For the first time, ‘mini-organs’ have been grown from human stem cells extracted during the late stages of pregnancy, marking a ‘major step forward’ for prenatal medicine.

New research shows that complex cell models, called organoids, can be grown and that these “mini-organs” retain the baby’s biological information.

The breakthrough means that for the first time human development can be observed in late pregnancy, increasing the possibility of monitoring and treating congenital conditions before birth.

Organoids (miniaturized, simplified versions of organs) allow researchers to study how organs function both when healthy and when affected by disease.

Until now, organoids have been derived from adult stem cells or fetal tissue from terminated pregnancies, and regulations restrict when fetal samples can be obtained.

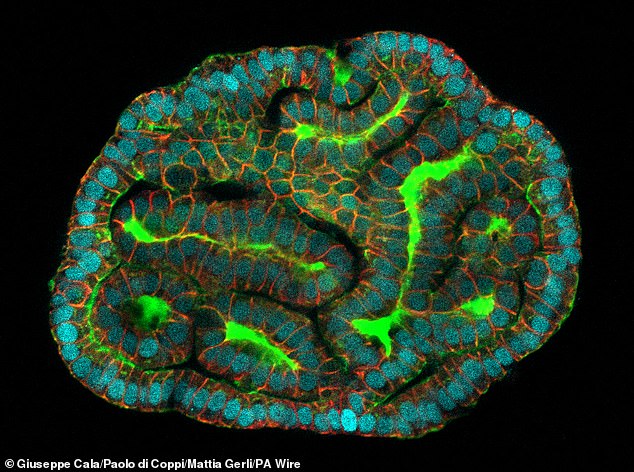

For the first time, ‘mini-organs’ have been grown from human stem cells extracted during the late stages of pregnancy, marking a ‘big step forward’ for prenatal medicine. In the photo: a mini kidney

In the UK this can be done up to 22 weeks after conception, the legal limit for terminating a pregnancy, but in countries such as the United States fetal sampling is illegal.

The regulations mean that the study of normal human development after 22 weeks has been limited, as well as congenital diseases at a time when there may still be an opportunity to treat them.

To overcome these problems, researchers from University College London (UCL) and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) extracted stem cells that had passed into the amniotic fluid, which surrounds the child in the womb and protects it during pregnancy.

Because the child is not touched during the collection process, sampling restrictions can be overcome and the cells contain the same biological information as the child.

The researchers took live cells from 12 pregnancies (between week 16 and week 34) as part of routine diagnostic tests.

They then identified which tissues the stem cells came from.

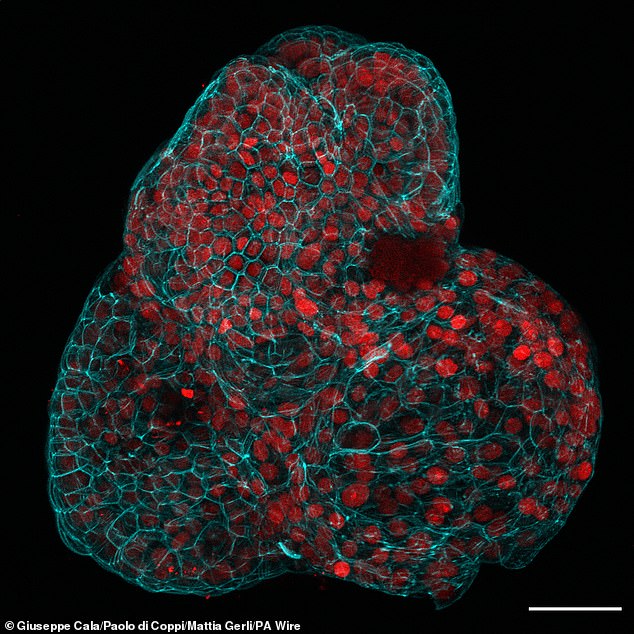

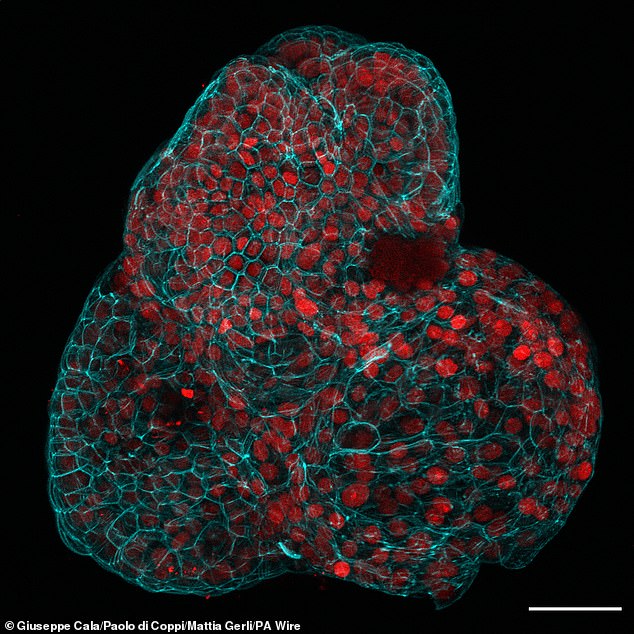

Stem cells were successfully extracted from the lungs, kidneys and intestine and used to grow organoids that had functional characteristics of these tissue types.

Dr Mattia Gerli, first author of the study, said: “The organoids we created from amniotic fluid cells exhibit many of the functions of the tissues they represent, including gene and protein expression.”

Stem cells were successfully extracted from the lungs, kidneys and intestine and used to grow organoids that had functional characteristics of these tissue types. In the photo: the mini lung

«They will allow us to study what happens during development, both in health and disease, something that had not been possible before.

“We know very little about late-stage human pregnancy, so it is incredibly exciting to open up new areas of prenatal medicine.”

The team worked with researchers at KU Leuven in Belgium to study the development of babies with CDH, a condition in which a hole in the diaphragm means organs such as the intestine and liver move towards the chest, putting pressure on the lungs and hindering healthy growth.

Miniorgans from babies with CDH before and after treatment were compared with organoids from healthy babies to study the biological characteristics of each group.

The study found significant differences in development between healthy and pre-treatment CDH organoids.

However, the organoids in the post-treatment group were much closer to healthy ones, providing an estimate of the treatment’s effectiveness at the cellular level.

NIHR Professor Paolo de Coppi, lead author of the study from UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health and Great Ormond Street Hospital, said: “This is the first time we have been able to carry out a functional assessment of the congenital condition of child”. before birth, which represents a great step forward for prenatal medicine.

‘Diagnosis is usually based on imaging such as ultrasound or MRI and genetic analysis.

‘When we meet families with a prenatal diagnosis, we often can’t tell them much about the outcome because each case is different.

“We’re not claiming we can do it yet, but the ability to study functional prenatal organoids is the first step toward being able to provide a more detailed prognosis and hopefully provide more effective treatments in the future.”

The researchers say that while they have not yet studied the method in relation to other conditions, they may be able to look at other conditions that affect the lungs, such as cystic fibrosis, kidneys and the intestine.

The research was published in the journal Nature Medicine.