An experienced hiker who faced almost certain death after becoming stranded in a remote valley with no mobile phone signal has revealed the last-minute decision that saved his life.

Andy Collins, 59, embarked on a three-day, 47km ‘K2K’ walk from Kanangra Walls to his hometown of Katoomba in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales at the end of February.

The shepherd, who used to work for the National Parks and Wildlife Service, has done hundreds of similar hikes in the region and knows the terrain better than most.

But his wife Melissa still made him make a promise.

“She was a little worried that I would leave alone without any type of personal locator beacon (a device used in emergency situations to alert authorities to your exact coordinates), so I promised him I’d take one,” Collins told Daily Mail Australia.

It was a promise that ended up saving his life.

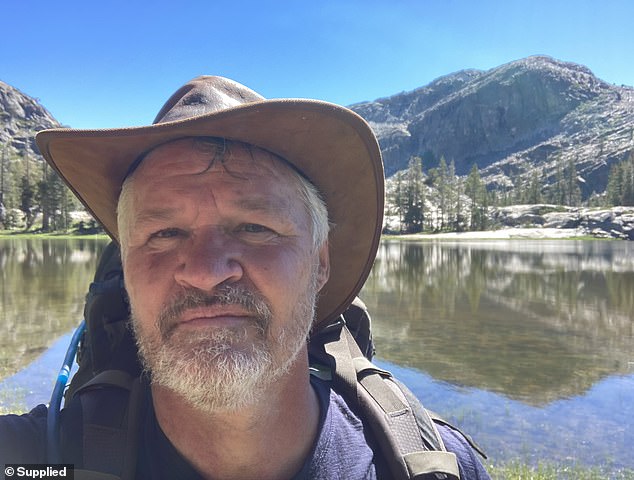

Andy Collins (pictured), 59, embarked on a three-day 47km walk from Kanangra Walls to his hometown of Katoomba in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales at the end of February.

The shepherd, who used to work for the National Parks and Wildlife Service, has done hundreds of similar hikes in the region and knows the terrain better than most.

Collins had researched the route and read everything he could find in recent trail reports to understand the conditions.

The wild 2019 bushfires and subsequent flooding have created a “perfect storm” of conditions for rapid regrowth of the bush, leaving many tracks completely overgrown.

But nothing he read worried him much, so his wife left him near the sandstone cliffs of Kanangra Walls on the afternoon of February 26.

After saying goodbye, he walked through the desert for several hours before camping for the night.

“The next day the trail was a little overgrown, but nothing I haven’t done before,” Collins said.

“I actually made really good time that day and I thought, ‘Oh yeah, this will be good.’

Early that afternoon, he reached Mount Cloudmaker, which is almost 1,170m high, before beginning a descent of 800m over about 5km to the Cox River.

“As I went further and further up the ridge, it got thicker and thicker with a lot of downed wood and a lot of regrowth,” Collins said.

‘There were vines and brambles from chest to head height and it was impossible to get through.

‘It was slow and very tiring. It wasn’t very hot and I had three and a half liters of water that I had been drinking all day.’

At dusk, Collins was still 200 meters above the Cox River and was forced to camp in the brush.

“I was exhausted,” Mr. Collins said.

“I ended up collapsing on the side of the hill and wrapping myself in my sleeping bag because there was nowhere to pitch my tent.”

Dawn came and it took Mr Collins more than two hours to make his way the remaining kilometer to the river bank.

“It was so overgrown that there was no sign of the runway,” he said.

When he finally reached the river, he drank two liters of water mixed with hydrolytes to try to stop the leg cramps.

At that point, I had planned to abandon the hike and walk out of the bush to the nearest available point.

“But suddenly I started to feel very bad. I was vomiting and passing water,’ she said.

‘I also began to suffer very severe pain in my back, which I dismissed as cramps. But then there came a point where I couldn’t move anymore.

What Mr. Collins didn’t know was that he was actually suffering from acute kidney failure caused by extremely strenuous exertion and dehydration.

The wild 2019 bushfires and subsequent flooding have created a “perfect storm” of conditions for rapid bush growth, leaving many tracks completely overgrown.

As the sun rose in the sky and his pain intensified, he began to panic.

He knew he needed to be out of the bush that night so he could attend his son’s graduation from the New South Wales Police Academy in Goulburn the next day.

Helpless, the only thing he could do was lie down in the river to cool off with a towel to protect his skin from the fierce sun.

With no signal on his phone and the temperature now over 40 degrees, he was left with only one option: activate the personal locator beacon (PLB).

“I was very sad to have to retire. I didn’t want to be a bother to people, but I realized that my body had completely shut down,” he said.

About 90 minutes later a PolAir helicopter arrived.

With no signal on his phone and the temperature now over 40 degrees, he was left with only one option: activate the personal locator beacon (PLB). A PolAir helicopter arrived 90 minutes later.

His rescuers found Mr Collins lying in the river trying to cool off with a towel to protect his skin from the strong sun (pictured).

Mr Collins suffered from acute kidney failure caused by extremely strenuous exertion and dehydration.

The police realized the trouble Mr Collins was in and sent an air ambulance.

He missed his son Ben’s graduation and spent five nights in the hospital, but in a delightful twist, the rescue helicopter pilot attended Ben’s graduation the next day.

Although Collins did not survive while recovering from acute kidney failure, his wife Melissa and son Ben were photographed with their savior.

“The paramedics said if they hadn’t put me through PLB, it would have been a full body recovery,” Collins said.

His only advice to his fellow hikers would be to always carry one with you, no matter how experienced you are.

‘They are very light and do not add anything to the weight of the backpack. As convenient as it is to have one, it’s crazy not to have one,” Mr Collins said.

GME, an Australian-owned security technology company, subsidizes the cost of PLBs to National Park Centers so hikers can rent them.

A PLB similar to the one Collins carried with him on his hike (pictured)

Collins missed his son’s graduation from the New South Wales Police Academy in Goulburn when he was forced to spend five nights in hospital recovering.

But in a delightful twist, the pilot who rescued him was present and had a photo taken with Mr Collins’ wife, Melissa, and son, Ben (pictured).

GME safety expert Tony Crooke said that if Collins had not taken one of the emergency beacons, “the outcome could have been very different.”

“He’s definitely not a keen hiker,” Mr Cooke said.

“He has a lot of experience and I guess the fact that he has so much experience he still saw fit to take a beacon in case something went wrong.”

“Ultimately, that was probably what saved his life.”

Cooke strongly recommended hikers also consider carrying a portable UHF CB radio to allow two-way communication with rescue authorities if they ever found themselves in trouble.

“Most people rely on their mobile phone as a communication device, which is great if you’re in a metropolitan area,” Cooke said.

“But if you are traveling to a regional or remote area, it is very important to remember that Less than 30 percent of Australia has mobile phone coverage.

“Something like a portable UHF CB radio, which is an open communications platform, will allow you to connect with others who can help you assess your situation and provide you with the help you need.”

Cooke said a PLB, which uses satellites to transmit its exact coordinates to rescue authorities, is a last resort.