Competition took centre stage in the men’s 100m freestyle final at the 1924 Summer Olympics, then, as now, held in Paris. A century ago, swimming epitomised the Roaring Twenties. It was an era of fast music, fast cars and fast swimmers. Yet while the battle for bragging rights in the pool was tougher than ever, it was also taking place on more equal terms: for the first time, elite swimmers of different races were given the spotlight in an Olympic final, a challenge to the popular pseudoscience of the age of eugenics and widespread Anti-immigrant sentiment in the United StatesA new book, Three Kings: Race, Class, and the Barrier-Breaking Rivals Who Launched the Modern Olympic Age by Todd Balf, revisits the 1924 100m freestyle final as we look ahead to the 2024 edition this week.

“I think the interest was partly due to these three swimmers of different skin colors who really wanted to be the fastest in the most important event, the 100 meters,” Balf says of his motivation for writing the book. “I was researching these guys. The press was describing them almost as if they were superheroes: mermen, flying fish, torpedoes.”

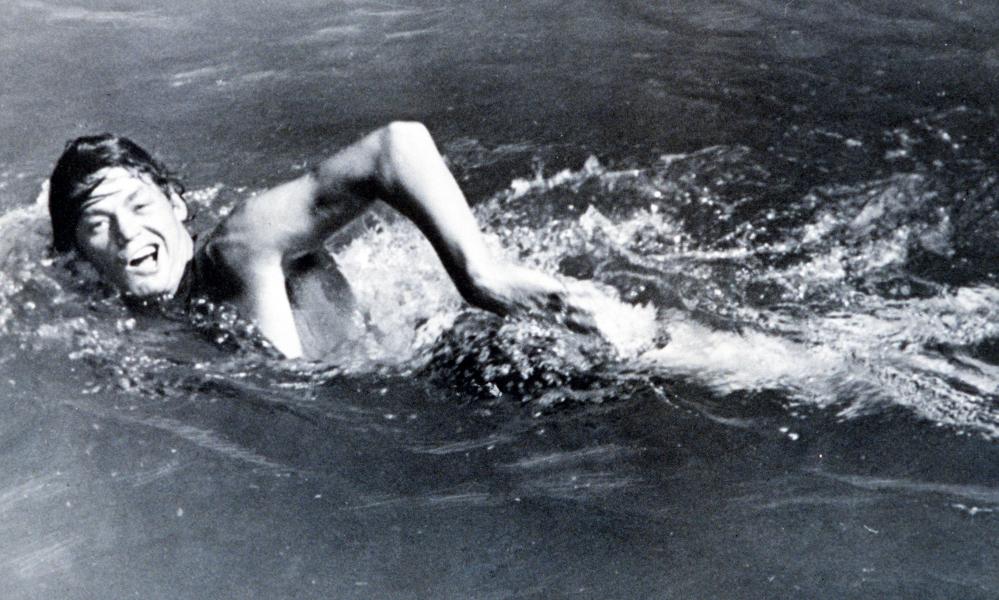

The three kings of the book’s title were Americans Johnny Weissmuller and Duke Kahanamoku, and Japanese Katsuo Takaishi.

Before starring as Tarzan on screen (his first appearance in the role came in 2032), Weissmuller was a Chicago-based snooker sensation who rose from a working-class background to break record after record. The man whose records he often broke was Hawaiian legend Kahanamoku, who faced racial prejudice in his quest to compete at the highest levels of the sport. Takaishi also faced disparaging assessments, particularly in relation to his physique, which was judged inferior to the contemporary Western ideal.

The book examines the background of each athlete, paying attention to the broader historical events that shaped their lives. Weissmuller, originally Johann Weissmuller, was born to German-speaking parents in the Austro-Hungarian Empire; they emigrated to the US due to tough economic times. Kahanamoku came of age during the American takeover of Hawaii. The Hawaiian language had been banned in schools. In 1896, Japan became an independent state and whites-only swimming clubs began to emerge. Takaishi grew up in a Japan that was debating how it should interact with the rest of the world, including whether to discard swimming styles developed in the samurai era in favor of Western techniques that offered a better chance of success at the Olympics.

The story came to Balf’s attention through his renewed interest in swimming. A decade ago, he was diagnosed with cancer. After post-operative complications, he lost the ability to walk. Accustomed to an active lifestyle, he sought out new ways to exercise while in a rehabilitation hospital in Massachusetts. When it was suggested that he swim, he initially dismissed it—he recounted an ill-fated attempt at open-water swimming for Yankee magazine in which he had to be rescued. Then he learned of the existence of a wetsuit that allowed him to swim in the hospital pool. From there, he became curious about the origin of the strokes he practiced, especially the crawl, now synonymous with freestyle.

“I read a lot of stuff,” he says. “In the course of that process, I came across the story of samurai swimmers, Hawaiian champions, and the person we would know today as Tarzan – the three main characters in the book. After meeting them, I was hooked and tried to understand who they were and where they came from.”

Kahanamoku was the first. How determined was he to compete in swimming? Unable to join segregated clubs, he and his friends formed their own: Hui Nalu, “Wave Club.” After a rocky start at the 1912 Olympic trials, he competed at the Stockholm Games that year, beginning a streak of three Olympics and five medals. The story of the famous swimmer and surfer left a deep impression on Balf, who spent a lot of time in Hawaii researching Kahanamoku and interviewing big-wave surfers. “Duke remains a legend in Hawaii,” Balf says.

As the 1924 Games approached, Kahanamoku had to face a rival nearly half his age: Weissmuller, who had had a difficult childhood in Chicago. His father had deserted the family, abandoning Johnny, his younger brother, Peter, and his mother. Weissmuller found refuge at the Illinois Athletic Club, where he caught the eye of coach Bill Bachrach, who also had an eye for the many records that could be set in swimming and how they could be used for publicity purposes. Weissmuller became Bachrach’s star pupil.

In Japan, another teacher-student relationship was yielding positive results. Takaishi grew up as an heir to Centuries-old swimming strokes In the past, they were used in warfare, but when Japanese athletes used these styles at the 1920 Olympics in Belgium, they became a laughing stock. It took Osaka-based coach Den Sugimoto to study the Western techniques and teach them to his students, including Takaishi. Sugimoto even got the students to build their own swimming pool and fill it with water from nearby farmland.

Each of the three contenders came to the 1924 Games with question marks. Japan was recovering from the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923that killed more than 100,000 people and left the country wondering whether it would field a team for Paris. Kahanamoku was at a professional crossroads and faced disappointing expectations at the U.S. Olympic trials, which were held in Indianapolis, the same venue as this year’s. As for Weissmuller, he faced a 1920s version of a “birther” controversy — an inquiry into whether he was an American citizen. The question of his citizenship was raised because of his overseas birthplace, but Balf suggests his family altered his baptismal records to indicate he was born in the United States, securing his place on the Olympic team. The secret lay dormant for years.

“You can imagine how afraid he was that he would be discovered and that everything he had gained in Paris would be taken away from him,” says Balf.

The Games themselves were mired in uncertainty. Were they a serious sporting event featuring the world’s best athletes every four years or a mere spectacle? As Balf explains, the noble vision of their modern founder, Pierre de Coubertin, often collided with embarrassing realities. Athletes had to swim in icy open water at the first modern Games in Greece in 1896; the 1900 edition in St Louis included a racist event. Mocking the athletic ability of indigenous culturesAnd the 1920 Olympics were held in a Belgium still recovering from World War I, not far from battlefields littered with corpses. By 1924, however, the Olympics were moving closer to professionalism in Paris. The City of Light had a brand new swimming stadium, the Piscine des Tourelles, which still exists today. The pool featured marked lanes and the venue could seat more than 10,000 people. In another first for swimming, the men’s 100m freestyle final would be broadcast live.

“Swimming was kind of the unexpected star of the Games,” Balf says. “I don’t think it was recognized as much as it should have been. Swimming really stole the show.”

Weissmuller went on to win the 100m sprint final in an Olympic record time of 59.0 seconds. In total, she won three golds (she also won the 400m freestyle and the 4x200m freestyle relay) and one bronze that year. Kahanamoku won silver and her brother Sam won bronze.

Kahanamoku finished fifth, had minor roles in nearly 30 Hollywood films and helped popularize his other great sport, surfing. Takaishi’s Olympic career was just beginning and he won a silver and a bronze at the 1928 Amsterdam Games, paving the way for further success for Japanese swimming at the Olympics.

“These three men, who had very different cultural upbringings, were very different,” Balf says. “You wouldn’t even think that these guys had much in common with each other. What they had in common was swimming.”

“I really wanted to know what the three of them thought of each other. In some ways, swimming trumped everything that separated them.”