The richest man in Britain and by far the most unpleasant.

Not Hugh, the seventh Duke of Westminster, who is marrying in grand style at Chester Cathedral next month, but his great-uncle Bendor, the second Duke.

According to one biographer, he was “a jealous womanizing bully,” a man who only cared about getting even richer and having a good time at the expense of others.

Such was his sense of entitlement that he was prepared to divorce his wife at the drop of a hat, just because she had read a book.

And he plotted to have his brother-in-law, the liberal politician Earl Beauchamp, expelled from Britain because he was secretly gay.

The distraught earl, who had been a key part of King George V’s inner circle, was on the brink of suicide.

Beauchamp’s escape from Britain inspired Evelyn Waugh to write her iconic novel Brideshead Revisited.

The richest man in Britain and by far the most unpleasant. Not Hugh, the Duke of Westminster, who is marrying in grand style at Chester Cathedral next month, but his great-uncle Bendor.

Hugh, godson of King Charles and best friend of Prince William, is a generous-hearted soul whose charitable activities include supporting vulnerable children and young people.

Bendor’s great-nephew Hugh, godson of King Charles and best friend of Prince William, is a million miles from his ancestor in every possible way.

Her charitable activities include supporting vulnerable children and young people, working with organizations that support families, schools and local communities, and leading a fundraising campaign for the National Rehabilitation and Advocacy Centre.

And in his role as executive director of Family Action, he works with children from families affected by poverty, addiction, food insecurity, poor physical and mental health, poor housing, and domestic violence.

Bendor, whose real name was also Hugh, got his nickname from the family’s Derby-winning racehorse Bend Or.

He sailed on yachts and slept with women and was born into everything he could want.

But, according to a family member, he was an “angry, dissatisfied man, nothing more than an aging, spoiled, fatuous playboy.”

And he was a man accused of cruelly hastening the death of his only five-year-old son and heir.

The duke loved to hate people. He especially hated his sister’s husband.

Bendor was deeply jealous of Beauchamp’s closeness to the throne in his roles as Knight of the Garter and Lord Steward of the Household.

Although he had all the riches, he had no Garter. So he launched his plot to arrest and expel from Britain Beauchamp, who had a colorful homosexual life despite a happy marriage and seven children.

“Dear father-in-law,” he wrote, after having succeeded in his treacherous mission, “you got what you deserved!”

Bendor plotted to have his brother-in-law, the liberal politician Earl Beauchamp (above), expelled from Britain because he was secretly gay.

Earl Beauchamp became the inspiration for Evelyn Waugh’s character, Lord Marchmain, in her famous novel Brideshead Revisited. Above: Anthony Andrews, Laurence Olivier and Jeremy Irons as Lord Sebastian Flyte, Lord Marchmain and Charles Ryder in the 1981 television adaptation of Waugh’s novel.

Bendor, 2nd Duke of Westminster, with his fiancée Loelia Ponsonby in February 1930. The couple married a week later.

Constance ‘Shelagh’ Edwina Lewes was the first wife of Hugh Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster

The character of Lord Marchmain is based on the refugee earl, and Brideshead Castle is a portrait, in part, of the Beauchamp family home, Madresfield.

So what made the Duke so brute?

Born into colossal wealth (the family owned large tracts of London’s Belgravia and Mayfair), by the age of 20 he was already known as one of the richest men in the world.

He had a 10-year affair with fashion queen Coco Chanel before marrying several wives, four in total.

Bendor could have what – and who – he wanted.

That included not one, but two private yachts and a fleet of 17 Rolls Royces that followed him around the world wherever he went.

He had a personal train built to take him from the family estate, Eaton Hall in Cheshire, to London, where his main home was Grosvenor House in Grosvenor Square, later the site of the American Embassy.

“He was a man who liked to hide diamonds under his lovers’ pillows, and there were many, many lovers,” one biographer recalled.

But Bendor’s affection came at a price, a very high price. His third wife, Loelia Ponsonby, did not hold back when she wrote about him after his divorce.

“He got drunk every night,” he recalled. “The scenes of violence continued into the long hours of the night; objects flew through the air.”

Convinced that Loelia was cheating on him (who could blame her?), the Duke smashed his priceless Cartier diamond watch into pieces, then sifted through the rubble to collect and store the diamonds so she wouldn’t have them.

“Despite all his marriages, he produced only one male heir: Edward, Earl Grosvenor,” wrote biographer Jane Mulvagh.

‘When Edward was only five years old, his father insisted that he go hunting, despite the boy’s complaints of severe stomach pains. Edward died of peritonitis while in the hunting field that day.

Bendor’s wife instantly abandoned him and it was then that he directed his unsuppressed anger towards the unsuspecting Beauchamp, who had married his sister some years earlier.

Lettice, the wife of Earl Beauchamp, sister of the 2nd Duke of Westminster, with her three eldest daughters, Lettice, Sybil and Mary.

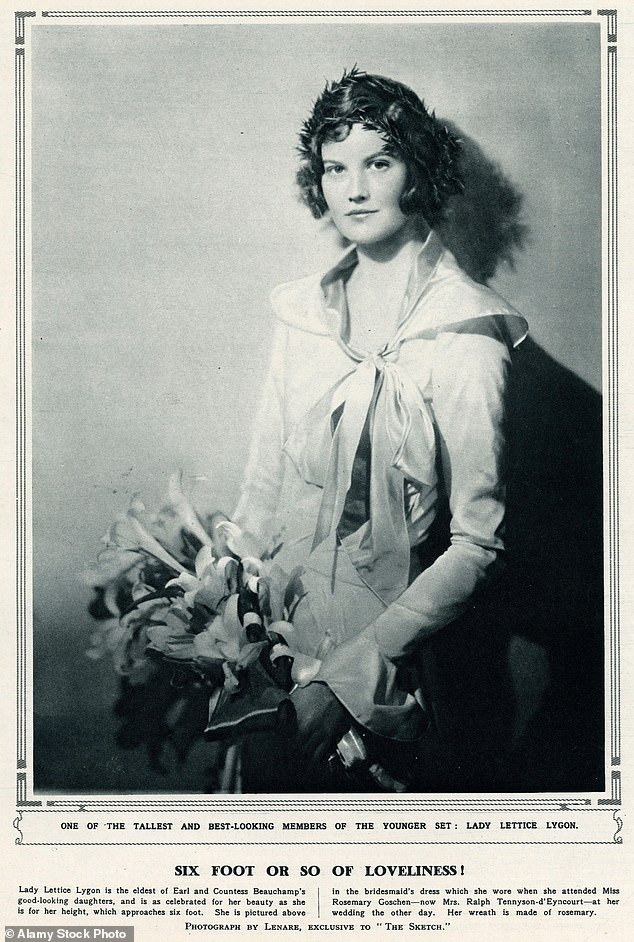

Lady Lettice Lygon was the eldest daughter of Earl Beauchamp. She appears in the photo above in The Sketch in 1929. The publication described the tall beauty as “about six feet of loveliness.”

Setting out to find him, Bendor let King George V know that his precious courtier had broken every rule in the book.

The king apparently blurted out upon hearing the news: “I thought men like that shot themselves.”

It was a ridiculous answer. But Beauchamp had ignored the rules of discretion that governed the upper classes, and just as an arrest warrant was about to be issued (homosexuality was still illegal), he issued a statement saying that his “poor health” had forced him to take a spa. cure in Germany.

He fled the country. It was then that Westminster sent his scathing and triumphant letter to his brother-in-law.

Beauchamp was helpless, his position and position in society ruined. But his seven children, all of whom adored him, dissuaded him from taking his life.

In exile for more than five years, he yearned daily for his beautiful home.

But when the dust finally settled over the scandal and he was allowed to return to Britain, he had just two years to live.

“The problem with Bendor was that he had too much money and not enough self-control,” wrote a friend after the duke’s death in 1953.