It’s a growing problem for developed countries: how do we get people to have more babies?

A shock study today reveals that three in four countries could face the threat of “underpopulation” by 2050 due to falling birth rates.

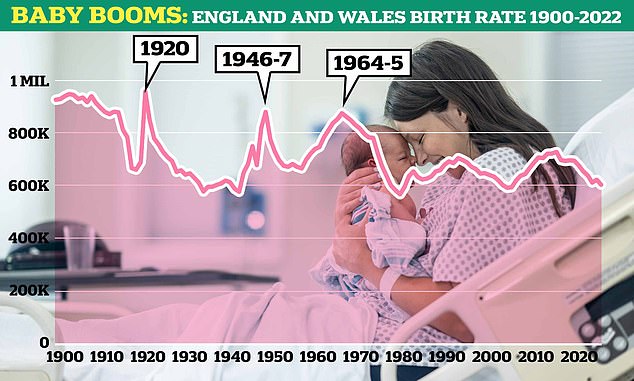

There were 605,479 live births in England and Wales in 2022, a decrease of 3.1% from 2021 and the lowest number since 2002.

This meant that the overall birth rate in 2022 was only 1.49 children per woman. And according to the National Statistics Office (ONS), women born in 1975 had an average of only 1.92 children.

This figure is quite comparable to the average of 2.08 children that women born in 1949 (their mother’s generation) had. The best year for babies in Britain was 1920, with 957,782 live births in England and Wales.

Experts attribute this situation to the economic recovery that followed the First World War. This followed a dramatic fall in the birth rate following the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918. There was a similar baby boom in England in 1946-47, after the Second World War.

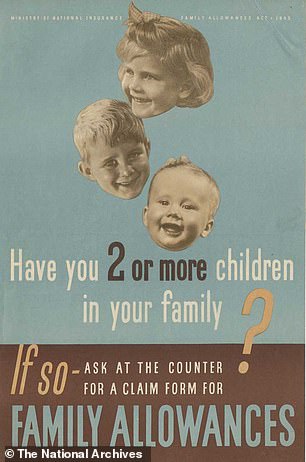

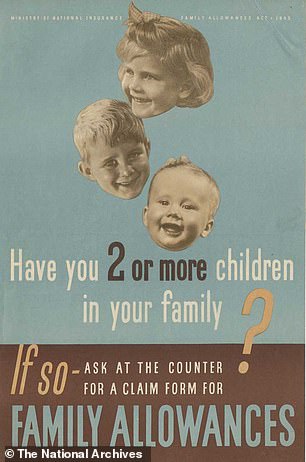

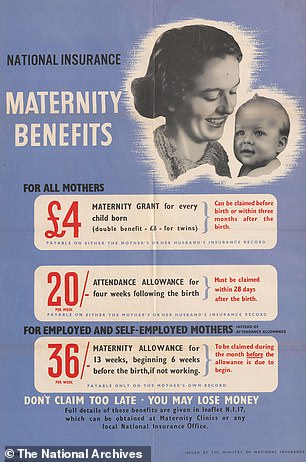

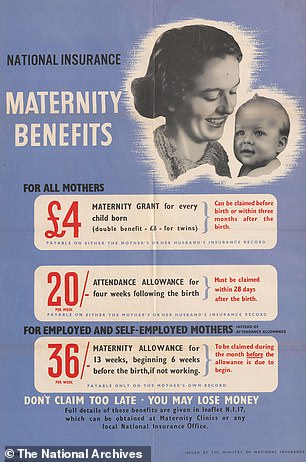

Posters from the time show how parents were offered a maternity allowance of £4 for each child, with a “double benefit” for twins.

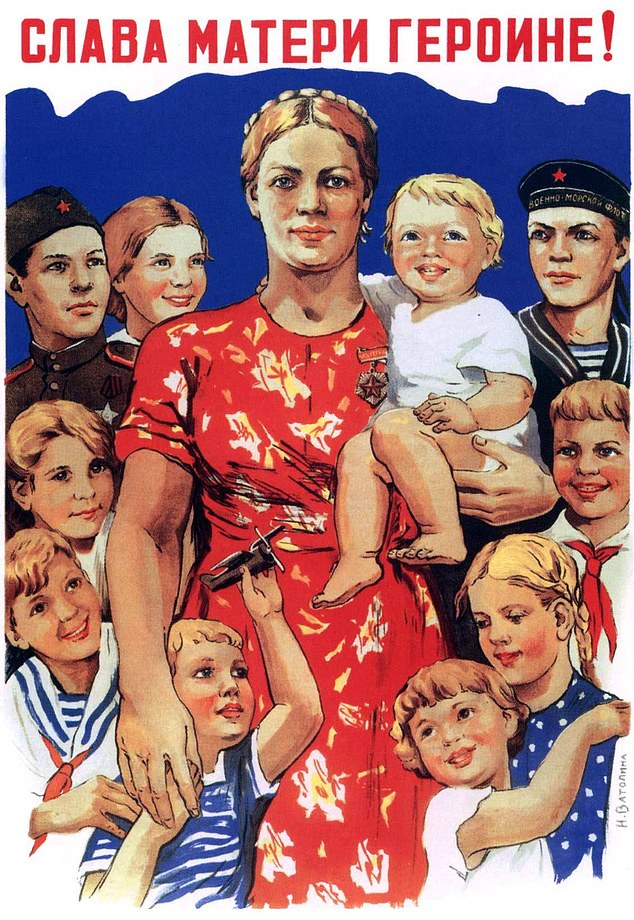

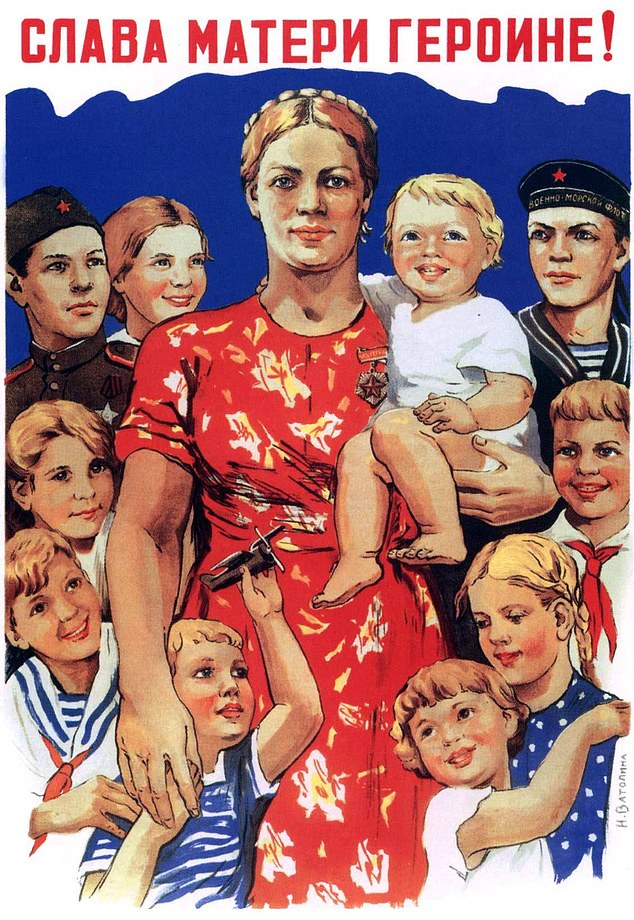

Other countries around the world have adopted radical campaigns to spur lower birth rates. In the post-war Soviet Union, Stalin’s regime issued colorful posters depicting mothers of ten children.

There were baby boomers in Britain in 1920, 1946-1947 and 1964-1965. 1920 remains the best year on record for births in England and Wales

Government posters issued in 1945 and 1946 encouraging parents to sign up for maternity benefits

In Japan, which has been in a decades-long population crisis, one city has bucked the trend by adopting family-friendly policies, increasing the birth rate from 1.4 to 2.8 children per woman in recent years.

In Singapore, in 2012, the government partnered with mint brand Mentos to encourage couples to attempt to “birth a nation” on August 9, the country’s national holiday.

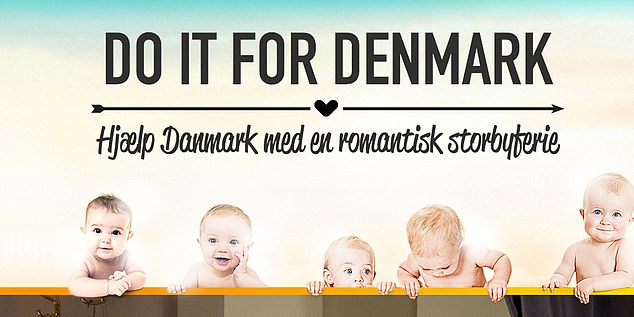

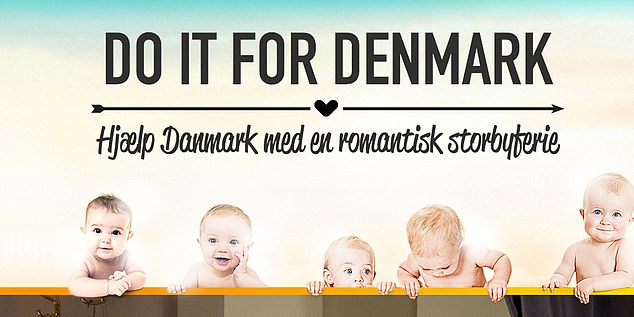

And in Denmark, a national “Do it for Denmark” campaign helped increase the birth rate.

Today’s figures for the UK are well below the 2.1 children needed to maintain the population without immigration.

For decades, demographers believed that the Spanish flu pandemic caused a baby bust in 1918 and 1919 (when there were 662,661 and 692,438 births, respectively).

However, a study published last year by the University of Oxford found that the 1920 baby boom in six European countries was due to the economic recovery after the First World War, rather than the psychological effects following the pandemic.

In Denmark, a national “Do it for Denmark” campaign helped increase the birth rate

In Singapore in 2012, the government partnered with mint brand Mentos to encourage couples to attempt to “birth a nation” on August 9, the country’s national holiday.

In America, there were an average of 4.24 million new babies born each year between 1946 and 1964. Posters issued by the government during the war advertised “freedom from want” and showed happy families around the dinner table.

In the UK as a whole, there were probably more than 1.1 million babies alive. This figure is much higher than in 1947, the post-World War II boom year, when just over 881,000 babies were born.

Much like the United Kingdom, the United States experienced a spectacular baby boom after World War II, but it lasted much longer than in Britain.

While the birth rate in England and Wales rose from just under 680,000 in 1945 to 881,000 in 1947, it then declined sharply until 1956, when it rose again to a peak of nearly 876,000 in 1964 before a further decline.

In the United States, there were an average of 4.24 million new babies born each year between 1946 and 1964.

The increase in births was attributed to the strong postwar economy, which gave Americans the confidence they needed to provide for more children.

Posters issued by the government during the war advertised “freedom from want” and showed happy families around the dinner table.

They helped promote the ideal of domestic and family life in the post-war period.

In 2020, South Korea’s fertility rate fell to just 0.84 children per woman, meaning the country has the lowest birth rate in the world.

The country’s government has offered free childcare, housing subsidies and IVF support in a bid to increase the birth rate.

A nurse looks after babies in a nursery in Britain in the 1920s

A woman pushing her baby in a specially adapted pram attached to her bicycle in Brixton, south London, 1926

Japan has been experiencing a similar crisis for decades. The number of babies born in the country fell last year for the eighth year in a row.

In 2023, 758,631 babies were born, a decrease of 5.1% from the previous year.

This is the lowest number of births in Japan since the country began compiling statistics in 1899.

One of the main reasons for the decline in births is the decline in the marriage rate. There were 489,281 marriages last year, a decrease of 5.9 percent from the previous year.

It’s the first time in 90 years that Japan’s marriage rate has fallen below half a million.

Surveys show that young Japanese are reluctant to marry or start a family because of bleak job prospects, high costs of living and corporate cultures incompatible with having both parents working.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida called the low birth rate “the biggest crisis facing Japan.”

The country’s government has tried to encourage more births with measures such as subsidies for children and more support for families.

Babies are seen in hospital cribs in the United States in the 1950s

Fifty years ago, Japan’s birth rate peaked at around 2.1 million and has been falling ever since.

As a result, Japan’s population of around 125 million is expected to decline by around 30 percent to 87 million by 2070. Four in ten people will be aged 65 or older.

However, one Japanese city is bucking the trend. In nine years, it has doubled its birth rate – from 1.4 to 2.8 children per woman in nine years – thanks to a vast program of family-friendly policies.

Families receive birth grants and family allowances and it costs half the national average to send a child to daycare.

In Hungary, women benefit from tax reductions if they have more children.

Poland’s Family 500+ program offers parents a tax-free benefit of around £100 for their second child and any other children they have thereafter.

In Sweden, every preschool child is entitled to childcare from the age of one, while in Norway the maximum price for preschool is just 3,050 crowns (£226 ) per month.