Scientists in Italy made headlines this week after claiming that the famous Shroud of Turin dates back to the time of Jesus, some 2,000 years ago.

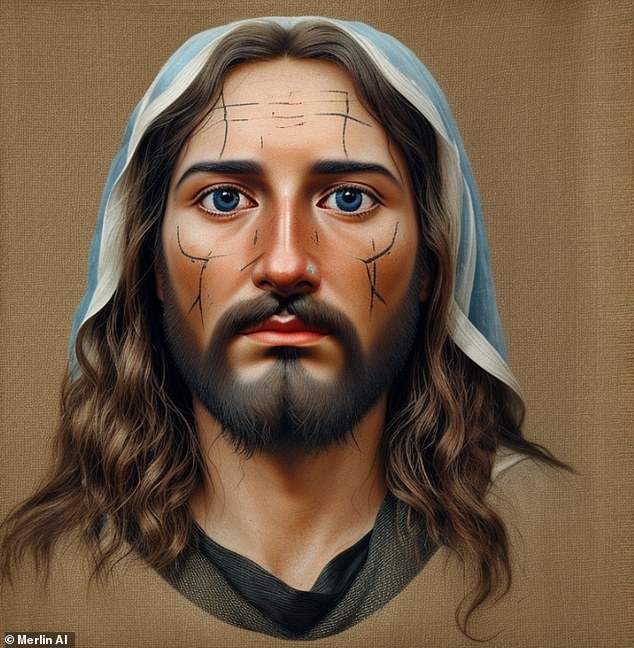

Now, an artificial intelligence has reimagined what the son of God might have really looked like based on the prized relic, which is said to feature an imprint of Jesus’ face.

MailOnline asked AI tool Merlin: “Can you generate a realistic image of Jesus Christ based on the face on the Shroud of Turin?”

The AI-generated result suggests that Christ was white, with large blue eyes, a trimmed beard and thorn marks on his face.

So can you see the similarities with the famous sacred footprint?

MailOnline used artificial intelligence to create a realistic image of Jesus Christ based on the footprint on the Shroud of Turin

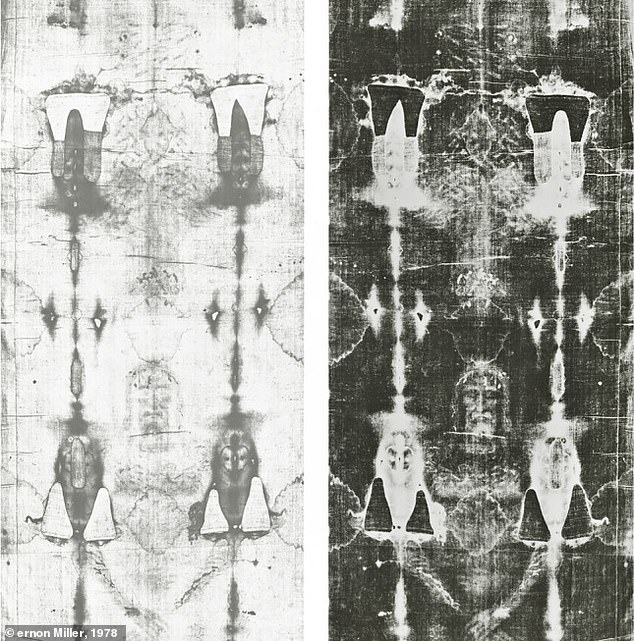

The Shroud of Turin presents the image of a man with sunken eyes, which experts have analyzed under different filters to study it (in the image)

For some historians, the Shroud of Turin, kept in a chapel in the centre of the Italian city, is one of the most sacred relics of Christianity.

“The Shroud is claimed to be the shroud that wrapped the crucified Christ when he was placed in the tomb,” said Tim Andersen, a research scientist at the Georgia Institute of Technology who was not involved in the new study.

‘There is no plausible scientific explanation for how it could have been forged or even created by natural processes.’

When first displayed in the 1350s, the Shroud of Turin was promoted as the actual shroud used to wrap Christ’s mutilated body after his crucifixion.

Also known as the Holy Shroud, it bears a faint image of the front and back of a bearded man, which many believers believe is the body of Jesus miraculously imprinted on the cloth.

Research in the 1980s appeared to debunk the idea that it was real by dating it to the Middle Ages, hundreds of years after the death of Christ.

But Italian academics have used a new X-ray technique to date the material and confirmed it was made around the time of Jesus, some 2,000 years ago.

The startling finds lend credence to the idea that a faint, bloodstained drawing of a man with his arms crossed in front of him was left next to Jesus’ dead body.

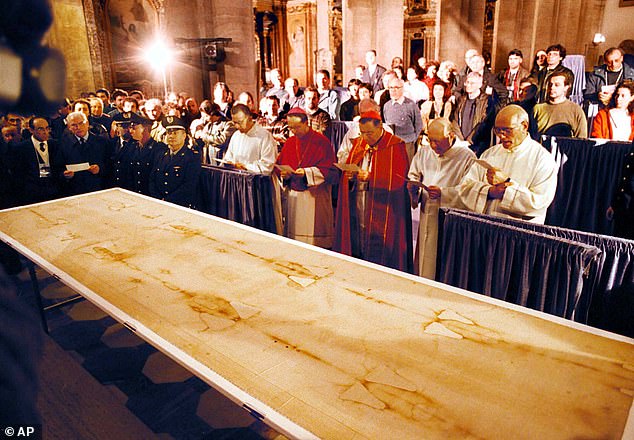

The Shroud first appeared in 1354 in France. After initially denouncing it as a fake, the Catholic Church has accepted it as authentic. Pictured, Pope Francis touches the Shroud of Turin during a visit in 2015

Many believe the Shroud of Turin (pictured) is the cloth in which Jesus’ body was wrapped after his death, but not all experts are convinced it is authentic.

The cloth appears to show faint, brown images on the front and back, depicting an emaciated man with sunken eyes who was between 1.70 and 1.80 metres tall.

The marks on the body also match the wounds from Jesus’ crucifixion mentioned in the Bible, including thorn marks on the head, lacerations on the back and bruises on the shoulders.

Historians have suggested that the cross he carried on his shoulders weighed around 300 pounds, which would have left him with bruises.

The Bible states that Jesus was whipped by the Romans, lining up the lacerations on his back, who also placed a crown of thorns on his head before the crucifixion.

The new research contradicts findings from the 1980s that indicated the shroud dates nowhere near the time of Jesus.

Some suggest that the blood stains on the shroud (shown in this negative image) are clear evidence that the cloth was used to wrap a wounded person.

The Bible states that Joseph of Arimathea wrapped Jesus’ body in a linen shroud and placed it in a new tomb.

An international team of researchers analyzed a small piece of the shroud using carbon dating and determined that the cloth appeared to have been made sometime between 1260 and 1390, during the medieval period.

However, the authors of the new study say carbon dating would not have been reliable because the fabric has been exposed to contamination over the centuries that cannot be removed.

Furthermore, as Andersen points out, there is no way to explain how it could have been forged using medieval technology.

“While authenticity cannot be established, it should be fairly easy to determine whether it is a medieval forgery,” Andersen said.

‘However, despite decades of scientific evidence and peer-reviewed articles on the subject, that conclusion has never been proven.

‘Rather, the evidence has consistently pointed in the opposite direction to any known forging technique.’