Pennsylvania could be at the center of America’s new “white gold rush” with the discovery of a major untapped source of lithium in the state.

Government scientists have shown they can filter the precious metal from the state’s shale gas wastewater: extracting tons of lithium per day, leaving very little behind.

They concluded that Pennsylvania alone could produce nearly half of the United States’ total lithium demand (as of the first year), supplying this key compound needed to power everything from smartphones to electric vehicles and solar panels.

A project of this scale could turn Pennsylvania into a Saudi industrial belt, ending American dependence on lithium from China, which now controls 90 percent of the market.

And unlike many new lithium extraction proposals, which have threatened scarce water resources from Arkansas to Colorado, this process would take advantage of the high-pressure water already used in hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, of natural gas.

With 72 lithium mines proposed across the United States, the discovery could help reduce local ecological consequences as the United States moves away from fossil fuels that emit “greenhouse gases.”

More than 1,200 tons of lithium a year could be recovered from Pennsylvania natural gas fracking wastewater alone, according to new research, conducted in collaboration with the US National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL). ) and the University of Pittsburgh.

“Oil and gas wastewater is a growing problem,” as one government geochemist behind the new study put it. “We are looking for a beneficial use of that waste.”

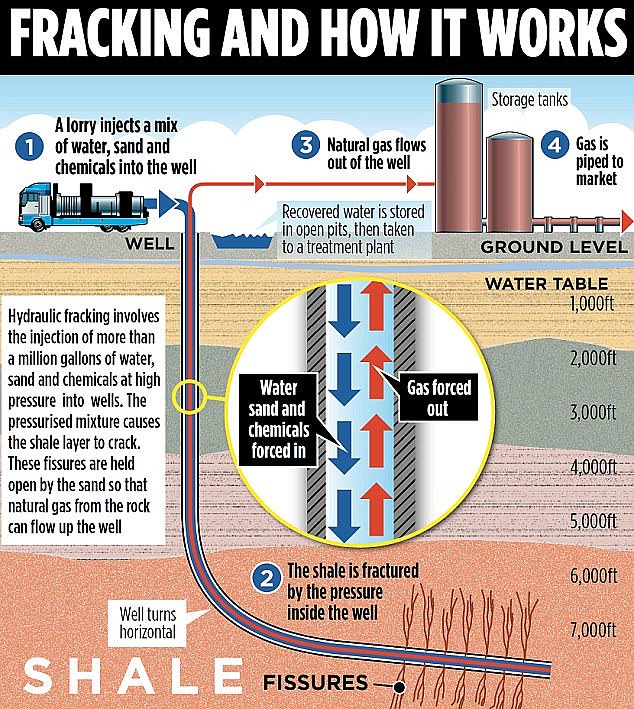

Fracking is a process used to extract natural gas from deep underground shale rocks by injecting more than a million gallons of water, sand and chemicals at high pressure into drilled wells.

The pressurized mixture opens up the shale rock, creating new fissures that the sand holds open, allowing natural gas from the rock to flow into the well.

However, despite having reduced American dependence on foreign oil, fracking has proven highly controversial due to its use of chemicals, groundwater contamination, noise, air pollution and even its ability to create earthquakes. similar to earthquakes.

And these risks have become a hotly debated topic in Pennsylvania, where fracking has been linked to cancer and other health problems.

According to new research, produced in collaboration by the US National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) and the University of Pittsburgh, more than 1,200 tons of lithium per year could be recovered from fracking wastewater alone. Pennsylvania.

Although the price of lithium has fluctuated in this new volatile market, the annual return to the state from this wastewater lithium could range between $1.6 million and $18 million at current prices.

Fracking is the process of drilling into the earth before inserting a high-pressure water mixture to release natural gas. High-pressure water, sand and chemicals are injected into underground wells to open cracks in the rock and release trapped natural gas.

Although the price of lithium has fluctuated in this new, volatile market, the annual return to the state could range between $1.6 million and $18 million at current prices.

Even more promising is that its projection that this wastewater recycling could meet nearly half of America’s lithium demand doesn’t take into account any nearby activity in other states.

The so-called Marcellus shale region, where an estimated 144 trillion cubic feet of natural gas is trapped between two huge layers of limestone, covers much of Pennsylvania but also extends into New York, Ohio and West Virginia.

“Pennsylvania has the strongest data source on the Marcellus shale,” NETL geochemist Justin Mackey he said in a statement. “But there’s also a lot of activity in West Virginia.”

Mackey and his colleagues were able to calculate the likely amount of lithium floating in solution in this fracking wastewater through contaminant reports that every oil and gas company in Pennsylvania must file with regulators.

“Lithium is one of the reportable substances,” Mackie said. “This is how we were able to carry out this regional analysis.”

According to their estimates, published this April in the magazine Scientific ReportsFracking wells in the southwestern part of Pennsylvania appear to contain nearly twice as much lithium as wells in other parts of the “Keystone State.”

Geochemist Justin Mackey and his colleagues were able to calculate the likely amount of lithium floating in solution in this fracking wastewater through contaminant reports that every oil and gas company in Pennsylvania must file with regulators.

While geologists had long known that lithium was present in the mineral content around these shale gas deposits, an accurate estimate only became feasible as years of these mandatory reports were published.

“Not enough measurements had been made to quantify the resource,” Mackey explained. “We just didn’t know how much was there.”

But there had been an accidental benefit, because lithium-based mineral compounds, such as lithium chloride and lithium carbonate, are soluble in water.

Simply injecting high-pressure water into fracking wells has managed to extract much of that lithium metal from the rock and into the fracking wastewater.

Water in underground aquifers, as Mackey said, has been “dissolving rocks for hundreds of millions of years.”

“Basically, the water has been removing the subsoil,” he said.

The United States has around eight million metric tons of lithium on its territory, meaning the US industry is worth around $232 billion.

However, the nation only accounts for about one percent of global lithium production, while China has dominated the market for decades because 90 percent of the mined metal is refined in its nation.

But reckless exploitation of America’s lithium wealth could come at a serious cost, experts warn.

About 40 of the 72 proposed lithium mines in the United States are located in Nevada, the driest state in the United States, and 80 percent of them would be located on water supplies considered at risk of low water levels, according to an analysis from the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism.

Central Nevada Regional Water Authority Executive Director Jeff Fontaine told Howard Center researchers that excessive water use in the basin can cause “permanent” damage underground and “a combination of things happening that would prevent for that aquifer to really be restored.

Poor planning for these types of mines, the Howard Center noted, could harm local communities and wildlife that need access to fresh water from these aquifers.

Patrick Donnelly, a conservation biologist at the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity, told the Howard Center that if the proposed 72 mines are built under current rules, “it would be a fundamental transformation of the American West.”

“People compare it to the gold rush, but the gold rush was pretty small scale, compared to what all this lithium looks like,” Donnelly said.