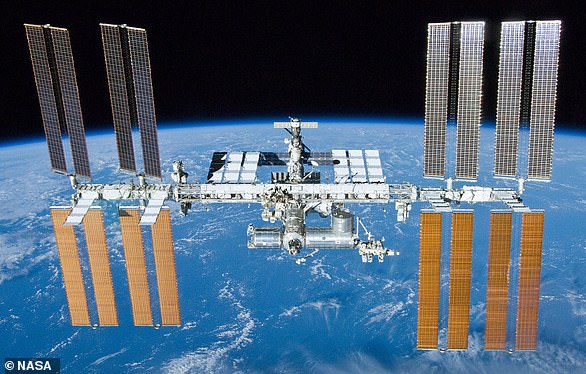

A space capsule containing a small unmanned pharmaceutical plant floated into the Utah desert in February of this year carrying freshly made crystals of anti-HIV medication.

The orbital platform was the culmination of four years of work by a California-based startup, Varda, which hopes to use the unique microgravity conditions in low-Earth orbit to make purer, and therefore cheaper, medicines.

Like the strange shape that ice cubes can take in an unbalanced ice bucket, a drug maker’s tiny molecular-scale chemical reactions can lead to unbalanced and unwanted shapes due solely to the bias of the Earth’s gravitational pull.

But Varda is not the only company entering the Big Pharma space race in an effort to improve these conditions to create its crystalline drug molecules.

Pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly and a number of universities that have partnered with the International Space Station National Laboratory have also begun testing orbital platforms for everything from cancer drugs to Alzheimer’s disease research.

A space capsule containing a small unmanned pharmaceutical plant (above) floated into the Utah desert in February of this year carrying freshly made crystals of anti-HIV drugs.

The orbital platform was the culmination of four years of work by a new El Segundo, California-based company, Varda Space Industries, which hopes to use the unique microgravity conditions in low-Earth orbit to make purer medicines and, therefore, cheaper.

“The impact of microgravity appears to be very effective in obtaining pure crystalline materials that have unique properties,” said biochemistry professor Anne Wilson of Butler University. the Wall Street Journal this week.

Wilson, who has conducted research on the chemistry of crystallization in microgravity but has no direct affiliation with Varda, noted that the promise of microgravity includes improved molecular structures for a host of specialty materials, in and out of medicine.

According to the company’s chief scientific officer, Adrian Radocea, Varda is currently analyzing the results of its HIV drug production trial in space.

Varda is now preparing for two future flights, launching this year starting in June or July aboard a reusable SpaceX rocket, according to Varda co-founder and president Delian Asparouhov.

Asparouhov said his company has already signed contracts with pharmaceutical companies for this year’s flights, as well as three more scheduled for 2025, some of whose names will be revealed ahead of this summer’s launch.

The project, which manufactured the drug ritonavir, was launched in June 2023.

The company is now preparing for two future flights, launching this year starting in June or July aboard a reusable SpaceX rocket, according to Varda co-founder and president Delian Asparouhov.

Asparouhov told the Journal that his company has already signed contracts with pharmaceutical companies for this year’s flights, as well as three more scheduled for 2025, some of whose names will be revealed before this summer’s launch.

But the space drug startup also has a more terrestrial program to help pharmaceutical companies determine whether their drugs would particularly benefit from the elaborate microgravity manufacturing process in orbit.

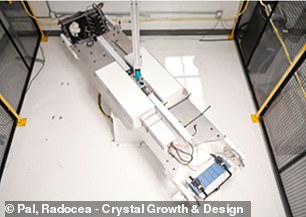

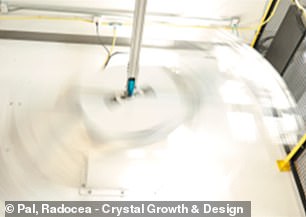

A new paper by two Varda researchers, published Thursday in the journal Crystal Growth and Designused a ground centrifuge to track which crystalline drug molecules are most sensitive to gravitational forces.

The company’s scientists called the proof of concept a “hypergravity crystallization platform,” which they plan to offer to potential pharmaceutical clients as a convenient screening tool for how their own drugs respond to gravity.

For their peer-reviewed test, Varda researcher Kanjakha Pal and his CSO Radocea used the essential amino acid L-histidine, which has unique properties based on its shape and has been used to preserve organs before transplant surgeries.

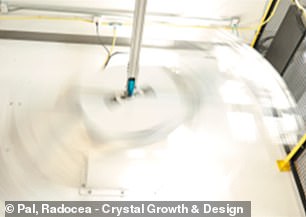

A new paper by two Varda researchers, published Thursday in the journal Crystal Growth & Design, used a ground centrifuge (above) to track which drug molecules with a crystalline structure are most sensitive to gravitational forces.

“Hypergravity experiments,” wrote Pal and Radocea, “show that gravity affects the crystallization process even when the solution is stirred at high revolutions (in a centrifuge).”

The result, they said, highlighted “that gravity likely plays an important role in many small molecule crystallization processes.”

“If you can observe a trend, it is much easier to convince the scientific public,” Radocea told the Journal.

Varda researchers hope to conduct more experiments to differentiate what other factors, such as cosmic radiation, might affect chemical reactions in low-Earth orbit.

“The ideal,” as Varda co-founder and investor Josh Wolfe put it, “is to reduce the cost of very expensive, life-saving drugs.”