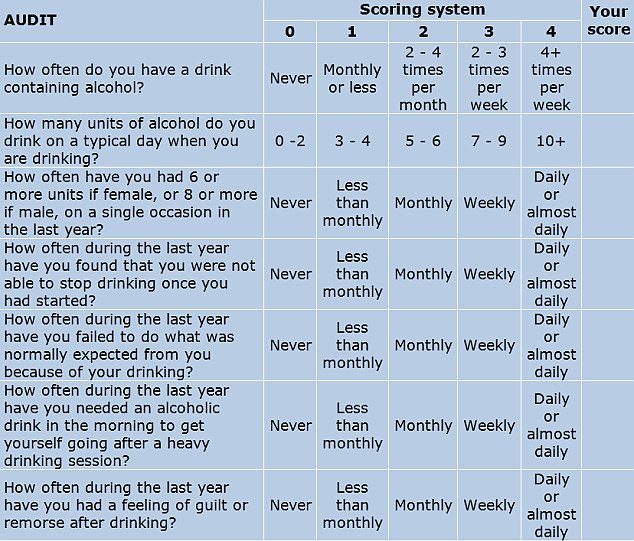

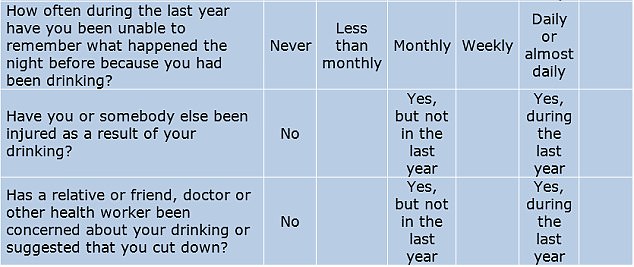

The National Health Service (NHS) recommends drinking no more than 14 “units” of alcohol (about six glasses of wine or pints of beer) a week. This recommendation has been watered down in recent decades in light of studies illustrating the health dangers of alcohol.

‘Drinking non-alcoholic beverages appears to be a gateway to drinking real alcohol.’

The researchers added that parents may also be encouraging their children to drink more in the future by sharing such beverages with them at home.

‘Drinking non-alcoholic products socially at home with parents could normalize alcohol-branded product consumption and create positive experiences around alcohol-branded product use,’ they said.

However, the authors acknowledged that the study had “several limitations,” including the exclusive use of online surveys, which could “limit the representativeness of the survey.”

They added that another limitation was that their study was based on Australian adolescents and therefore might not be applicable to other groups.

Additionally, teens who participated in the survey may not have been truthful about things like their zero- or no-alcohol drinking habits, which may have influenced the results.

Non-alcoholic alternative beverages, such as beers, wines, and mocktails, are often considered a healthy alternative for adults.

But a MailOnline audit last year found they are not always as healthy as consumers might suspect – with some low- and no-alcohol drinks containing up to ten times more sugar than their full-bodied alternatives.

In March, researchers at the University of York also said there is not yet enough data on consumer behaviour around no- or low-alcohol drinks to claim they are a healthy alternative to alcohol.

The latest data, collected by the World Health Organisation and compiled by the University of Oxford’s Our World in Data platform, shows that wine consumption in the UK has soared to 3.3 litres of pure alcohol a year (2019), up from 0.3 litres recorded almost 60 years earlier in 1961. It now accounts for more than a third (33.7 per cent) of all alcohol consumed in the country and is almost level with beer (36 per cent), which has fallen from 5.8 litres in 1961 to 3.5 litres today.

Leading experts have debated the harms of moderate alcohol consumption for decades.

The issue came to the fore last year when WHO officials warned that no amount of alcohol is safe.

However, all scientists agree that excessive alcohol consumption can permanently damage the liver, cause a variety of cancers and increase blood pressure.

The NHS recommends that people drink no more than 14 “units” of alcohol (about six glasses of wine or pints of beer) a week.

This has been diluted in recent decades in light of studies illustrating the dangers of alcohol to health.

Meanwhile, the United States says women should drink no more than seven standard drinks a week and men can have 14..

These measurements include a medium-sized glass of wine and 340 ml of beer, about the size of a normal bottle.