Scientists announced Friday that they have discovered the fossilized remains of a 240-million-year-old aquatic reptile called the “Chinese dragon.”

The ancient creature was named for its elongated, snake-like appearance, as well as the fact that the Scottish team behind the discovery found it in China.

Although the fossilized skeleton was found curled up, measurements indicated the creature was probably about five meters long, or 16.4 feet from nose to tail.

But his bones were not the only ones in the paleontological find.

Well-preserved fish bones were also found in the stomach region, suggesting that it was an aquatic predator.

Scientists have named the prehistoric creature Dinocephalosaurus orientalis. The first name means ‘terrible-headed lizard’ and the second part refers to the fact that it was found in East Asia.

The creature, whose scientific name is Dinocephalosaurus orientalis, He had an extraordinarily long neck.

The scientists counted a whopping 32 separate neck vertebrae bones.

Nick Fraser, head of natural sciences at National Museums Scotland, told BBC News that the specimen is “a very strange animal.”

For comparison, most mammals have only seven vertebrae in their necks, and even the famous long-necked brachiosaurus dinosaur had only 13.

This unique anatomy made the animal’s neck longer than its body and tail combined.

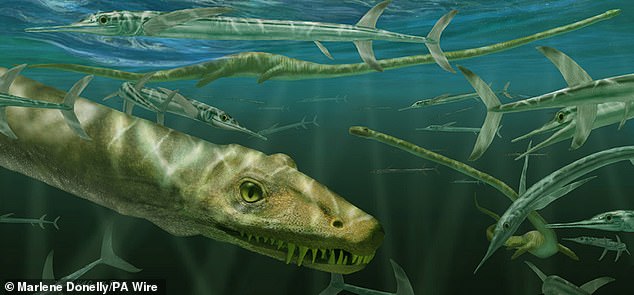

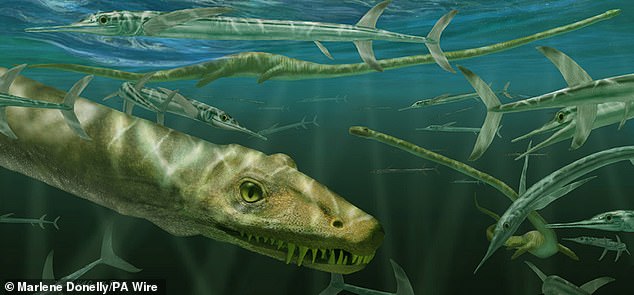

With its long neck, Dinocephalosaur orientalis makes a comparison with another strange marine reptile called Tanystropheus hydroidesthe scientists said.

This prehistoric beast lived at the same time, the Middle Triassic, in modern-day Europe and China.

“Both reptiles were of similar size and had several skull features in common, including a fish-trap-like dentition,” according to a statement. ‘However, dinocephalosaur It is unique because it has many more vertebrae in both the neck and torso, which gives the animal a much more snake-like appearance.’

Scientists suspect that the Chinese dragon was a stealthy hunter. Previous evidence suggests that the reptile gave birth alive, unlike most reptiles.

The Chinese dragon was originally identified in 2003, but it was not until now that scientists witnessed its true length, as several fewer vertebrae were found in that initial excavation.

In addition to the long neck and belly full of fish, D. orientalis It also seemed to have fins.

Scientists suspect it was a stealthy hunter, sneaking up on its prey before snatching it with a mouth full of sharp teeth.

Although it bears a strong resemblance to the long-necked pleisiosaurs that lived about 40 million years later and served as inspiration for the Loch Ness Monster, scientists said it was actually not closely related.

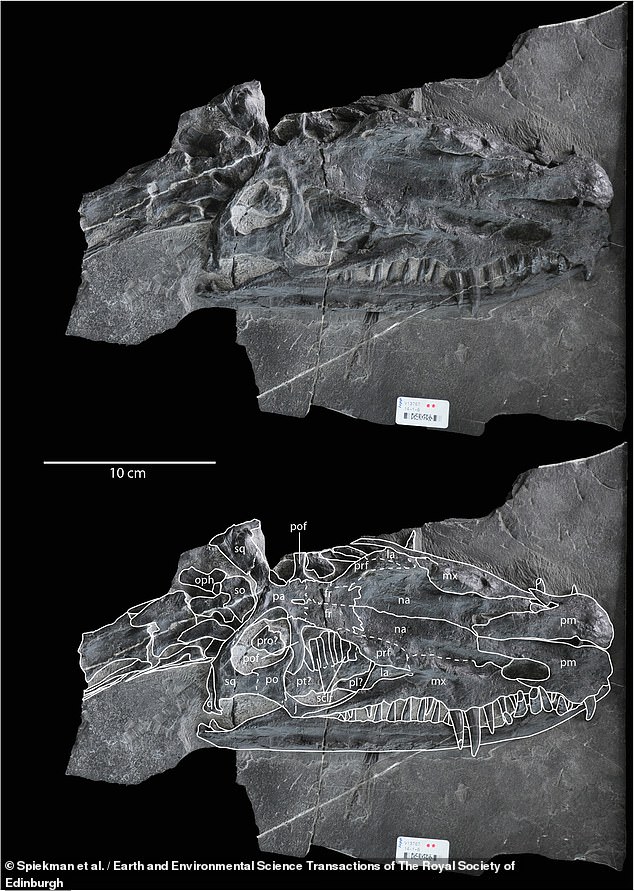

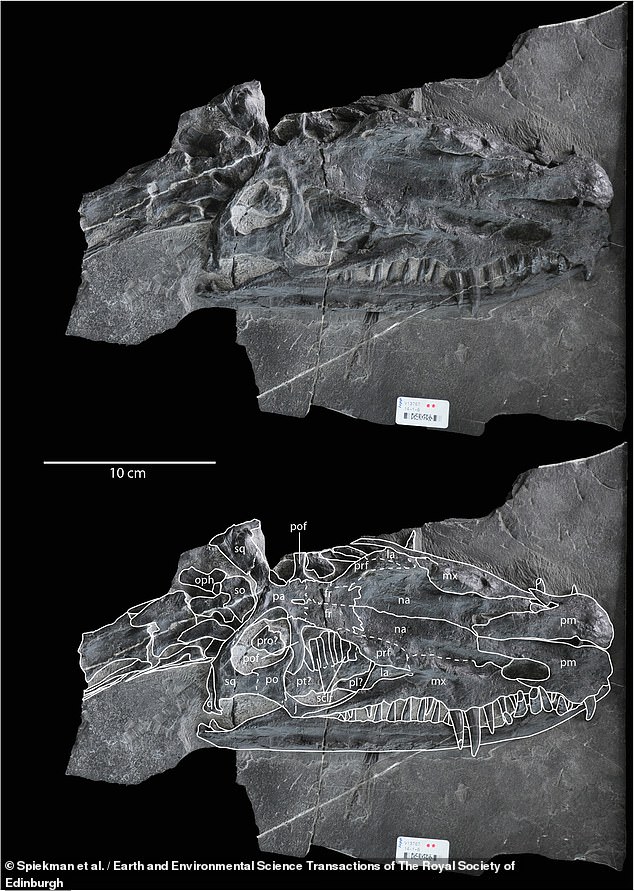

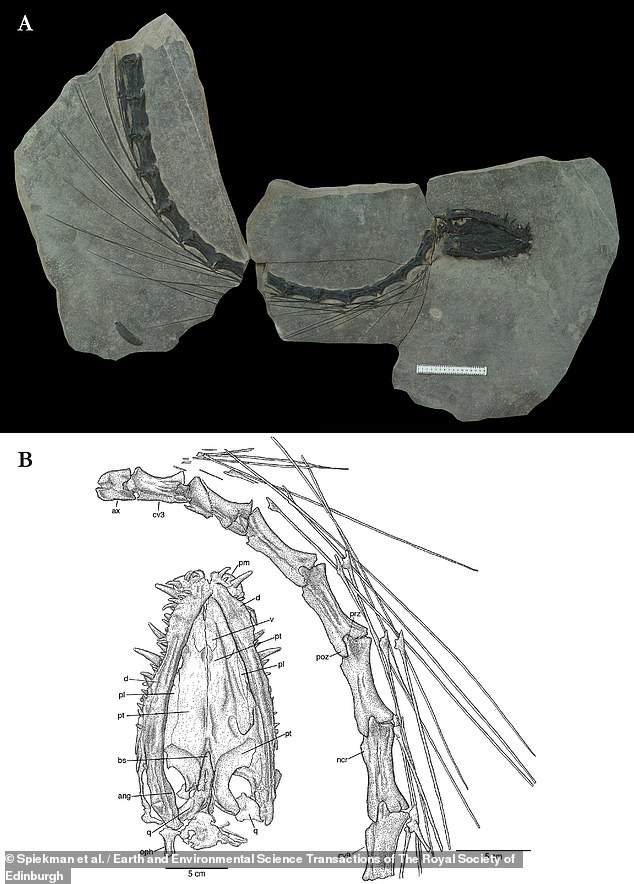

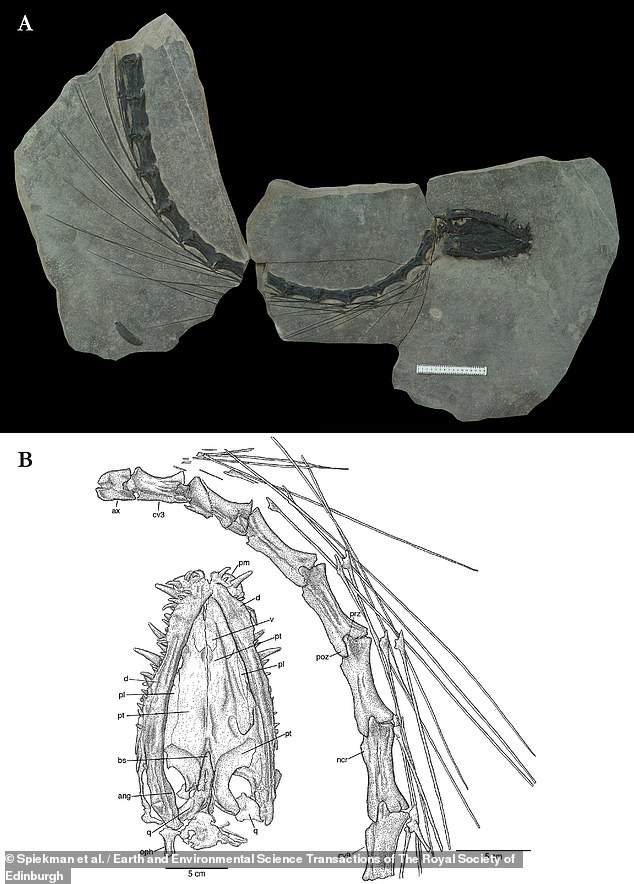

This is the holotype of Dinocephalosaurus orientalis, a well-preserved specimen that shows its features so clearly that other identifications can be made from it. The animal’s sharp teeth, which extend beyond its jaw, were clearly adept at catching prey.

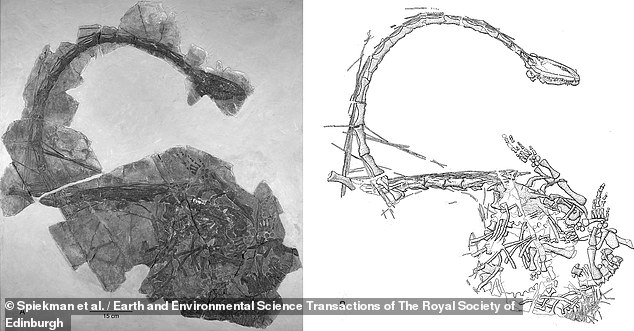

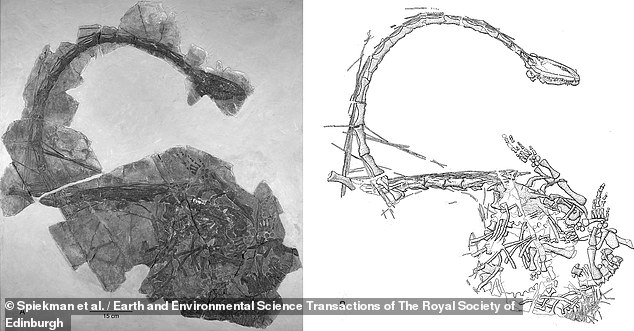

The well-preserved remains of Dinocephalosaurus orientalis show its long neck, complete with 32 vertebrae. The neck of this aquatic reptile was longer than its tail and body combined.

“This discovery allows us to see this remarkable long-necked animal in its entirety for the first time,” Nick Fraser, curator of natural sciences at National Museums Scotland, said in a statement. statement.

«It is one more example of the strange and wonderful world of the Triassic that continues to baffle paleontologists.

“We are sure it will capture everyone’s imagination due to its striking appearance, reminiscent of the mythical long, snake-like Chinese dragon.”

A fascinating feature of this animal that has already captured the imagination is the fact that it appeared to give birth alive.

In 2017, Chinese scientists discovered a fossil of this same species with another entire individual intact inside its ribcage.

Another view of the remains of the ‘Chinese dragon’ shows its extraordinarily long neck, which scientists suspect it used to sneak up on its prey without them detecting the movement of its fins.

A close-up of the animal’s fins shows that it was at home in the water. Despite being a reptile and breathing air, this species, like sea turtles, lived in water.

Her head was facing forward, which meant she wasn’t being eaten; Most predators eat their prey head-on so they fall more easily.

This discovery turned what scientists knew about reptiles upside down, providing previously unavailable evidence about the reproductive biology of the animal group.

For the new discovery, an international team from Scotland, Germany, China and the United States had studied the fossil for a decade before announcing its recommendationswhich were published today in Transactions on Earth and Environmental Sciences of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

The find highlights how rich the fossil evidence is in China, Fraser told the BBC.

“And every time we look in these warehouses, we find something new.”