In the 1980s, scientists made the startling discovery that human pollution had torn a hole in the Earth’s protective ozone layer.

Now, nearly 40 years later, scientists from the Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service (CAMS) have discovered promising signs of recovery.

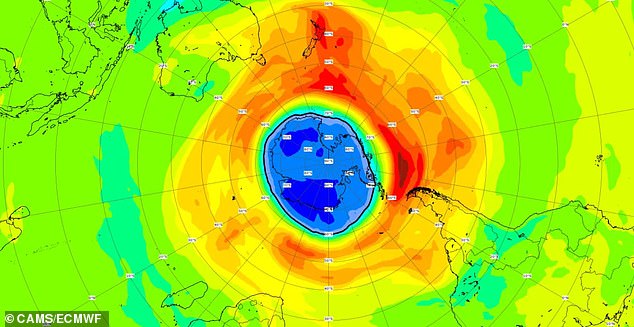

The latest atmospheric observations reveal that the ozone hole over the South Pole took longer to form and was smaller than expected this year.

As of September 13, the ozone hole was 18.48 million square kilometers (7.13 million square miles) smaller than in the same period in recent years.

Although scientists warn that this change is largely due to global weather patterns, there is still hope that the ozone layer can fully recover within the next four decades.

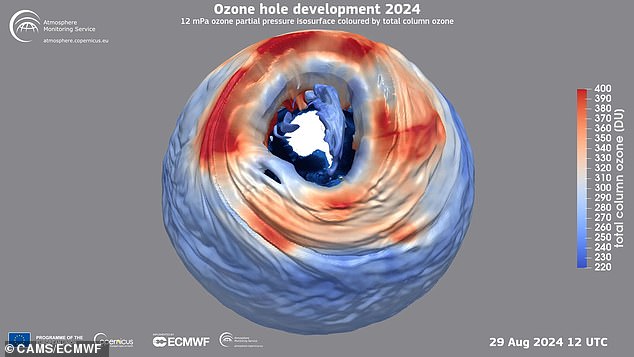

New data shows that the hole in the ozone layer over the South Pole (pictured) has taken longer to form than in previous years

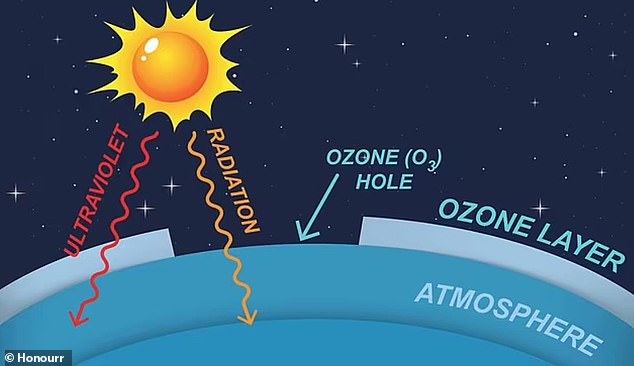

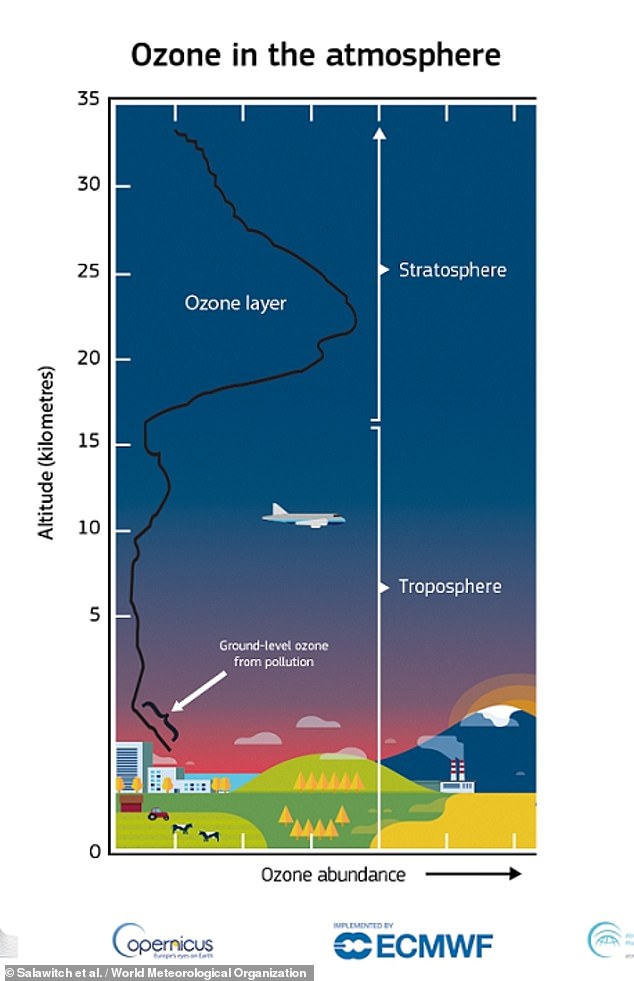

The ozone layer is a thin layer of naturally occurring ozone gas (a molecule made up of three oxygen atoms) that absorbs almost all of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation.

At ground level, this gas can cause health problems for vulnerable people suffering from lung diseases such as asthma.

However, when it accumulates in the upper atmosphere, ozone absorbs UV-B radiation that would otherwise impact Earth.

In 1985, research by the British Antarctic Survey discovered that a huge hole had formed in the ozone layer over the South Pole.

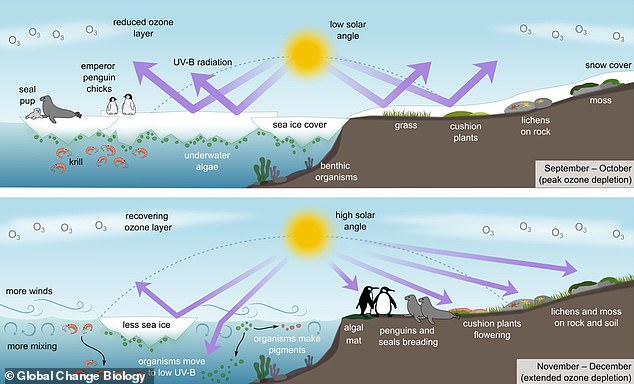

Each year, as spring approaches in the Southern Hemisphere, the hole opens again, allowing ultraviolet radiation to fall on the Antarctic continent.

This flood of radiation is so strong that Antarctic wildlife such as seals and penguins are at increased risk of sunburn.

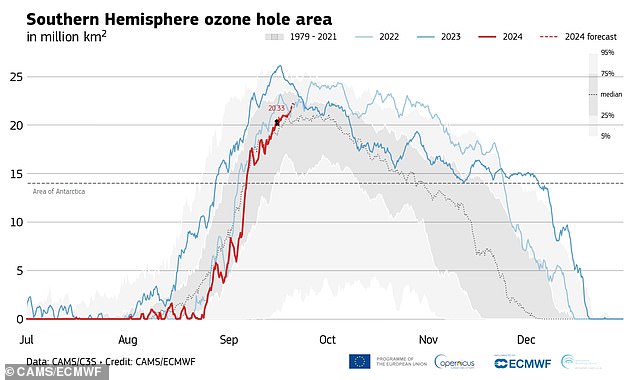

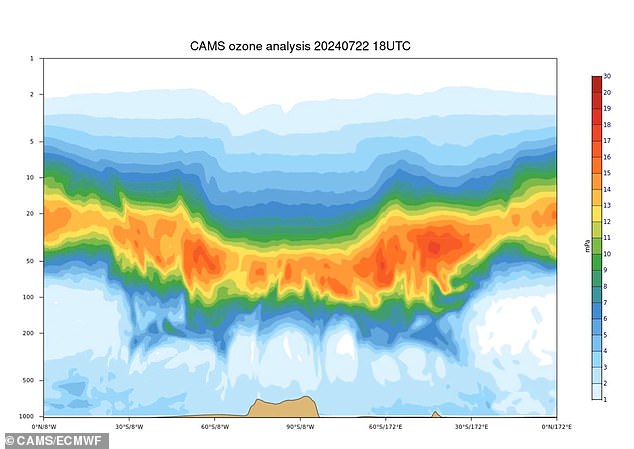

Every year, the ozone hole forms around August. This graph shows how in 2024 (red) the ozone hole has formed later and has reached a smaller extent than in previous years.

The ozone layer is vital because it prevents harmful UV-B radiation from reaching the Antarctic continent and harming wildlife there, and further warms melting sea ice (file image)

The hole is usually well established by mid to late August and closes by late November as part of an annual cycle.

But this year, new data shows that the formation of the ozone hole has been significantly slower and less dramatic than in previous years.

It wasn’t until almost September that the ozone hole began to form and it has remained significantly smaller since then.

For the rest of the year, CAMS predicts the ozone hole will also begin to shrink more rapidly and could have closed completely by early December.

The ozone layer is measured using a metric called Dobson units, which refer to the amount of ozone in a column of air extending from the ground into space.

A Dobson unit is the number of ozone molecules required to form a layer 0.01 millimeters thick at 0 °C (32 °F) sea level.

Ozone that accumulates in the stratosphere normally absorbs almost all of the radiation coming from the sun.

This year, CAMS data have revealed that most of the Antarctic region has remained above 220 Dobson units, the threshold used to define an ozone hole.

This is in stark contrast to 2023, when the ozone hole peaked at 26 million square kilometers (10 million square miles) on September 10.

Laurence Rouil, director of CAMS, explains: ‘From volcanoes to climate change, there are a large number of factors that play a role, directly or indirectly, in the formation of the Antarctic ozone hole.

‘However, none of them have as much impact as anthropogenic substances that deplete the ozone layer.’

Man-made compounds called CFCs, or chlorofluorocarbons, used in aerosol sprays and refrigerators, were responsible for depleting huge amounts of the planet’s ozone.

Although the use of CFCs was banned by the Montreal Protocol of 1987, the damage had already been done.

Previous studies have found that the delayed recovery of the ozone hole (November-December, below) means more ultraviolet radiation reaches Antarctica and during the peak breeding season for many birds, mammals and marine plants.

The ozone layer is depleted by chemical reactions, driven by solar energy, involving byproducts of man-made chemicals. This diagram shows how the thickness of the ozone layer changes with altitude.

During winter, circular winds called the Polar Vortex concentrate the remaining CFCs and ozone-depleting substances in a small area over the South Pole.

In August, when spring begins in the southern hemisphere, solar radiation and low temperatures cause these substances to erode a hole in the ozone layer.

But while the ban on CFCs has prevented the ozone hole from getting worse, experts don’t believe this year’s slower formation is necessarily a sign of recovery.

Rather, this is likely due to a disruption of the polar vortex caused by natural changes in temperature and wind patterns.

In June, Antarctica experienced two rare “sudden stratospheric warming events” that caused temperatures in the upper atmosphere to rise by 15ºC (59ºF) and 17ºC (63ºF) respectively.

In September of this year, the ozone hole (pictured in blue) was 18.48 million square kilometers (7.13 million square miles) smaller than it was in the same period in recent years.

This year’s thicker ozone layer (shown in orange and red) is largely due to a weakening of the polar vortex that concentrates ozone-depleting compounds over Antarctica.

Those spikes stretched the polar vortex into a tall, thin column that didn’t produce the fast winds that normally erode the ozone layer.

In a blog post, CAMS wrote: “Just as a period of cooler than usual weather does not reveal long-term climate trends, a slow onset of an ozone hole cannot automatically be attributed to a recovery of the ozone layer.”

But while this is not a definitive sign that the ozone layer is recovering, experts remain hopeful.

Mr Rouil says: ‘The Montreal Protocol and subsequent amendments have created enough space for the ozone layer to begin to heal, and we can expect to see further signs of recovery over the next forty years.

‘This demonstrates how humanity is capable, through international cooperation and science-based decision-making, of transforming our impact on the planet’s atmosphere.’