It was two in the morning when there was a knock on the door. I was 32 years old and a postgraduate student in anthropology at the University of Roehampton. I was living alone in a rented flat and still working on my thesis. Normally I wouldn’t answer the door this late, but something told me it was important. As soon as I saw it was the police, I knew someone had died.

I was told that my father’s body had been discovered by his maid at his home in Bedfordshire. My friendly pet, Mr Cuddles, heard the voices and came out to greet me as I stammered that I wasn’t supposed to have pets. The officer assured me that it wasn’t his job to police whether people were complying with the terms of their tenancy agreements.

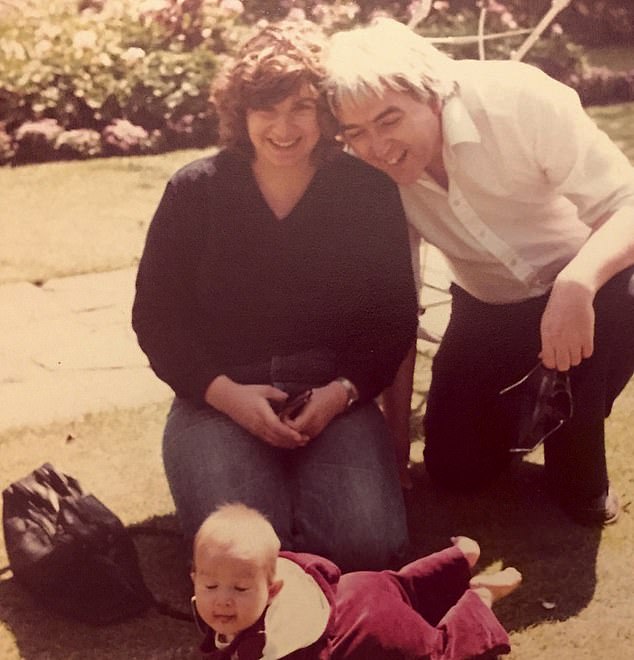

The three, London 1981

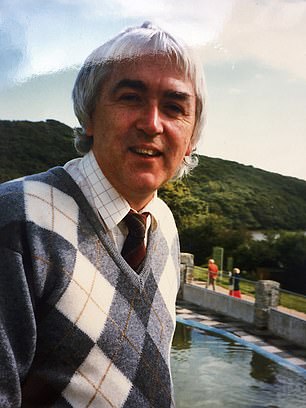

A few days later, the coroner phoned me with the autopsy results: my 69-year-old father had died of a massive aneurysm. He had been having some problems for a while (he was diabetic and had undergone a heart bypass a few years earlier), but was otherwise healthy and working full-time as an IT consultant. His death was a huge, unexpected blow.

My father was an award-winning amateur musician, a former Cambridge mathematics student and a successful businessman. He even worked as a church organist. He had a good life and a good death: painless and without any long-term illness or suffering. He finished work, sat down in his chair and simply collapsed. I think he died satisfied that he had achieved everything he had set out to do in life. His death was sad, but it was an orderly death.

Dad in the mid-90s; mum at home in North London, 1981

Her house was spotless. Everything I needed was in a folder marked “death” on a shelf. She had included a copy of her will, her birth certificate, and even all of her insurance policies. I didn’t have to do anything but grieve her loss.

It was not the first time I had lost a loved one. My grandparents died when I was young, my paternal grandmother before I was born. I grew up as an only child, with my parents Roy and Lyn, my maternal grandmother Edie and my beloved Aunt Jean, who died in her 60s after routine surgery. I was in my early 20s and it was my first major bereavement. My grandmother passed away a few years later, at nearly 90.

But when my father died in 2013, I was the first of all my friends to lose a parent. I became aware of the relationships they had with their own parents. As the years passed, my friends began to deal with the issues of aging mothers and fathers: dementia, physical disabilities. I missed my father, but I was grateful to have been spared that torment.

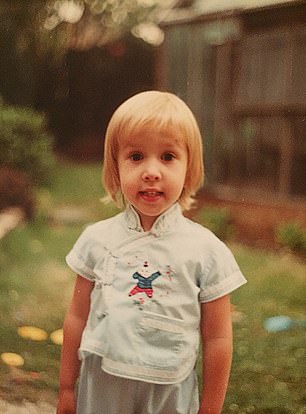

Me at three years old; Mom, Cambridge, 1975

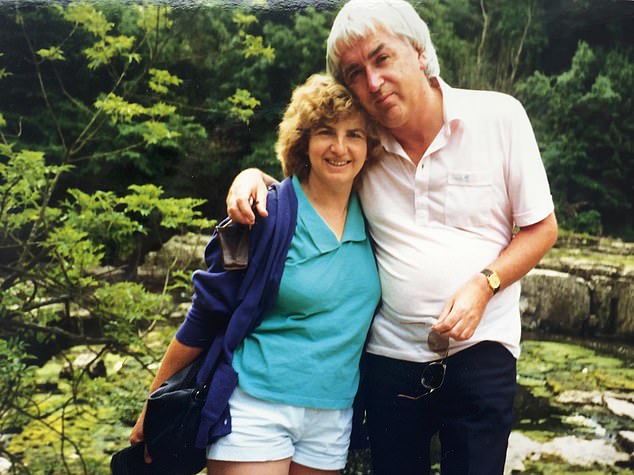

Meanwhile, my relationship with my mother was troubled and tumultuous: we had been estranged for years after she became romantically involved with a man who treated me poorly. But after my father died, I felt pressure to rebuild the mother-daughter relationship. I was acutely aware that she was the only family I had left.

By this time, I had already given up anthropology and was writing plays full-time. My mother was very proud of me. The first time a play was staged in the West End, in 2017, she dressed up, invited me to afternoon tea before the performance, and then put her hand up during the post-performance Q&A to ask the director, “Why aren’t you programming more plays by this incredibly talented young writer?” I was mortified, but also secretly pleased. I was happy to have made her proud of me. What I didn’t know was that, within a couple of years, she too would be dead at 68, and I would be alone in the world at the age of 37.

Mum and Dad in North Yorkshire, 1989

In May 2018, I was in Bristol attending a theatre conference. When the event was over, I had a panic attack for no apparent reason and returned to London early. I wasn’t consciously thinking about my mother, but worries about her and her romantic relationship were always in the background.

A few months earlier she had told me that she had called a domestic violence charity. They had put her in touch with a solicitor who specialises in domestic violence cases and who was helping her evict her boyfriend.

She told me that they had basically broken up, they slept in separate rooms and no longer had a real relationship; he was controlling and she was scared of him and what he might do if she told him to leave.

When I was a little boy, 1982

The morning after I returned from Bristol, I woke up to a voicemail from his number, but it was his voice on the recording telling me he had died. I got on a train to the hospital, where I saw his body in the morgue, with an incongruous apricot-coloured frilly duvet cover concealing the black body bag underneath.

The coroner said the autopsy showed she had died of a stroke, but when I spoke to her boyfriend the next day, he told me that the doctors had told him she would be disabled if she lived, so they had asked him to make a decision about whether to resuscitate her or not. He had told them to “pull the plug.” Years later, one of the doctors who had treated her told me that was a lie.

At four years old, chasing ducks with mom

To this day I don’t know what happened, only that my mother’s boyfriend returned home before his body had cooled down and ransacked the place looking for her will. When he discovered she had left me everything, he squatted there for six months, padlocking the door as a final act of cruelty when he fled at midnight to avoid being forcibly evicted.

If my father’s death had been orderly, my mother’s was as messy as her life. My beautiful, absent-minded, spiritual mother, who loved to sing as loud as possible and believed in feng shui and crystal healing, brought chaos with her as she lurched from one drama to the next. And she left chaos behind – not just her duplex in Harrow, which was in a state of “semi-hoarding”, but legal and personal chaos too.

At age 11, with my pet ‘Acorn Corny Rabbit’; a holiday in the late 80s in Israel

There was no room for feelings. I shut out my pain, but I would wake up crying. I would get very angry when my friends would complain about their parents’ little flaws: at least you have parents, I guess. Be grateful and spend this precious time with them.

I felt guilty for not doing more to rescue my mother. After she died, I found emails she had sent to a friend, expressing her hope that I would show up and take her to a hotel. But I was also angry at her for not putting my needs first, for raising me as a paternalized child, forced into the role of a caring adult. I needed to get over that anger before I could grieve.

With mom in London, 1984

I was so traumatised and, perhaps overwhelmed by the enormity of my losses, afraid that my grief and bad luck would be contagious, that I withdrew from old friends and other people. The only thing that saved me was writing. In 2019, the Bush Theatre in London commissioned my play Unicorn, which explores my mother’s early life; I later wrote the award-winning interactive play Batman, which invited the audience to take part in a wake on stage. Talking about grief and writing about my mother finally helped me process all the emotions and feelings I had been repressing.

My theatre career has taken me all over the world and I have used this opportunity to fulfil my mother’s unfulfilled wish to travel by scattering her ashes in nearly a dozen countries so far, including the Galapagos Islands in Ecuador, the Caribbean Sea off Mexico, the Seine in Paris and of course the Thames in London.

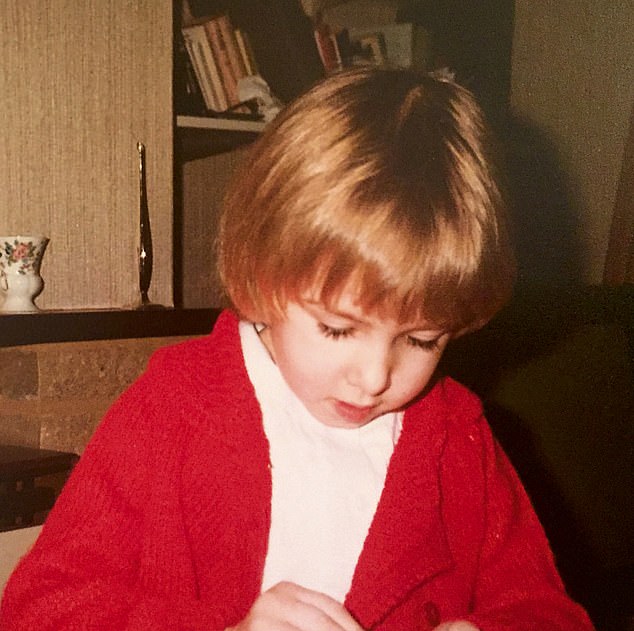

In my favorite cardigan, 1987

She wasn’t the perfect mother, but she had wonderful qualities. She never judged anyone and had a deep love of animals, which I share (I made a donation to Dogs Trust in her name). I’ve always been very independent and live alone, but loss made me realise how much I need people; that it’s okay to open up, to accept love and affection and to ask for support. I’ve learnt to use my writing to connect with others, to encourage collective grief, and that brings me great joy.

My parents’ absence will always be a void in my life, but their deaths have taught me that I am not alone.

With Dad in Eastbourne, mid 80s

Happy Death Club by Naomi Westerman is published by 404 Ink, £7.50. To order a copy for £6.75 until 18 August, visit mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937. Free UK delivery on orders over £25.