Patriotic: Sir Peter Wood has always voluntarily paid UK taxes on his self-generated wealth

Sir Peter Wood, one of Britain’s most successful businessmen, is not happy. He speaks from his Palm Beach villa, a short distance from Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago, where he is spending a few days relaxing in the United States after attending a board meeting of a Boston insurance company.

After that, he will return to the UK to vote, with a feeling of unease. He fears that Sir Keir Starmer’s Labor government could force him to leave the country, even though he has always voluntarily paid tax in the UK on his self-created wealth.

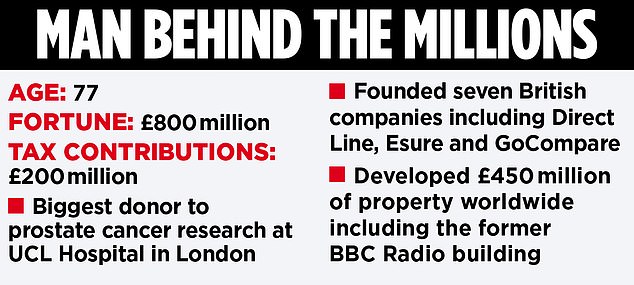

Wood set up three companies that were once part of the FTSE 350 – insurance firms Direct Line, Esure and GoCompare – and is proud to have always paid his taxes in his home country. Indeed, he has been at the top of the list of Britain’s top taxpayers for several years. His bills topped £200m when he sold businesses.

“I’ve been in the top ten for years,” Wood says. ‘I’m the kind of person who always pays my taxes in the UK. It’s the most patriotic thing to do.

Wood knows that his estate, which includes stakes in the Dignity funeral company and the Stanley Gibbons stamp auction house, will be hit by a 40 per cent inheritance tax, but he fears that the Labor Party, in a desperate attempt for tax revenue, is about to attack the rich again.

The businessman, who is spending five months at home in the United States and Spain, is therefore now thinking of protecting his assets abroad. Paradoxically, chemical industry billionaire and Manchester United shareholder Jim Ratcliffe, one of the wealthy people who has spoken out in favour of the Labour Party before the elections, opted a few years ago to transfer his personal tax status to Monaco.

Wood considers this the height of hypocrisy: “Jim Ratcliffe doesn’t pay any income tax in the UK. His companies do, but he personally doesn’t pay any tax. He now supports the Labor Party. That’s a bit exaggerated”.

Wood is not the only one who fears about Labour’s wealth taxes. A friend who is still working hard in the textile sector at 70 years old tells me that his son-in-law, a multimillionaire real estate magnate, decided a few months ago – in the midst of the expected increases in taxes on capital and wealth – to move his family and your tax domicile from Great Britain to Monaco. He was not prepared to see an empire, which owns some of the country’s most recognizable real estate assets, dismembered to pay taxes in the UK.

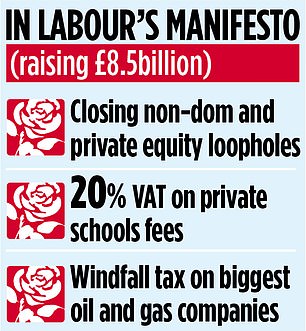

Star and shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves often talks about closing tax loopholes. This is shorthand for imposing new levies. Fear of what is to come is already boosting fortunes abroad. Thatcher’s revolution, which saw wealthy British exiles return to spending and investing, is in danger of being reversed. Labour’s ‘wealth creation’ electoral votes risk failing before taking office.

UK businessmen and super-rich fear attack. It’s tempting to say goodbye. But – if Labor is serious about boosting growth and restoring stability to economic policy – attacks on the wealthy can only curb spending, saving and investment.

The Labor Party is publicly taking aim at what it sees as privilege with a 20 per cent VAT tax on school fees. And North Sea oil exploration has been halted by plans to close so-called investment loopholes in an industry that already pays a headline tax rate of 75 percent. But Labor could do much more, as the fragility of the cost calculations in its manifesto and the gaping hole in the public finances have been revealed. The Institute for Fiscal Studies, an independent body, describes a “toxic mix” in public finances. Labour’s triple tax lock, which prohibits increases in VAT, income tax and national insurance contributions, requires Reeves to find other targets.

Plans have been announced to target the non-domiciled and private equity tycoons. His unannounced agenda is likely to include other goals. In 1997, when Labor inherited much more stable public finances, it financed new spending by taxing dividends paid to pension funds and electricity companies.

A popular suggestion this time is to tax capital at the same rate as income. Tax relief on contributions to pension funds may also risk discouraging already inadequate savings.

The changes initiated by Jeremy Hunt to the non-domicile regime have already caused many super-rich to pack their bags.

A source told me that in three years they will all be gone and a huge amount of money spent and invested in the UK will be gone forever.

Business leaders like Wood are exasperated.

“I paid taxes in the UK because I could afford it,” he says. One of Wood’s daughters is a prominent interior designer and adds: “Her business is in crisis because non-residents and top salespeople are fleeing the country.”

Britain faces a shortfall in public and private investment, essential for growth. Driving away our brightest entrepreneurial brains can only slow down recovery.