Learning a new sport is difficult. Creating one… well, that’s a completely different challenge.

Despite being one of the most popular sports in the world, basketball has not always been accessible to people with blindness and low vision.

In Frankston, Victoria, a team of low vision athletes and support workers are changing that.

Tanya Thomas, program support officer for the Frankston and District Basketball Association, began to consider the idea of organizing basketball sessions for the visually impaired after realizing that the club’s All Abilities Program was not aimed at people with blindness and low vision.

However, it quickly became clear that this was a problem that did not only affect his club.

Surprisingly, he couldn’t find any version of the sport designed for the visually impaired anywhere in the world.

“We were finding regular competitions that may have a blind athlete [playing in them]but there were no modifications for that person,” Thomas said.

Thomas, who has no experience living with low vision, knew that input from people with that experience would be vital to getting the idea off the ground.

This contribution came from members of the local table tennis club for the visually impaired.

“We literally sat around the round table and had our discussion. It was almost textbook,” Thomas said.

feel it

Brad Hoare was present at those first meetings and has been instrumental in the development of the program.

Although he was only diagnosed with legal blindness in 2018, his eyesight had begun to deteriorate much earlier.

Having played on sighted teams on both sides of his diagnosis, he was in the perfect position to guide the creation of the sport and help mentor participants who had never played basketball before.

“I walk on the basketball court and feel at home,” Hoare said.

“YO [also] “I still have enough vision to see the three-point line, the half-court line… and all those positions on the court.”

However, Hoare and Thomas knew that this would not be the case for many of the participants.

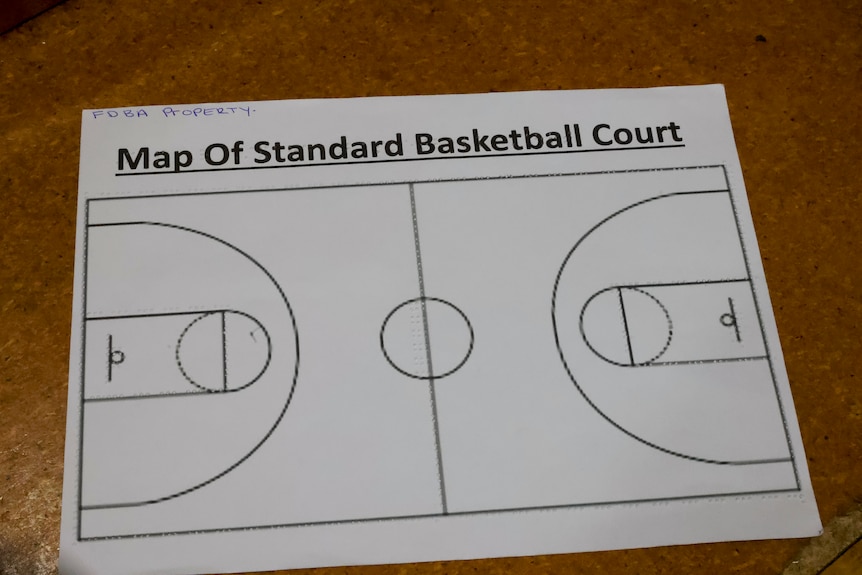

Early in the process, they developed a braille map that players could use to familiarize themselves with the court.

They also brought a retractable ring and a net for the participants to feel.

Daniel is another participant whose vision has deteriorated dramatically in recent years.

Although he still has a certain degree of nearsightedness, he has difficulty seeing things more than a couple of meters away from him.

Before participating in the visually impaired program, Daniel had never played any type of basketball.

Understandably, the combination of learning a new sport and mentally mapping your surroundings was a challenge.

“It took me a couple of weeks to get used to it, that’s for sure,” Daniel said.

Daniel is just in the process of learning braille, so the braille map was not as helpful to him as it was to some of the other participants.

But instead of limiting himself to just half the court, he used different methods to familiarize himself with his surroundings.

learning code

At the beginning of the sessions, participants walk forward from the baseline to the center of the court, following Thomas’ voice and counting how many steps they take to get there.

“That way, when we move later, if we’re standing at half court, we can know that if we take 10 steps, then we’ll be close to the key or we’ll be closer to the ring. So there’s a lot to remember involved. “Thomas said.

Along with constant mental arithmetic, sound is vital for players to map the court.

A Bluetooth speaker is connected to the network and the sound of an alarm clock is constantly played from it during shooting exercises.

While defending, players wear wristbands so attacking players can hear where they are.

The ball also has bells inside, however it only rings when rotated. Because of this, only bouncing passes are allowed.

Players are constantly communicating with each other, calling for passes, and letting other players know exactly where the ball is going.

As a result of these “keywords”, participants not only know where the ball is at all times, but they also interact with their teammates.

By implementing these visual and auditory aids, Thomas hopes the sport will accommodate people with all types of visual impairments.

“Having this all the same for everyone across the board — having to make the bounce passes, having to use the code words — makes it a lot easier and a lot more fun,” Thomas said.

In the months since the program officially began, Hoare and Thomas have seen tangible improvements in both the composition of the game and the skills of the participants.

“I’m finding it’s a big learning curve,” Hoare said.

“We’re trying things; they may not work, but we stick with them or try to adjust them.”

In the future, there will be large-scale games and tournaments on the horizon, but exactly what they will look like remains to be seen.

Hoare believes the only way to achieve this is to continue working with different ideas from players across the visual spectrum.

“People can make assumptions about what people with low vision or no vision can or cannot do. But that’s not something that anyone else should be in charge of; only the visually impaired person should be able to decide.”

Henry Hanson is a journalist and content producer passionate about telling stories about inclusion and sport.