Table of Contents

Among the tens of thousands of words about Chelsea FC’s chaotic start to the Premier League season, there is one significant element missing from the raucous discussion.

Ownership is vitally important for football clubs, as it is for all businesses, whether supermarkets, department stores or advanced aerospace and engineering firms.

It is often presented to private equity firm owners and managers as a panacea for sclerotic and poorly managed publicly traded companies, and as a road map for amateur-run sports businesses.

The promoters seek to bring the magic of debt to a company and a firmer and more focused management of the underlying businesses.

In ruins: Chelsea FC’s Stamford Bridge stadium. The club’s new private equity owners have promised to spend up to $1 billion or more on improvements, but so far, little has been done.

There are notable commercial (if not consumer) successes, such as innovative fintech Worldpay, retailer Pets at Home and the change and value creation in F1 racing.

But there have been calamities too: Debenhams, Asda and care home provider Southern Cross Chelsea fell into private equity hands in May 2022.

The club had been confiscated by Her Majesty’s Treasury from Kremlin friend Roman Abramovich following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The new owners were a consortium of investors under the name BlueCo, led by Todd Boehly and funded largely by California-based Clearlake Capital. The group acquired the club for $3 billion (£2.4 billion).

Clearlake controlled 60 percent of the company and Boehly and his partners controlled 40 percent.

Boehly became the public face and has an equal stake in the club with Hansjorg Wyss and Mark Walter.

Boehly’s winning team triumphed on price and on the strength of his track record not only in managing but also in turning around troubled sports companies.

By the standards of his baseball team, the Los Angeles Dodgers, Chelsea was in very good health when Boehly took over.

But all private equity has brought to Chelsea is overly clever accounting.

To circumvent “fair play” rules that limit spending on transfers, Boehly and company have resorted to financial engineering.

Own goal: Todd Boehly leads group of investors who now own Chelsea FC

Instead of two-, three- or four-year contracts, players are on “long-term” contracts of six to nine years, allowing their value to depreciate over the course of the commitment.

This is a clever accounting statistic, but it also means that when mistakes are made, the players with the highest salaries are the hardest to move.

Instead, young lions born and raised in Chelsea are cannon fodder to be culled.

In 2021, under German coach Thomas Tuchel, the club won the world’s most coveted club trophy, beating superstars Manchester City to become European champions.

The future looked bright with the Boehly consortium promising to spend up to $1 billion or more on modernising or replacing Chelsea’s historic but sub-par stadium at Stamford Bridge.

So far, little has been done. The stairs are narrow, steep and difficult to reach. The bathrooms are unhygienic. It is the least impressive luxury club.

When the team was a reliable, trophy-winning outfit, the shortcomings were tolerable. And all this despite the fact that Stamford Bridge sits on one of the biggest and most valuable grounds in the country.

Abramovich had plans to invest £1bn or more in west London before being ostracised.

It’s easy to understand why so much faith was placed in Boehly and company. They turned the Dodgers from serial losers into World Series champions and developed a shiny new playing field.

They added UK business experience through property tycoon Jonathan Goldstein.

What could go wrong? Football is a notoriously fickle business, but generally a bottomless pit of money, stable ownership and skilled management and coaching yield trophies.

Marginalised: Hard-working, high-priced players like Raheem Sterling (pictured) are being humiliated and traded around like objects rather than people.

At Chelsea, the opposite has happened: a carefully constructed team of experienced and young players has been demolished and many of their best players are now at rival clubs.

Instead of assembling a well-functioning team, the private equity owners embarked on a bizarre accumulation of a long list of potential stars, whose names most fans can barely recognize.

A £1bn splurge has resulted in one of the biggest squads in football history, with 54 players (at last count), eight of them on loan.

Instead of stability, they have brought the volatility of hedge fund investors to the club. The owners treat their main assets, the enormous talent of the established stars, with contempt.

Hard-earned, acquired players like Raheem Sterling and future academy talents like Conor Gallagher are being humiliated and traded away like objects rather than people after their breakout season.

Keen to achieve rapid success, there is a third new manager in two years: Italian Enzo Maresca, 44, who arrived from Leicester City with no direct experience of managing in the Premier League or conquering Europe.

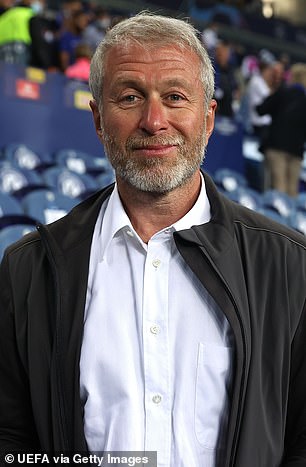

Former owner: Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich

He replaced Mauricio Pochettino, who left by mutual consent, after giving up sixth place in the 2023-24 season.

The patience of intelligent, long-standing supporters with a deep understanding of the game and football finances has been put to the test.

One of them, who has an acclaimed podcast, said she had “not turned on the TV for the first time in 20 years” for the season-opening game against Manchester City.

A lifelong fan and well-known lawyer and activist against racism in football wrote: “What a disaster.”

The rotation of players has left many fans asking for guidance for their own team from unknowns in the program rather than more easily identifiable visitors.

Football has become increasingly scientific, analytical and statistical. Teams such as Brighton and Brentford have employed brilliant techniques, which have far exceeded their spending power, stadium size and international support.

But that mathematical precision only works when combined with specialized training, brilliant psychology and leadership.

Some 2,550 private equity tycoons in the UK benefit from a tax loophole known as “carried interest”.

The industry defends itself by arguing that it employs millions of people and contributes enormously to the success of the City, but there is a tendency to sweep under the carpet the negative effects in terms of wasted jobs, an over-reliance on debt and an ability to circumvent good governance.

Chelsea shows the private equity scam at its worst, most culturally blind and indifferent.

It has offered the worst of both worlds: a financially driven franchise on a journey toward self-destruction.

DIY INVESTMENT PLATFORMS

AJ Bell

AJ Bell

Easy investment and ready-to-use portfolios

Hargreaves Lansdown

Hargreaves Lansdown

Free investment ideas and fund trading

interactive investor

interactive investor

Flat rate investing from £4.99 per month

Saxo

Saxo

Get £200 back in trading commissions

Trade 212

Trade 212

Free treatment and no commissions per account

Affiliate links: If you purchase a product This is Money may earn a commission. These offers are chosen by our editorial team as we believe they are worth highlighting. This does not affect our editorial independence.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. This helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationships to affect our editorial independence.