A “mass casualty” event has been declared in Baltimore after the Francis Scott Key Bridge was struck by a container ship and collapsed into the Patapsco River.

As rescuers continue to search for survivors, many wonder how the bridge could have collapsed so quickly, having been standing since 1977.

Speaking to MailOnline, engineers explained that while the bridge was not inherently unsafe, its “flimsy” structure meant it was prone to collapse if the supports were damaged.

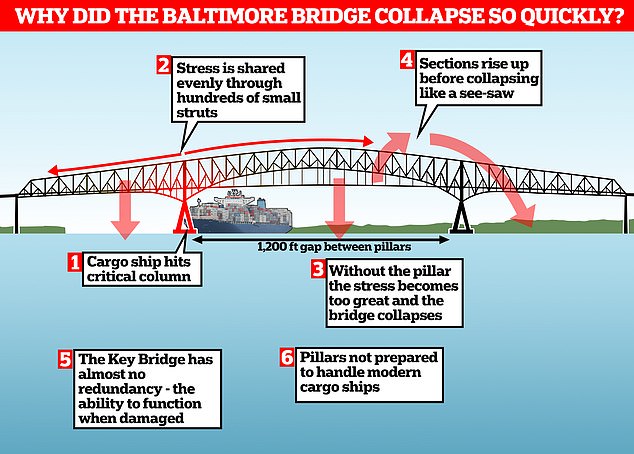

Julian Carter, a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers, told MailOnline that knocking down the support pillar had the same effect as collapsing a house of cards.

“When you remove one of the supports, a catastrophic failure occurs because all those parts that are interconnected suddenly become overloaded,” he said.

Speaking to MailOnline, engineers explained that while the bridge was not inherently unsafe, its “flimsy” structure meant it was prone to collapsing if the supports were damaged.

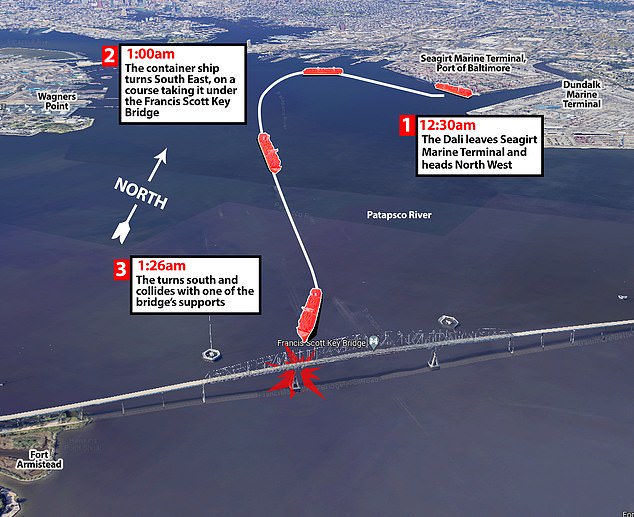

The Baltimore Bridge collapsed at 1:30 a.m. local time after a freighter traveling from a nearby port struck a support column.

The Francis Scott Key Bridge, or Key Bridge as it is commonly known, is a critical transportation link and is one of only three ways to cross the Baltimore Harbor.

Opened in 1997 to carry Route 65, the Key Bridge spanned 1.6 miles (2.6 kilometers) of the Patapsco River.

What made the bridge so unique were the long lengths between the supporting pillars.

With its longest span between supports, or span, spanning 1,200 feet (366 m), this made it the third-longest span of unsupported road in the world.

Unfortunately, this same unique feature may have contributed to the speed of its collapse.

As Mr. Carter explains, the Key Bridge is a continuous truss bridge, meaning it is supported by beams arranged in triangular shapes called “struts.”

When the weight of the vehicles is applied to the bridge, that force is distributed throughout the structure and each strut participates in the load.

The bridge collapsed seconds after impact, throwing large chunks of steel and conductors into the water.

Experts say truss bridges like the Key Bridge cannot survive impacts to their supporting piers.

Because the spaces between the pillars are so large, these supports must be as light as possible so that the bridge does not collapse under its own weight.

“They have very little redundancy and that means each party is working very hard,” Mr Carter said.

“This particular one has long spans that are continuous and that means that from one side of a stand to the other, all the parts are connected.”

In combination, these two characteristics (interconnected parts and low redundancy) mean that if something goes wrong, the results quickly become disastrous.

Carter told MailOnline that knocking down the support pillar had the same effect as collapsing a house of cards.

He explained: “This structure really relied on force from one side to the other and once that was taken away, it collapsed.”

Once the pillar was struck, the weight of the bridge suddenly redistributed and overloaded the structure. This led to a rapid collapse.

Dr Andrew Barr, a civil and structural engineer at the University of Sheffield, describes this as an example of “progressive collapse” where the failure of one part leads to others also failing.

Dr Barr said: “In this case, the collapse of the pier caused the truss that was now unsupported on it to bend and fall.”

This also explains why images of the collapse show the northern span of the bridge rising into the air before collapsing.

Since everything is held together in a single structure, the truss rotated on the remaining support pillar like a see-saw before the forces became too great and the span collapsed.

Experts say modern cargo ships like the Dali (pictured) are much larger than the Key Bridge would have been able to support.

Experts say it was almost inevitable that the bridge would collapse after being hit in this way since the piers are never designed to withstand the full force of a ship.

An impact like this was almost certain to lead the Key Bridge to a catastrophic collapse, experts said.

Bridge builder and civil engineer Ian Firth said: “The support is a very, relatively, flimsy structure when you look at it, it’s a sort of trestle structure with individual legs.”

“So the bridge has collapsed simply as a result of this enormous impact force,” Firth said. he told the BBC.

Likewise, Dr Masoud Hayatdavoodi, a civil engineer and naval architect at the University of Dundee, says: “There is no doubt that the bridge would collapse due to the impact on the columns.”

Dr Hayatdavoodi added: “Bridges are not designed to support lateral loads from ships on their columns. While they can withstand lateral loads comparable to the water currents and wind loads of a small ship, the force exerted by the impact of a container ship is significantly greater.’

However, it is not necessarily true that the Key Bridge and other similar truss bridges are inherently dangerous or poorly designed.

Rather, the Key Bridge was simply never designed to withstand a direct collision from a modern container ship.

Police and rescue teams are still searching the water for survivors, but police say at least seven are believed to have fallen into the river.

The ship that hit the Key Bridge was the Dali, a Singapore-flagged container ship that had departed from the Seagirt Marine terminal at 12:30 that night.

At almost 300 m (1,000 ft) long and 48.2 m (158 ft) wide, this ship could easily be twice the size of those from 50 years ago.

Toby Mottram, emeritus professor and structural engineer at the University of Warwick, said: “Despite meeting regulatory design and safety standards from the 1970s, the Baltimore Key Bridge may not have been equipped to handle the scale of ship movements observed today”.

For most people who use truss bridges, there is no reason to fear that their bridge could collapse unless it is also hit by a container ship.

While it may seem far-fetched, Carter told MailOnline the risk can be compared to the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

He added: “This is one of those events that happen occasionally, like Fukushima, where people in the industry have ruled out a particular risk for whatever reason.”

“Now, all of a sudden, it’s happened that people have to recalibrate the management of waterways and traffic.”