It’s been nearly four decades since scientists discovered the growing hole in Earth’s ozone layer.

But climate researchers now say the protective shield, about 20 miles above our planet’s surface, could be on its way to recovery.

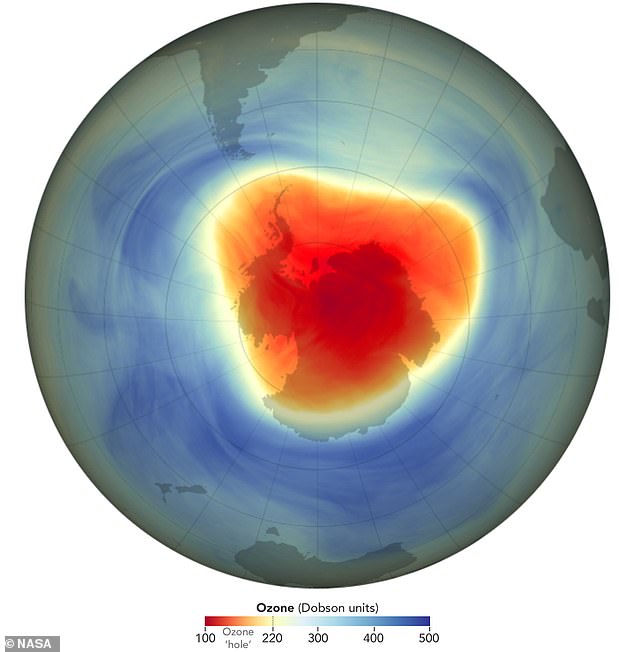

New data collected by NASA shows that the ozone hole over Antarctica this year was the seventh smallest since 1992.

NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predict that the layer could fully recover by 2066.

Dr Paul Newman, leader of NASA’s ozone research team, says: “The Antarctic hole of 2024 is smaller than ozone holes observed in the early 2000s.

“The gradual improvement we have seen over the past two decades shows that international efforts that curbed ozone-depleting chemicals are working.”

However, the ozone hole still covered an average of nearly 20 million square kilometers (8 million square miles), three times the size of the contiguous United States.

Scientists warn that there is still a long way to go before the ozone layer returns to its natural thickness.

NASA has revealed that the hole in the ozone layer (pictured) this year reached its seventh smallest size since 1992.

As the ozone hole opens, higher levels of harmful UVB radiation are allowed to reach Earth, increasing the risks of cancer and cataracts.

Each year, a combination of ozone-depleting chemicals and cold temperatures combine to open the annual ozone hole over Antarctica.

While this hole still allows harmful ultraviolet radiation to rain down on Antarctica each year, it has recently begun to show promising signs of recovery.

Using a combination of satellite observations and ground-launched weather balloons, NASA and NOAA have measured the concentration of ozone gas in the atmosphere.

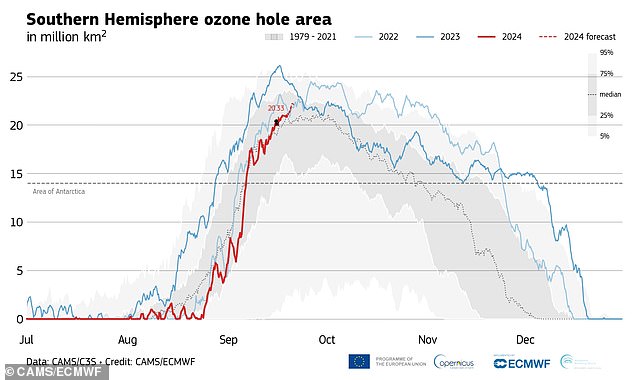

Their observations revealed that the annual ozone layer over the South Pole was relatively small compared to other years during its peak depletion between September 7 and October 13.

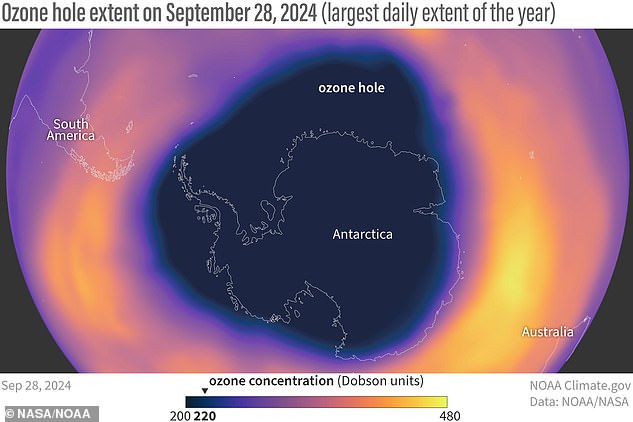

At its greatest extent, on September 28 of this year, the ozone hole covered an area of 8.5 million square miles (22.4 million square kilometers).

This is in stark contrast to 2023, during which the ozone hole peaked at 10 million square miles (26 million square kilometers) on September 10.

While still significant, it is the 20th smallest hole since records began in 1979 and the seventh smallest since ozone-depleting CFCs were banned under the Montreal agreement.

At its largest this year, the ozone hole was 8.5 million square miles (22.4 million square kilometers) on September 28. This is 1.5 million square miles smaller than the maximum size in 2023.

Scientists from NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) measured the ozone layer over Antarctica using satellites and weather balloons (pictured). They now predict that the ozone layer could fully recover by 2066

CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons) are a type of human-derived chemical that was widely used in aerosols and refrigeration.

Since they were banned in 1992, the concentration of CFCs in the atmosphere has gradually decreased, allowing the ozone layer to begin to recover.

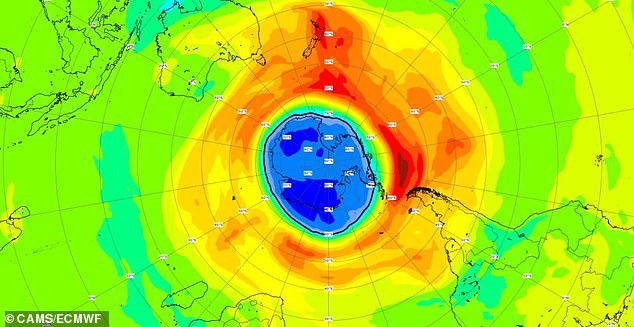

A recent study by the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS) found that the ozone hole had taken longer to form and was smaller than expected.

On September 13, the ozone hole was 18.48 million square kilometers (7.13 million square miles), smaller than at the same time in recent years.

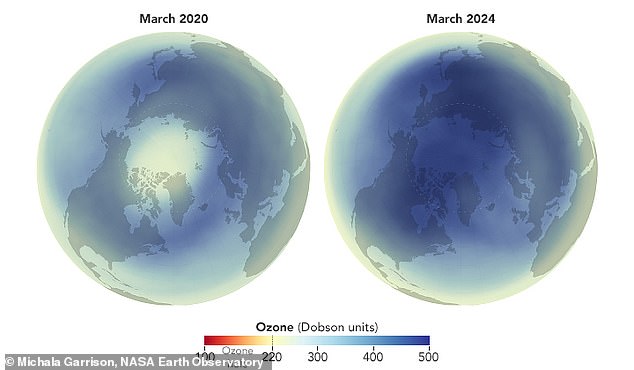

Meanwhile, the ozone layer over the North Pole has also shown signs of possible recovery.

This year, particularly favorable weather allowed the Arctic ozone layer to become 14.5 percent thicker than the post-1980 average.

According to NASA and NOAA predictions, this means that the ozone layer could regain its pre-hole thickness in just over 40 years.

Scientists believe the recent recovery is due to a combination of the natural decline of CFCs and the influx of ozone from areas north of the pole.

In September of this year, the ozone hole (pictured in blue) was 7.13 million square miles, smaller than the same period in recent years. Researchers suggest this is a sign that the CFC ban is allowing the ozone layer to recover naturally.

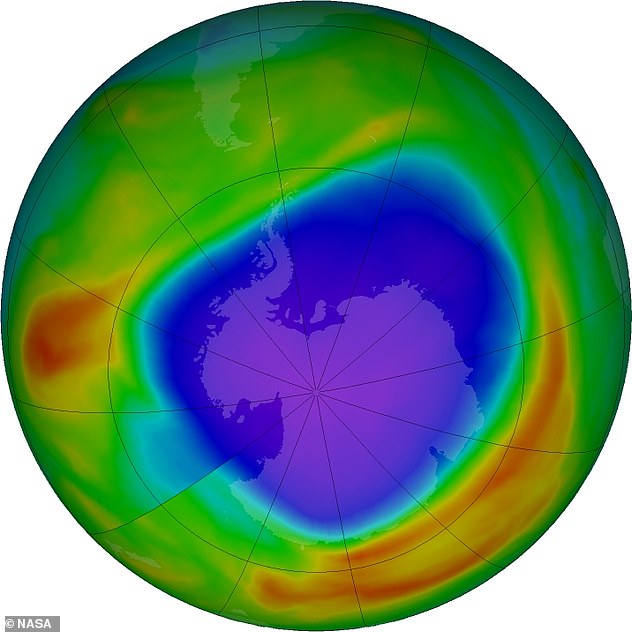

The ozone layer still has a long way to go to recover. On October 5 of this year (pictured), the layer reached a thickness of just 109 Dobson units, less than half the pre-1979 average.

Ozone that has built up in the stratosphere normally absorbs almost all of the radiation coming from the sun, protecting life on Earth from harmful radiation.

During the winter months, circular winds called the Polar Vortex often concentrate ozone-depleting chemicals in a small area above the South Pole.

Then, when the sun’s energy begins to reach the atmosphere in spring, the combination of cold temperatures and solar radiation begins to erode the ozone layer.

However, in June Antarctica experienced two rare “sudden stratospheric warming events” that caused temperatures in the upper atmosphere to rise by 15ºC (27ºF) and 17ºC (30.6ºF), respectively.

These spikes significantly weakened the polar vortex, reducing the depletion rate and allowing more ozone to reach the area over the pole.

However, NASA also warns that the ozone layer still has a long road to recovery.

Stephen Montzka, senior scientist at NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory, says: “By 2024, we can see that the severity of the ozone hole is below average compared to other years in the last three decades, but the ozone layer “She is still far from being completely cured.” .’

Scientists measure the thickness of the ozone layer using a measurement called Dobson units, where anything less than 220 Dobson units (DU) is considered an ozone hole.

At its thinnest point this year, on October 5, the atmosphere over Antarctica measured just 109 DU.

Recent studies have shown that the ozone layer is making promising strides toward recovery. This graph shows that the ozone hole in Antarctica formed later and was smaller than expected this year

Researchers have found that the ozone layer over the Arctic reached a record thickness in March 2024 (right). This is in stark contrast to March 2020 (left), when an unprecedented ozone hole opened over the pole.

This is somewhat thicker than the lowest level ever recorded when the ozone layer reached 92 DU in 2006, but still thin enough to create serious health risks.

A recent study even found that Antarctic wildlife, such as seals and penguins, are at increased risk of sunburn due to ozone depletion.

According to NOAA research chemist Bryan Johnson, 225 Dobson units was typical for the ozone layer over Antarctica in 1979.

“Therefore, there is still a long way to go before atmospheric ozone returns to levels before the emergence of widespread CFC pollution,” he said.