Australia is home to more than 350 species of native mammals, 87 percent of which are found nowhere else on Earth.

But with 39 of these species already extinct and another 110 listed as threatened, there’s a good chance many will be gone before you even know they exist. So here’s one we think you simply should know (and save) before it’s too late.

The charismatic kowari is a small carnivorous marsupial.

It was once common in the interior, but is now found only in the remote deserts of southwestern Queensland and northeastern South Australia, in less than 20 percent of its former range.

This pint-sized predator fits in the palm of your hand. His bright eyes, bushy tail and big personality make him the perfect example of outback Australia.

But with only 1,200 kowari in the wild, the federal government upgraded their conservation status in November from vulnerable to endangered.

Reversing the decline of the kowari is within our reach. But we need public support and political will to achieve it. It requires limiting cattle and sheep grazing while keeping feral cat numbers under control.

The kowari, a native marsupial found in outback Australia, was recently upgraded to endangered status, courtesy largely of feral cats.

The kowari (Dasyuroides byrnei) is a skilled hunter, stalking mice, tarantulas, moths, scorpions and even birds. Alert and efficient, they voraciously attack their prey.

Formerly known as the brush-tailed marsupial rat or Byrne’s crested-tailed marsupial rat, the kowari is most closely related to the Tasmanian devil and quolls.

The Wangkangurru Yarluyandi people use the name kowari, while the Dieri and Ngameni people use the similar-sounding name kariri.

The Kowaris live in rocky deserts. They mainly inhabit remote, treeless plains. These areas of flat, interlocking red pebbles form vast pavements that could be mistaken for the surface of Mars.

In the interior, where temperatures can exceed 50°C, kowaris combat the heat by taking refuge in burrows dug into mounds of sand. At night they emerge to run across the plains, head and distinctive tail held high, stopping regularly to search for predators and prey.

During cold winter days, kowaris slow down their metabolism to conserve energy. They enter a state of torpor, which is a daily version of hibernation.

At the two main sites in southern Australia, the number of animals captured in trapping studies decreased by 85% between 2000 and 2015. At this rate, the species could disappear from the area within two decades.

It is estimated that the entire population amounts to only 1,200 individuals spread over just 350 square kilometers. That’s a combined area of less than 20 km x 20 km.

Based on this evidence, the kowari’s conservation status was upgraded from vulnerable to endangered in November last year.

Kowaris have been declining for a while, but suddenly find themselves on the fast track to extinction. How can that be, when they live in one of the vastest and most remote areas of Australia?

Threats include land degradation due to grazing and predation by introduced feral cats and foxes.

But it is complicated. Threats can be combined to have a synergistic effect (greater than the sum of their parts). And then there are climatic influences.

Heavy rains in the desert trigger a cascade of events that culminate in an explosion in feral cat numbers.

When conditions dry out again, cats switch to eating larger or more difficult prey, such as bilbies and kowaris, often causing local extinctions. In southwestern Queensland, feral cats most likely wiped out one kowari population and decimated another.

Feral cats are a big problem for the Kowari (one appears in the photo after hunting a native marsupial)

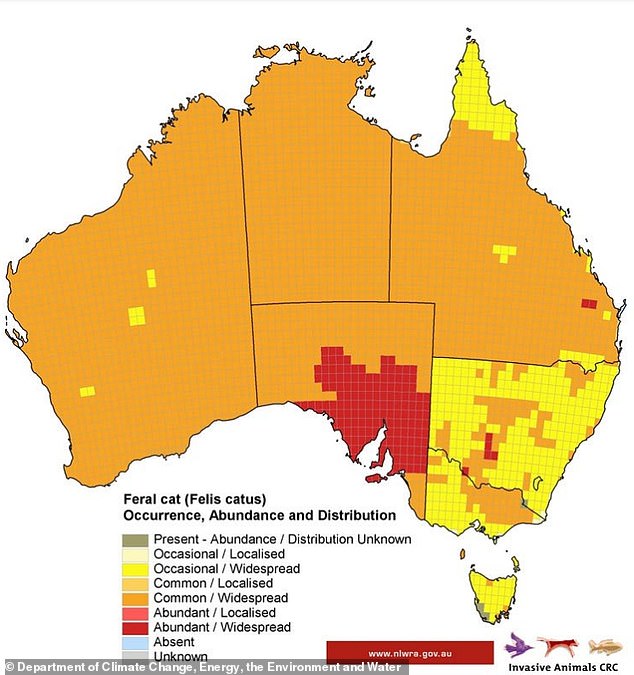

This map shows the distribution of millions of feral cats in Australia. They are more common in the interior and abundant in parts of South Africa.

Huge efforts to control cat infestations have so far saved kowari and bilby populations in Astrebla Downs National Park from local extinction, but other areas have succumbed.

In South Africa, all remaining kowari populations are found on grazing stations used for livestock grazing.

Cattle can trample kowari burrows. They can also compact sand mounds, making it difficult for kowaris to build burrows. And they eat the plants in the mounds, reducing the availability of both food and shelter. This makes the kowaris easy prey.

In recent decades, grazing has intensified. Almost half of Australia (44%) is covered by grazing leases where many threatened species are found.

Domestic livestock often graze near watering points, such as wells and troughs. More and more watering points are being established so that livestock can access more of the grazing pasture. So the area protected from grazing is shrinking as cattle increasingly encroach on Kowari territory.

We have the knowledge and tools necessary to save this species from extinction. We just need decisive leadership and sufficient funding to put these plans into action.

State governments should provide more resources for desert parks so that rangers can monitor feral cat numbers and respond quickly to pests. We can make use of new technologies, such as remote camera traps controlled via satellite. These measures would also protect the last remaining holdout of the bilby in Queensland, another nationally threatened mammal.

The pastoral industry and governments must work together to review the location of water points and reduce grazing pressure on known Kowari habitat.

By closing some watering points for pastoralists and ensuring that a portion of each lease (possibly 20%) is out of water, we can reduce damage to populations and provide refuge for threatened species. Pastoral businesses could show leadership and implement these actions themselves rather than waiting for governments to act.

In the meantime, reintroduction into safe havens is an interim measure that helps prevent the kowari’s imminent extinction. In 2022, 12 kowaris were successfully reintroduced to the 123 square kilometer fenced Arid Recovery Reserve in northern South Africa.

The population has increased since its release. The removal of cats, foxes and domestic animals from the reserve has given the Kowaris the opportunity to recover a small part of their former habitat.

But safe havens are small and we must act on a larger scale. If we don’t, the kowari may become another lost Australian species before you even see it.