When Beata Halassy discovered that her stage 3 breast cancer had returned despite having a mastectomy, she couldn’t bring herself to undergo another brutal round of chemotherapy.

The expert infectious disease researcher, now 53, decided to take matters into her own hands and used her decades of experience in virology to inject a virus directly into the tumor in her breast.

Despite possible side effects, such as a blood clot in the lungs, loss of blood supply to the ovaries and fever, it used a measles virus and a pathogen that causes flu-like symptoms, which attacked the tumor and triggered a turbocharged immune response to kill. of cancer cells.

Miraculously, the tumor shrank without invading the pectoral muscle or skin, and he has now been cancer-free for four years.

The success of the treatment raises ethical questions that Dr. Halassy and other virus experts must confront.

The problem is not so much that Dr. Halassy has chosen an unconventional treatment path.

The potential damage comes from publishing their brilliant results in the journal. Vaccines which experts fear could lead to imitators without adequate experience.

She writes: “The short- and medium-term outcome of this unconventional treatment, which lacked significant toxicity, was undoubtedly beneficial.”

Dr. Beata Halassy developed viruses in her laboratory that she injected directly into her breast tumor. The tumor shrank and detached from the pectoral muscle, allowing doctors to remove it more easily.

in the diary NatureA study on Dr. Halassy’s treatment concludes that “self-medication with oncolytic viruses should not be the first approach to treating diagnosed cancer.”

Her last bout of breast cancer in 2020 It was stage three.which is considered advanced and with a high probability of spreading to other parts of the body.

The experimental treatment she tried is called oncolytic virotherapy (OVT) and she has been cancer-free for four years.

The experimental viral therapy that Dr. Halassy designed for herself in her laboratory at the University of Zagreb in Croatia is usually reserved for cancer patients who have tried several rounds of chemotherapy and radiation and have run out of options.

Patients with advanced cancer often have weaker immune systems than healthy people, an effect of chemotherapy and radiation treatments.

OVT directly destroys cancer cells, compensating for their weaker than normal immune response to cancer cells.

OVT is experimental, but the potential benefits outweigh the risks for many people.

It is unknown how many people are taking this medical route. Still, an estimated 623,405 have breast, prostate, lung, colorectal, melanoma or bladder cancer that has spread to other parts of the body and has entered stage four or five. Those people could potentially benefit from OVT.

Federal health regulators have approved only one type of OVT and it is designed to treat metastatic melanoma. However, there have been no approved treatments for breast cancer.

Dr. Halassy’s app has not been approved for widespread use

After preparing the measles virus and the influenza-like virus VSV in his lab, a colleague injected them directly into his tumor for two months.

Oncologists were watching her closely, ready to start a regimen of a common anti-cancer drug (not chemotherapy) called trastuzumab if something went wrong.

But they didn’t need to use it until those two months were up, a period during which the viruses stimulated the immune system to destroy cancer cells.

Dr Halassy said: “An immune response was surely provoked.”

The treatment shrank the tumor and detached it from the pectoral muscle it had attached to, allowing doctors to remove it more easily. He then continued trastuzumab for about a year.

Dr. Halassy tried for years to get her findings published in medical journals, but received rejection after rejection.

She said: “The main concern was always the ethical issues.”

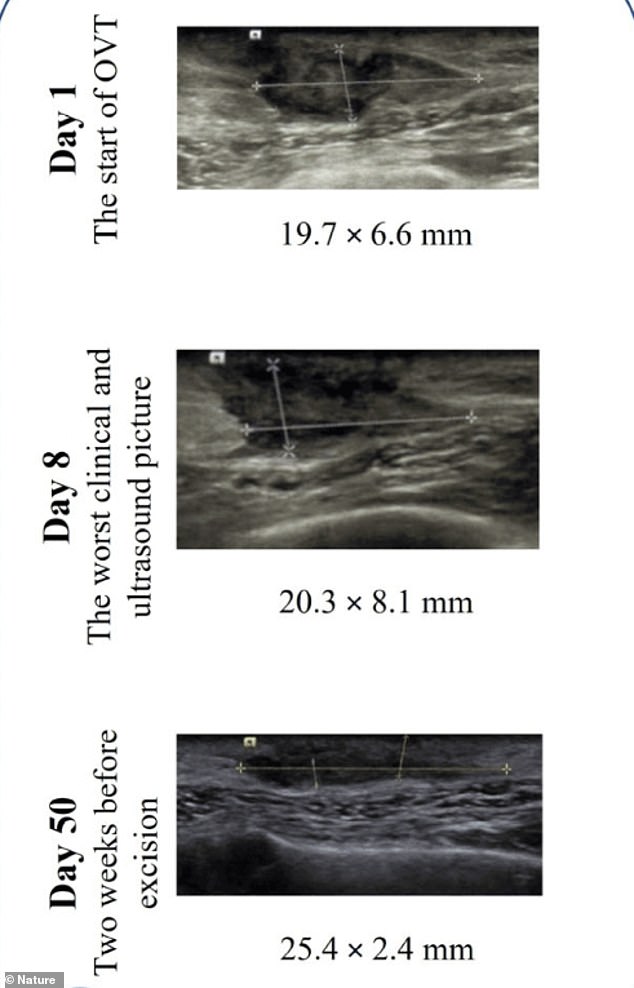

The three panels show that the tumor (measured by the two perpendicular lines) shrinks over time, making it easier to remove surgically.

Injecting the virus directly into the tumor triggered a strong immune response that helped shrink the tumor. The immune system recognizes tumor cells infected by the virus as foreign and begins to attack them.

Dr. Halassy had spent years studying viruses. While he is not an OVT specialist, his career growing and purifying viruses in his laboratory gave him the confidence to try it.

However, oncologists and other researchers say this approach is dangerous for the layman with cancer, who might be more inclined to try an experimental treatment. Experts tend to agree on the saying, “Don’t try this at home.”

Jacob Sherkow, a law and medicine researcher at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who specializes in medical ethics, said he would have preferred to see a discussion of the ethical implications alongside the case report to provide more depth on the topic.

He added: “I think ultimately it falls within the line of being ethical, but it’s not a closed case.”