Table of Contents

Whether you eat beef, lamb or even chicken, no Sunday roast is complete without a Yorkshire pudding.

Recently named Britain’s most prized regional delicacy, this delicious cup of cooked pastry may be the most difficult element of the dish to prepare.

Even chefs at top restaurants and expensive gastropubs have been known to mess them up.

And is there anything worse than a Yorkshire pudding that’s too flat, too dry or just plain stone cold?

To mark National Yorkshire Pudding Day today, MailOnline has provided a step-by-step guide to making the perfect Yorkie, according to science.

To mark National Yorkshire Pudding Day today, MailOnline has provided a step-by-step guide to making the perfect Yorkie, according to science.

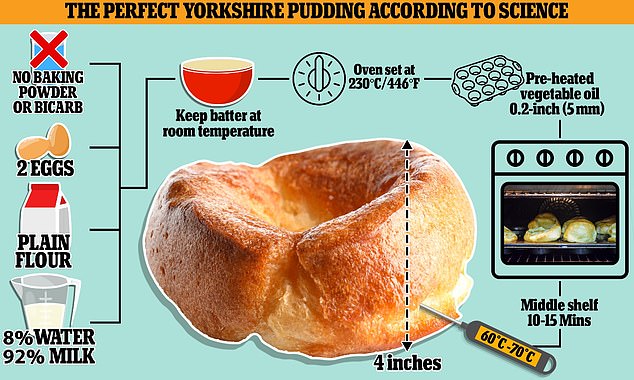

According to scientists at the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), a Yorkshire pudding recipe has just five ingredients: flour, milk, water, eggs and salt.

The RSC recipe strictly calls for all-purpose flour, not self-rising flour, to which baking powder is added.

In fact, you should not add any baking powder or baking soda to the mixture, because this can result in flatter, deflated puddings that have not risen properly.

“One of the theories is that they will make the dough rise too quickly before the gluten has time to strengthen the mixture and then it will collapse,” British food technologist and Yorkie fan Elizabeth Head told MailOnline.

Additionally, baking soda can make the dough too “doughy” or increase the risk of burning, according to RSC.

For the liquid, RSC says chefs should use 92 per cent milk and 8 per cent water, rather than just milk as is commonly done in the country’s kitchens.

The extra moisture from the water makes Yorkies lighter and bloated, because the movement of vapor created by the heat encourages them to swell upward.

No less important are the eggs, which also provide moisture and act as an emulsifier, allowing the ingredients to come together.

Two eggs should be enough for a batch of six puddings, along with 250ml of liquid (230ml milk and 20ml water), 85g plain flour and half a teaspoon of salt.

Once the dough is whipped to a thin, cream-like consistency, it should be kept at room temperature, not placed in the refrigerator.

Mrs Head told MailOnline: “The dough needs to be at room temperature so that when it comes into contact with the hot oil it rises better.”

‘When the dough hits the hot oil, it is easier for the oil to heat a room temperature dough than a very cold dough.

“A cold mixture won’t rise as well and you’ll end up with a dense pudding.”

Whether you eat beef, lamb or even chicken, no Sunday roast is complete without a Yorkshire pudding.

Following these steps correctly will result in Yorkshire puddings that are at least 10cm (4in) tall; shorter than that and are not technically Yorkshire puddings, the RSC claims.

One of the most important tips is not to open the oven door while Yorkies are cooking, as they could deflate in the cooler room temperature air, according to Ms Head.

Of course, the perfect Yorkshire pudding recipe will vary from chef to chef.

Heston Blumenthal, known for his scientific approach to cooking and gastronomy, published a recipe for the perfect Yorkshire pudding in his latest book, ‘Is This A Cookbook?’

She says “very hot oil” is the key to a great Yorkshire pudding, and opts for vegetable oil because it has a high smoke point (RSC suggests using beef for the same reason, while Mrs Head opts for lard pork).

The incredibly hot fat not only cooks the dough quickly, but it also provides a protective layer that helps prevent the dough from sticking to the pan, Blumenthal says.

Only 5mm (0.2in) of oil should be placed in each hole of a Yorkshire pudding tray before preheating to 230°C/446°F.

British chef Heston Blumenthal (pictured), known for his scientific approach to cooking, says the key to perfecting Yorkshire puddings is “very hot” oil

Once the oil is “very hot”, the batter should be poured in (a layer about one cm (0.4 in) deep per hole) and the tray should be placed on the center shelf of the oven.

“Avoid shaking the tray and mixing the oil and batter, which could result in greasy Yorkshire puddings,” says Blumenthal.

Although the top of the oven is the hottest place, the middle shelf is the best place for the puddings because they will probably have the most room to rise, he adds.

About 15 minutes in the oven should be enough, or until they are nicely browned and puffed up as much as possible.

As an optional bold extra, chefs can add a tablespoon of English mustard to the batter for a more intensely flavored pudding, suggests Blumenthal.

Like many of Britain’s most prized dishes, the exact origins of the Yorkie are unclear, although the consensus is that it was always associated with the north of England.

According to Hazel Flight, a nutritionist at Edge Hill University in Lancashire, the dish was originally known simply as “batter” or “dripping pudding”.

The prefix ‘Yorkshire’ was first added in 1747, in the best-selling cookery book ‘The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Simple’ by cookery writer Hannah Glasse, a Londoner.

Back then, it was always served as a separate dish before the main meal, usually with sauce made from the roast juice.

The first appearance of ‘Yorkshire pudding’ comes from the 1747 book ‘The Art of Cooking Made Simple and Easy’ by Hannah Glasse (pictured).

Yorkshire housewives served Yorkshire pudding before the meal so they could eat less of the more expensive main course.

As to why it was called “pudding” in the first place, originally puddings were not always supposed to be sweet as we know them today.

The word “pudding” comes from the French word “boudin”, which in turn comes from the Latin “botellus”, both words for small sausages.

In medieval England, the use of the word “pudding” probably referred to the sausage when it came in batter.

But in subsequent years, the name “pudding” remained even in the absence of meat.