Animal behavior researchers have released an incredible video of pint-sized capuchin monkeys using stone tools to forage for food in Brazil’s Ubajara National Park.

The team recorded 214 cases in total, capturing the creatures’ attempts to extract food, such as “trapdoor” spiders, from the arachnids’ underground nests.

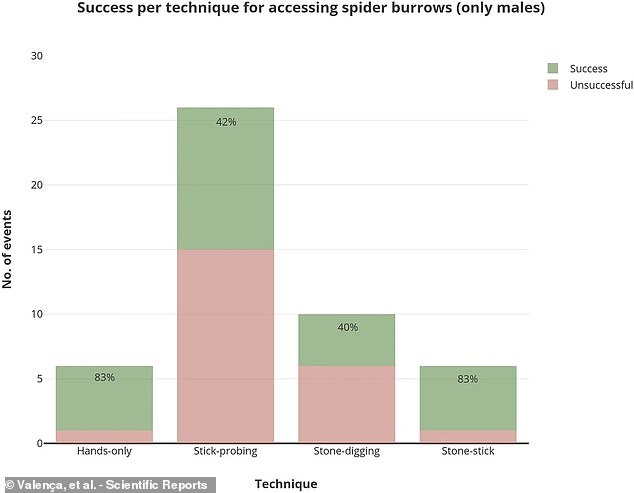

The researchers then divided these cases into four methods: “hands-only” digging, “stone digging”, “stick probing”, and “stick and stone” hybrid use, and found that the monkeys changed their habits depending on the seasonal weather and the right tools for the job.

The footage joins a growing number of studies looking at the small South American primate’s use of stone tools and sticks, an emerging field that some research universities now describe as “documenting the Stone Age of the Monkey in real time.” .

The new findings come on the heels of other recent discoveries that further reveal the intelligence of humanity’s primate cousins, including an orangutan’s impressive practice of healing his own wounds with a medicinal herb he prepared himself.

Animal behavior researchers have released an incredible video of pint-sized capuchin monkeys using stone tools to forage for food in Brazil’s Ubajara National Park (video still above)

The team recorded 214 cases in total, in which the creatures attempted to extract food, such as “trapdoor” spiders, from buried underground nests (video still above). They studied the monkeys’ digging techniques and their strategic adaptations to local ecological conditions.

This understanding that South American capuchins (which typically don’t measure much more than 22 inches, apart from their 17-inch-long tails) use tools like their larger primate relatives has emerged only gradually since the mid-1990s. of 2000.

In 2004, botanist Alicia Ibáñez noted in passing in her book on plant life that white-faced capuchin monkeys used rocks to crack almonds and shellfish in the open sea.

Their discovery on the islands of Panama’s Coiba National Park soon inspired scientists at the University of California, Davis to study these capuchins.

“Those islands are the only place in the world where this particular species of monkey is known to use stone tools,” according to the primate researcher at the University of California, Davis. Meredith Carlson. “It’s really concentrated in two small towns.”

But within a few years, animal psychologists at the University of São Paulo in Brazil would make a similar discovery in the dry savanna of their country’s Serra da Capivara National Park.

The Beard Capuchin species there, reported in his 2009 article“It would routinely modify and use sticks as probes to dip for honey and flush prey (such as lizards, bees, and scorpions) from crevices in rocks and logs.”

And now the latest study, published in Scientific Reports This May, it expands the terrain these capuchin monkeys dig for food to the wetter savannah regions of another Brazilian national reserve: Ubajara National Park, near the Atlantic coast.

Researchers from the University of São Paulo from the Capuchin Culture Project spent 21 months observing and recording capuchins hard at work digging for food.

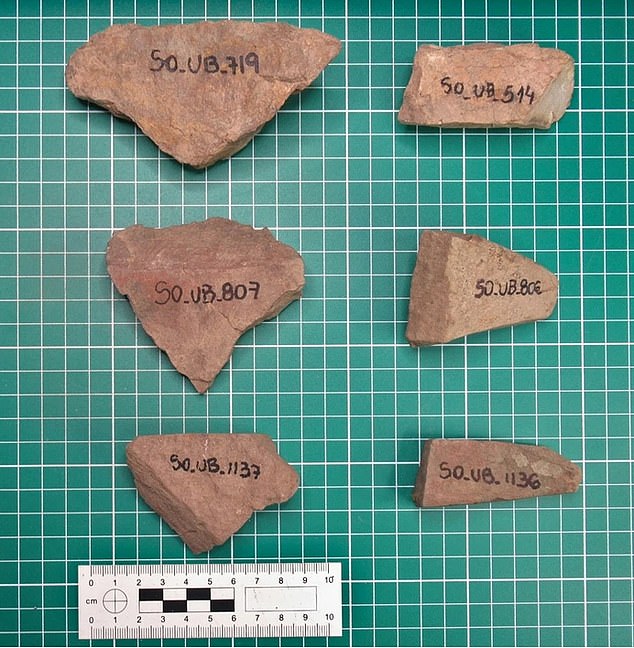

When it came to digging stones, the researchers noted that bearded capuchins used “smaller, lighter” rocks “made of sandstone materials” (samples pictured above) compared to “tools used to crack palm nuts.” , which were heavier rocks.

They also observed that the monkeys used sandstone tools during 59 percent of digging attempts on hills (as seen above), but only in 24 percent of digging attempts along river banks, suggesting that they were aware that soft, moist soil was gentler on their tiny monkey paws.

When it came to digging stones, the researchers observed that these bearded capuchins used “smaller, lighter” rocks “made of sandstone materials” compared to “hammer tools used to crack palm nuts.”

The average weight of their sandstone digging tools came to about 4.5 ounces, compared to about 2.5 pounds for their palm nut cracking rocks, suggesting a concerted strategy about which “tool” might work best. in each case.

The team also observed that the monkeys used sandstone tools during 59 percent of digging attempts on hills, but only in 24 percent of digging attempts along river banks, suggesting that They were aware that the soft, moist earth was softer for their monkey paws.

“We predict that capuchin monkeys use only their hands in looser soils,” the researchers wrote, “and dig stones in harder, compacted soils.”

“In addition, we also hypothesize that capuchin monkeys actively choose the position of stone tools,” they added, “and that this increases efficiency when digging in difficult soils.”

When it came to the monkeys’ use of the stick, which the researchers observed on 40 documented occasions, 32 cases were specifically for raiding spider burrows. Above, two sticks used by capuchin monkeys, measured by scientists.

While the monkeys were successful on only 42.5 percent of their stick-poking attempts, the researchers noted that the stick test seemed to involve complex reasoning and skill. Above, a monkey pushes with a leaf-covered stick in an effort to obtain and eat a spider.

When it came to the monkeys’ use of the stick, which the researchers observed on 40 documented occasions, 32 cases were specifically for raiding spider burrows.

While the monkeys were successful on only 42.5 percent of their stick-poking attempts, the researchers noted that the stick test seemed to involve complex reasoning and skill.

“Adult males sometimes hold the probe in one hand and place the other on the side of the burrow,” the researchers wrote, “apparently to prevent the spider from falling and escaping.”

The scientists, whose work for the University of São Paulo was carried out in collaboration with Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Animal Behavior and its Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology, noted a similar complexity in the “stone stick” tactic.

Capuchins first used stone to scrape surface dirt, reducing the depth of spider burrows to make their probing work with sticks easier and more effective.

The monkeys then used the sticks to extract spiders and their protein-rich egg sacs.

While the monkeys were successful on only 42.5 percent of their stick-poking attempts (second from the left above), the team noted that the stick test seemed to involve complex reasoning and skill. Interestingly, the use of tools did not seem to improve their ability to obtain food.

cApuchin monkeys are an omnivorous species, meaning their diet varies in the wild.

Everything from flowers, buds and leaves to birds, eggs, small mammals, mollusks and insects are all on the menu for this little primate.

Interestingly, the researchers noted that the monkeys’ use of tools didn’t actually seem to improve their ability to reach the food: The monkeys’ success rate was around 83 percent in both the “hands only” and in the “stone stick”. For example.

And the efforts of the monkeys with stones and sticks separately were just under half.

“It is intriguing that tool use did not increase overall success in obtaining underground food resources,” the researchers said.

But they noted that this could only have seemed that way, because their study could not determine whether the monkeys were specifically turning to tools for other reasons, “to obtain greater resources” or “to reduce the duration of digging.”