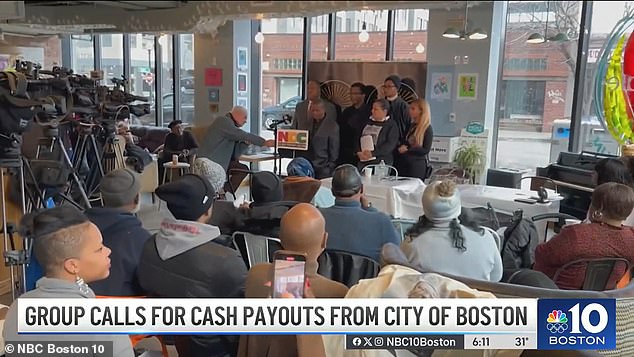

Boston activists have urged the city to allocate $15 billion in reparations to Black residents, stoking fears of a possible strain on resources amid cuts to police and veterans in this year’s budget.

The Rev. Kevin Peterson of the Boston People’s Reparations Commission launched the call this weekend, saying the city was “built on slavery” and should now “pay it forward” to black residents.

The sum includes $5 billion in direct cash payments to Black Bostonians, a $5 billion investment in new financial institutions and $5 billion to fight crime and improve schools for Black children, the agency says. commission.

Critics of the repairs say they are unfair and costly: The $15 billion is nearly four times the $4.2 billion the Boston City Council voted to cover all services last June.

Rev. Kevin Peterson says Boston officials must ‘fully commit to writing checks’ despite shift in public opinion

The self-styled Boston People’s Reparations Commission wants $5 billion to go directly into the pockets of black Bostonians

That meant cutting budgets for police and veterans, and the city’s tax revenue only appears to be declining.

But Peterson, also a founder of the New Democracy Coalition, says officials must “fully commit to writing checks” to compensate Black Bostonians as part of a broader reparations package.

“The wealth of this city was based on slavery,” Peterson said.

“The city is responsible for returning the wealth it freely extracted from other human beings who died at some point in the work of this city.”

Activists would not settle for “meaningless rhetoric about equity and diversity in the future,” he added.

The money should flow into the pockets of black residents and build “new institutions in our community,” he added.

Peterson is a prominent activist for racial justice in Massachusetts, including last year in the campaign to rename Faneuil Hall, a popular tourist site named after a wealthy merchant who owned and traded slaves.

Peterson speaks like an activist: The city created its official Reparations Task Force in 2022, which last met on February 6.

The group is working on a research paper on slavery in Boston; and is scheduled to make recommendations to Mayor Michelle Wu this summer.

Councilors only managed to pass this year’s budget by cutting funding to the police

Rev. Peterson (right) made headlines for his initiative to rename Faneuil Hall, a popular tourist site named after a wealthy merchant who owned and traded slaves.

Peterson’s request for massive payments comes at a difficult time for the national reparations movement.

Cities and counties across the country launched racial justice task forces at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests after the police killing of George Floyd in May 2020.

But attitudes have changed, and officials are withdrawing support for policies that are widely unpopular, especially among non-black taxpayers who would have to pay for them.

Last month, California’s black lawmakers backed off plans to pay $1.2 million to each resident.

They introduced a package of 14 reparations bills that made no mention of cash reparations.

Instead, they called for the state to apologize for its role in slavery, ban involuntary servitude in prisons, and return property that officials had unfairly confiscated from black families.

Like cash-strapped California, Boston would struggle to meet Peterson’s demand.

Boston’s budget for fiscal year 2024 is $4.28 billion.

City officials only kept it that low by cutting the Boston Police Department by nearly $31 million, according to the Boston Herald.

Boston Mayor Michelle Wu will receive the official task force’s repair recommendations this summer.

Morris Griffin, of Los Angeles, speaks during the public comment portion of the reparations task force meeting in Sacramento, California.

Meanwhile, the veterans office’s budget was reduced by $900,000.

Boston will lose more than $1 billion in tax revenue over the next five years thanks to falling market values of office buildings in the wake of the pandemic, Tufts University researchers warned this month.

Reparations supporters say it is time for the United States to pay its black residents for the injustices of the historic transatlantic slave trade, Jim Crow segregation and inequalities that persist to this day.

From there, it gets complicated.

There is no agreed-upon framework for what a plan would look like. Ideas range from cash payments to scholarships, land donations, business start-up loans, housing grants or statues and street names.

Critics say payments to select black people will inevitably stoke divisions between winners and losers, and raise questions about why American Indians and others don’t receive their own subsidies.

While they are popular among black Americans, other groups that would foot the tax bill are less interested.

Tatishe Nteta, director of the University of Massachusetts Amherst Poll, says support for reparations has plummeted from its peak of support among 38 percent of voters after Floyd’s killing.

“Support for a federal reparations program is down 4 percent among all Americans,” Nteta said.

“Democrats, liberals and African Americans have shown sharp declines in their level of support for the program since 2021.”

Reparations advocates in New York, California, Massachusetts and elsewhere “may no longer have a rising tide of public support for reparations behind them,” he said this month.