Astronomers are revising their understanding of how stars and planets form after the James Webb Space Telescope detected six new “rogue” worlds.

These strange planets are free-floating objects that are not tied to any host star. In most cases, they have been violently ejected from their celestial vicinity by the gravitational force of a nearby object.

But these newly discovered rogue worlds 1,000 light-years from Earth are unusual in that they appear to have never belonged to a solar system: They formed independently of any host star.

Observing them with James Webb has already caused researchers to rethink everything we know about how stars and planets are born.

“We’re probing the limits of the star formation process,” said study lead author Adam Langeveld, an astrophysicist at Johns Hopkins University.

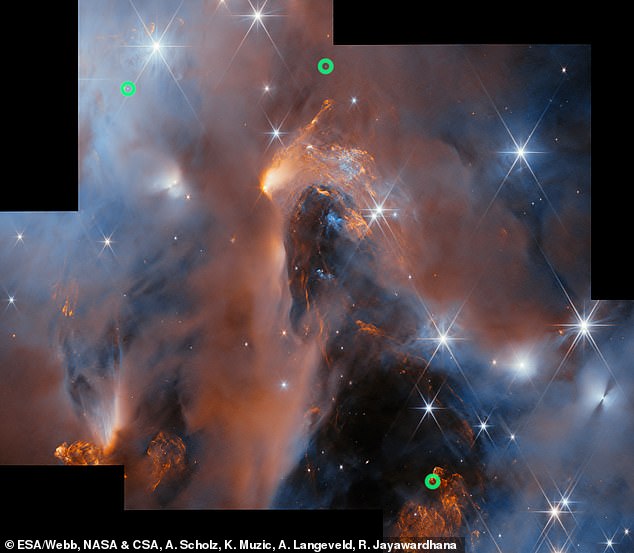

A new image from JWST shows the nebula NGC1333, which contains six “rogue” worlds that could change our understanding of how stars and planets form.

Their study found evidence of a new process of world formation.

Instead of growing into planets and then being ejected from their host star, these rogue worlds began forming into stars but failed to ignite.

Langeveld and his colleagues published their findings today in The Astronomical Journal.

Using James Webb’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS), an instrument consisting of two main components: cameras and spectrographs.

Cameras capture images of space, and spectrographs spread light into a spectrum so researchers can measure each wavelength.

NIRISS enabled the research team to conduct the most in-depth study to date of the young nebula NGC1333, a star-forming cloud located in the constellation Perseus.

Webb peered through the gas and dust to produce a surprisingly detailed image of the inner nebula, glowing with young stars.

Researchers measured the infrared light spectrum of every object Webb observed inside NGC1333 and discovered several rogue worlds hiding within.

Webb’s observations indicated that these six rogue worlds are gas giants roughly five to ten times more massive than Jupiter.

But Webb’s observations suggest they didn’t start out as planets.

They actually arose from a process that typically produces stars and brown dwarfs, objects that sit on the boundary between stars and planets but never become luminous.

This led the research team to ask an important question: Could an object that looks like a young Jupiter have become a star under the right conditions?

The green circles in this image highlight three of the rogue worlds that JWST discovered hiding within NGC1333.

JWST observations have complicated the classification of stars and planets, because the rogue worlds resemble gas giants and brown dwarfs but do not fit into either category.

“This is an important context for understanding star and planet formation,” Langeveld said.

The most puzzling of these six rogue worlds is the lightest object with a “dusty disk” found to date.

A dusty disk, also known as a circumstellar disk, is a circular cloud of gas and dust orbiting a newly formed star.

This object has a mass Roughly equivalent to five Jupiters (or 1,600 Earths), the presence of the disk suggests that the object formed as a star.

“This raises a question that challenges star formation theories: how could an object with a mass just a few times that of Jupiter form directly from a contracting cloud of gas and dust?” Langeveld told DailyMail.com in an email.

What’s more, these findings suggest that “mini” planets and planetary systems could form in the disk of this rogue world, as planets are known to take shape within circumstellar disks.

“If so, it would likely resemble Jupiter or Saturn (due to the object’s mass), for example, with moons and/or rings, rather than a system analogous to our solar system with larger planets,” Langeveld said.

“This whole area is uncharted territory,” he added.

‘We have not found ‘moons’ or companions around such light objects outside our solar system before, so it is important to continue investigating them in the future.’

These new findings complicate the classification of stars and planets because the masses of rogue worlds overlap with those of gas giants and brown dwarfs, but the process of their formation sets them apart.

“Our observations confirm that nature produces planetary-mass objects in at least two different ways,” lead author Ray Jayawardhana, an astrophysicist and provost at Johns Hopkins University, said in the news release.

The first is “the contraction of a cloud of gas and dust, as stars form,” and the second is “in disks of gas and dust around young stars, as Jupiter did in our own solar system.”

The research team plans to continue studying these unusual objects and compare them to heavier brown dwarfs and gas giant planets.

“A more complete picture of the birth of stars and planets would help us understand how our own solar system came into being and how our planetary system fits into the larger cosmic context,” Jayawardhana told DailyMail.com in an email.