A remarkable cache of love letters from Albert Einstein to his first wife revealing his bawdy side has gone on sale for £1 million.

The mathematical genius told Mileva Maric in a surprising letter that he couldn’t wait for her to visit him at Lake Como so they could “wrap themselves in his robe together.”

It is believed that she became pregnant during her subsequent stay in Italy and gave birth to her daughter Lieserl in early 1902.

Einstein also provided glimpses of his ingenious thinking when discussing his early academic career in the collection of 43 letters dating from 1898 to 1903.

In a letter he wrote: “My musings about radiation are beginning to take somewhat firmer ground.”

In another he stated: “I am increasingly convinced that the electrodynamics of bodies in motion, as presented today, is not correct and that it should be possible to present it in a simpler way.”

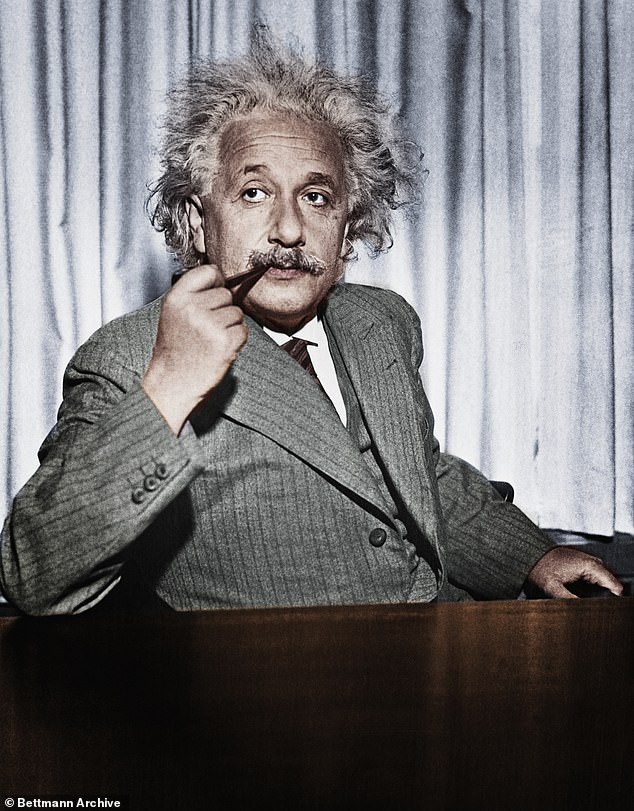

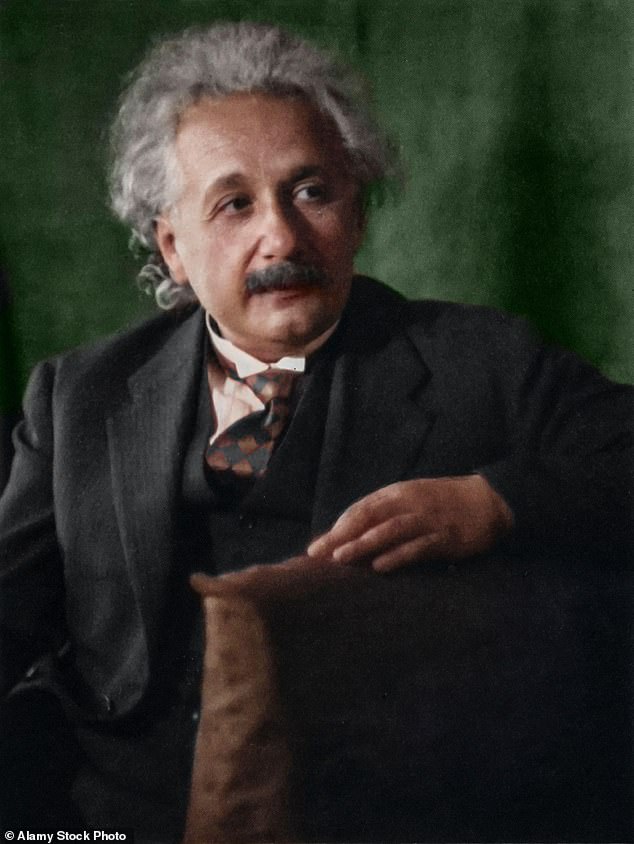

A remarkable cache of love letters from Albert Einstein (pictured) to his first wife revealing his raunchy side has gone on sale for £1 million.

In April 1901 he told Mileva (pictured, left) of his excitement over his impending visit to Lake Como, writing suggestively: “Come to Como and bring me my blue dressing gown, in which we can wrap ourselves.”

The mathematical genius tells Mileva Maric in a letter that he can’t wait for her to visit him on Lake Como so they can “wrap themselves in his robe together.”

He expanded on this theory in his groundbreaking 1905 paper on special relativity.

The letters to his “doll”, signed “Albert” and written in an old German Gothic style, will spark a bidding war at London’s Christie’s auction house.

Einstein was a 16-year-old student at the Zurich Polytechnic in Switzerland when he met Mileva, one of the first students in the physics and mathematics course.

Mileva, who was Serbian, was three years older than Einstein and her first letters in 1898 were quite formal.

As time passed, the letters reveal that their relationship became personal, to the disapproval of Einstein’s family.

Einstein confided to Mileva that his mother had told him: “You are ruining your future… That woman cannot enter a decent family.”

But Einstein, displaying his stubborn streak, ignored her pleas and, in early 1901, applied for teaching positions so he could earn enough money to marry Mileva.

In April 1901, he told Mileva of his excitement over his impending visit to Lake Como, writing suggestively: “Come to Como and bring me my blue dressing gown, in which we can wrap ourselves.”

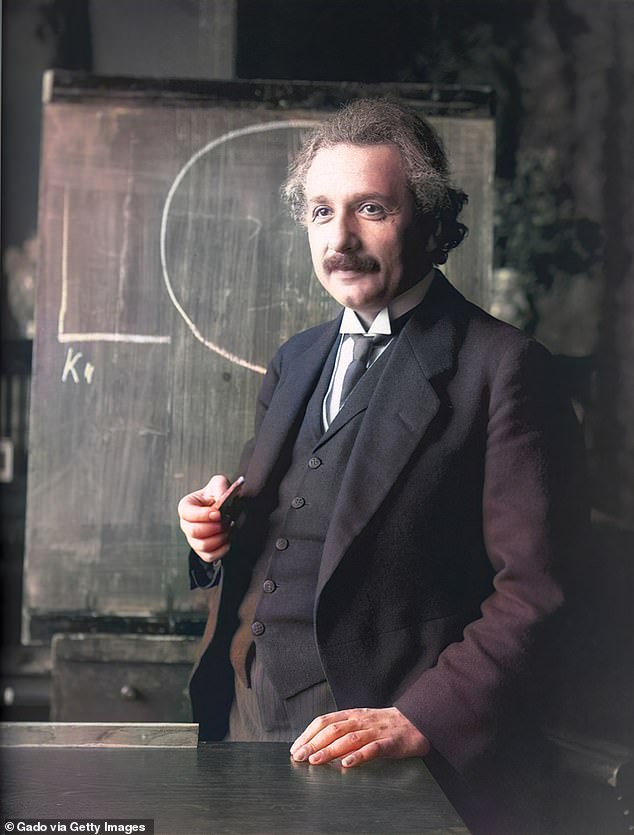

Einstein provided glimpses of his ingenious thinking as he discussed his early academic career in the collection of 43 letters dating from 1898 to 1903.

Einstein was a 16-year-old student at the Zurich Polytechnic in Switzerland when he met Mileva, one of the first students in the physics and mathematics course.

In a letter from October of that year, Einstein shared his excitement about impending fatherhood and referred to his unborn baby as Lieserl.

Mileva gave birth to her daughter in 1902, when Einstein was settled in Bern and waiting to begin his work at the Patent Office.

On February 4, 1902 he wrote proudly: “You see, it really turned out to be a Lieserl, just as you wanted.”

‘Is she healthy and already crying properly?

‘What kind of eyes does she have? Which of the two of us is he most like?

Einstein and Mileva married in January 1903 and the last letter refers to her second pregnancy, a son named Hans Albert.

He also mentions that Leiserl had been ill with scarlet fever, which tragically is believed to have killed her soon after.

Einstein and Mileva had a third son, Eduard, in 1910, but divorced in 1919 after she learned that he had been unfaithful to her cousin, Elsa Lowenthal.

Two years later he received the Nobel Prize in Physics and, as agreed in the divorce settlement, gave Mileva his prize.

The letters remained in the family until they were sold at auction in 1996, where the seller acquired them.

Auctioneers say it is extremely rare to find Einstein’s correspondence from before 1905 that reveals so much about his “training” years.

Thomas Venning, Christie’s manuscript specialist, said: “The letters give a full picture of what Albert Einstein was like in his formative years.

‘It is very rare to find letters from him before 1905 and for it to be such significant correspondence, addressed to such an important recipient, is simply wonderful.

‘Although he was only a teenager when he started writing them, it feels like he was already asking questions about different areas of physics.

“He didn’t just accept previous scientific thinking, he wanted to push boundaries and challenge conventions.”

Einstein died in 1955.

The sale will take place on December 11.