In 1992, Pepsi held a competition in the Philippines called “Number Fever”. It ended up killing five people.

The idea was simple: numbers would be printed on the caps of soft drink bottles and each evening the local news would announce the winners.

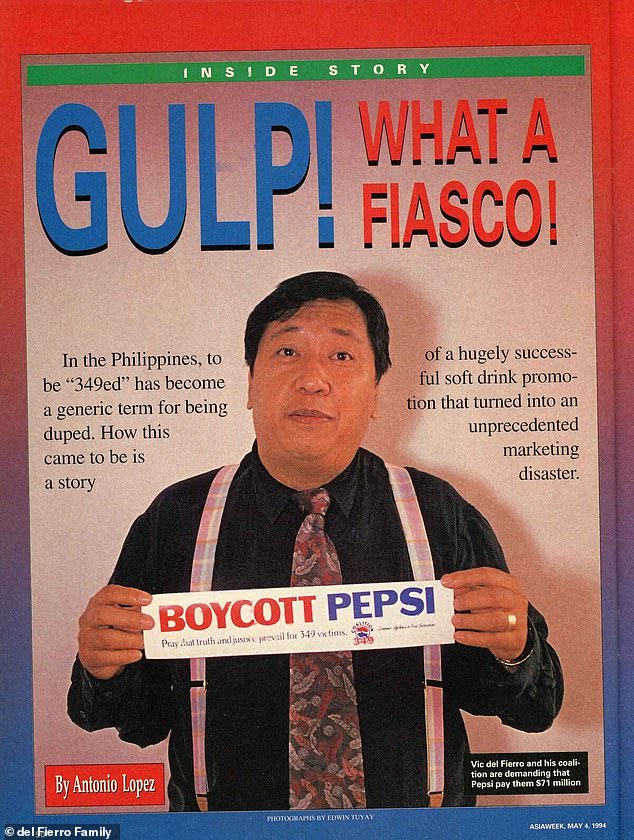

But things quickly went wrong, so much so that many Filipinos who experienced “numbers fever” are still traumatized today. These days, just the mention of the weeks-long contest can elicit a negative response.

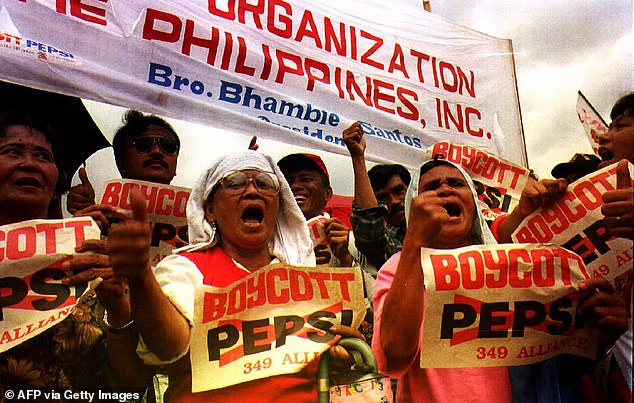

Indeed, across the Philippines’ 7,641 islands, advertisements promised Pepsi drinkers that they could “become a millionaire” by purchasing a bottle with a winning number – a wish they ultimately reneged on when a malfunction saw the winning number 349 printed on thousands of bottles. caps, instead of just two.

This meant that instead of two grand prize winners, there were now hundreds of thousands, each claiming the million pesos they had been promised.

Scroll down for video:

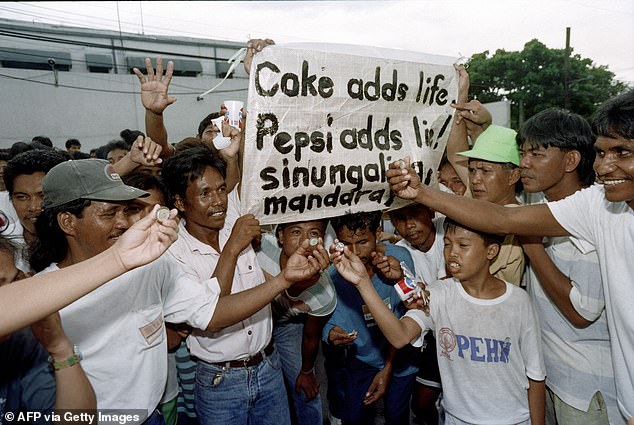

A Pepsi-Cola delivery truck driver in Manila tries to put out the fire under his truck after it was set ablaze by protesters in September 1993. Such demonstrations were common that year, after an incident involving a new promotion.

The contest, called “Number Fever,” consisted of numbers printed on the caps of soft drink bottles and each evening the local news announced the winners. However, after a computer malfunction caused the numbers to get mixed up, thousands of grand prize winners were named.

The sum today was equivalent to about $68,000, or 611 times the average monthly salary. When Pepsi refused to pay, riots broke out and a teacher and a 5-year-old child died when a grenade thrown at a Pepsi truck exploded on a crowded street.

At least three other people died and Pepsi ended up getting off with a slap on the wrist. It all started when Pepsi, sated by some success, decided to extend Number Fever for five weeks – and things only went downhill from there.

The saga began almost 32 years ago to the day, when Pepsi launched its ill-fated overseas promotion in February 1992.

The move follows a successful rollout in the US that created eight millionaires, each of whom beat odds of 28.8 million to 1 to secure a winning bottle cap.

These winners were featured in real-as-day commercials.

The ensuing fervor – and increased sales – led then-CEO Christopher Sinclair to decide to hold the competition in the Pacific, where competitor Coca-Cola reigned supreme.

Pepsi Philippines (PCPPI) then announced that numbers ranging from 001 to 999 would be printed inside the caps of Pepsi, 7-Up, Mountain Dew and Mirinda bottles.

Most daily prices were modest – around 100 pesos – the equivalent of around US$5.

But the prospect of a possible million enticed people to play, and the competition, originally scheduled to end on May 8, boosted sales so much that it was extended until the following month.

However, things would have gone wrong long before then – as Filipinos frantically bought bottles and searched for misplaced corks, often rummaging through trash cans to do so.

Then, on May 25, came a big moment: the grand prize winning cap was revealed, with the winning number being 349. That’s also when things went horribly wrong.

The contest ended up leaving five people dead, as people took to the streets to demand what they considered their rightful claim.

The sum today was equivalent to about $68,000 and represented 611 times the average monthly salary.

When Pepsi refused to pay, riots broke out and a teacher and a 5-year-old child died when a grenade thrown at a Pepsi truck exploded on a crowded street. Several courts subsequently sided with Pepsi, which ultimately did not have to pay any of the billions the Filipinos sought to claim.

Instead of the two expected winners, thousands of Filipinos came to claim the prize.

So people took to the streets to celebrate – thinking that they had all become millionaires overnight and that they were all in for a skyrocketing salary.

Some confusion – and even concern – prevailed, however, as the number of self-proclaimed winners was far higher than imagined.

But most didn’t care: In their eyes, they had won fair and square, and the multibillion-dollar soda conglomerate had to foot every payment.

Ultimately, Pepsi had made a mistake.

A computer glitch had printed the winning number 349 on far more bottle caps than expected – out of a staggering 800,000.

That meant Pepsi would have to pay some $32 billion to keep its promise – and hundreds of people rushed to the country’s main bottling plant to collect their winning capsules.

It quickly had to be closed and guarded by the police, when it became clear that payments would not be easy.

Throughout the contest, Pepsi had complete control over the number of winners, relying on a computer program to generate the winning caps.

Two winning selections meant there could only be two winners – and Pepsi would stay within its budget while still benefiting from the promotion, or so the executives thought.

A computer glitch had printed the winning number 349 on far more bottle caps than expected – out of a staggering 800,000.

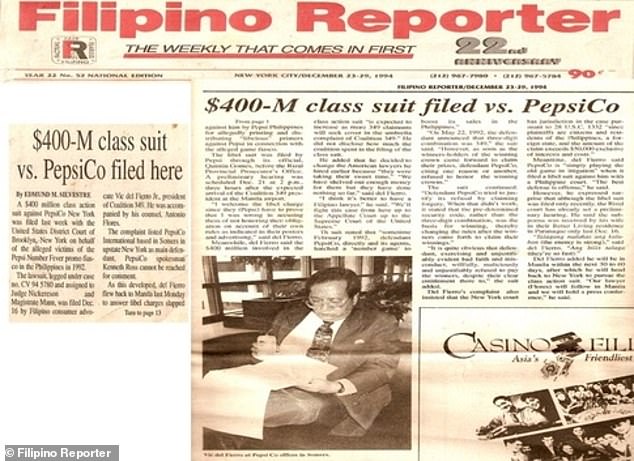

The violence would continue for most of the year, although the 349ers eventually took a more Ogranized approach. they elected a local preacher, Vid del Fierro (seen here) as leader. He amassed over 800,349 winners in an attempt to sue Pepsi for over $400 million.

Pepsi, currently valued at $226 billion, did not budge, leading to violent protests and riots that ultimately left five people dead.

As for 349, it was one of several numbers designated as non-winning – and as such, bottling plants were free to print it as much as they wanted.

349 was so common that many people had more than one, and the streets of several cities that night were filled with celebrations.

Pepsi executives quickly realized they had made a big mistake and called an emergency meeting later that night to find a solution.

Since it would have cost them tens of billions of dollars to honor each winning cap, they decided to blame the computer program and offered 500 pesos for each winning cap.

This sum was an insult to many, because it only cost about five US dollars.

Some accepted Pepsi, but most refused and became even more furious.

Uninfluenced by an invisible computer error, they ruled that the multi-billion dollar company should honor the full amount of the prize.

But Pepsi, currently valued at $226 billion, didn’t budge, leading to violent protests and riots that ultimately left five people dead.

Dozens more were injured when 349 Winners stormed Pepsi factories while throwing Molotov cocktails, often into the windows of moving Pepsi trucks that passed by.

Several courts later sided with Pepsi, which ultimately did not have to pay any of the billions that frustrated Filipinos had sought to demand.