Ever since humans began looking up at the stars, we have been fascinated by the search for life beyond Earth.

But that search could soon be over, as scientists have discovered a planet that could be our “best bet” for finding alien life in the cosmos.

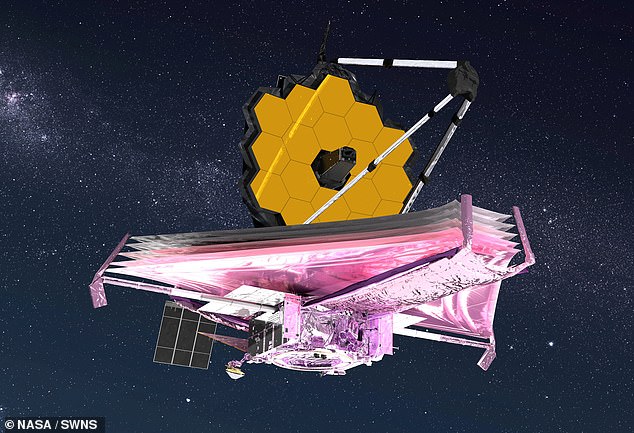

An international team of scientists used observations from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to analyze the atmosphere of an exoplanet called LHS 1140 b.

Their observations confirmed that the nearby planet could have an ocean of liquid water and even a nitrogen-rich atmosphere, like Earth.

Lead author Charles Cadieux of the University of Montreal said: “Of all the temperate exoplanets currently known, LHS 1140 b may well be our best bet for one day indirectly confirming the existence of liquid water on the surface of an alien world beyond our solar system.”

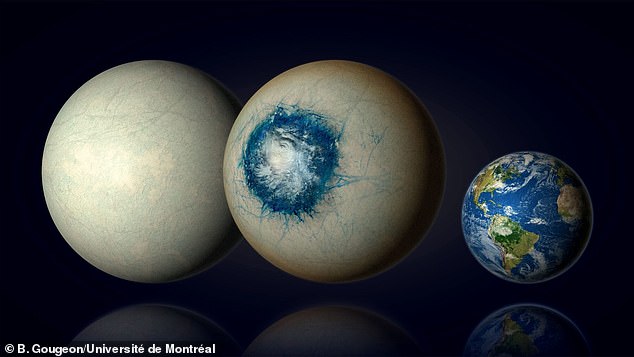

Scientists have discovered a distant exoplanet (pictured) that could be our best bet for finding extraterrestrial life.

Although we don’t know exactly what alien life would be like, scientists are almost certain that it would need liquid water to survive.

The exoplanet LHS 1140 b is located 48 light years from Earth in the constellation Cetus.

This makes it our closest neighboring planet that lies within its star’s “Goldilocks zone” – the region where water can exist in a liquid state.

This exoplanet is about six times the mass of Earth and orbits a small red dwarf star about one-fifth the size of our Sun, at a distance cool enough for water to potentially form.

Recent analysis suggested that the exoplanet was significantly less massive than an object of its size should be.

This left researchers with two options: either LHS 1140 b was a “mini-Neptune” composed mostly of swirling gas, or it was a “Mega-Earth” covered in liquid or frozen water.

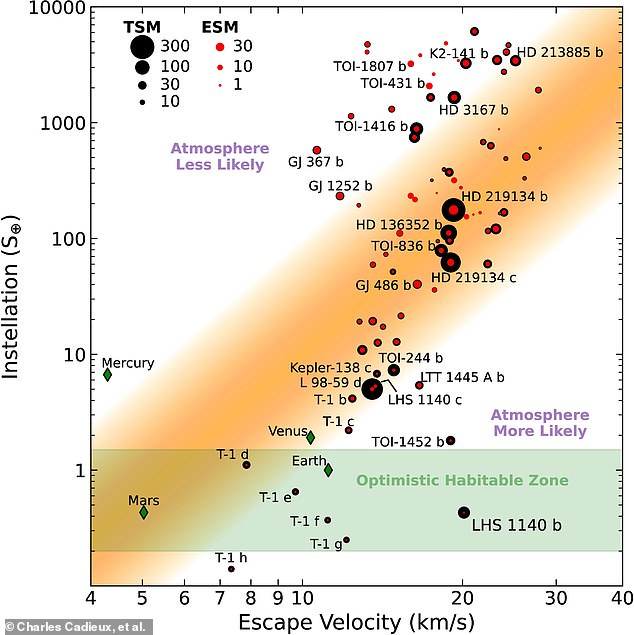

The exoplanet LHS 1140 b lies within its star’s habitable zone, the region where liquid water can exist. Its large mass also gives it a high enough outflow velocity to accumulate a thick atmosphere, as shown in this planet diagram.

To determine which was the case, researchers combined data from JWST and other space telescopes such as Hubble and Spitzer to perform the first “spectroscopic” analysis of LHS 1140 b.

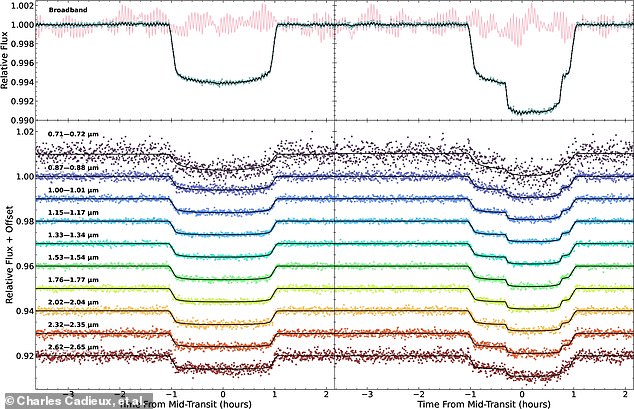

Since certain molecules block different wavelengths of light, by measuring the frequencies of light passing through the planet we can tell what chemicals may be present.

Their analysis suggests that LHS 1140 b is much more likely to be a “water world” or “snowball” with a rocky core rather than a gaseous mini-Neptune.

Even more exciting is that initial analysis suggests the exoplanet might even have a thick atmosphere like we have here on Earth.

That would give it a much greater capacity to retain heat from its star and make it more likely to have a stable climate, all important factors for the existence of life.

Like Earth (pictured), this exoplanet could have a thick, nitrogen-rich atmosphere that would act as an insulating blanket for the formation of liquid water.

Dr Ryan MacDonald, an astronomer at the University of Michigan who worked on the paper, says: “This is the first time we’ve seen a hint of an atmosphere on a rocky or ice-rich exoplanet with a habitable zone.”

Although they caution that more JWST observations are needed, the atmosphere could be rich in nitrogen, which makes up 78 percent of Earth’s atmosphere.

Dr Macdonald adds: “LHS 1140 b is one of the best small exoplanets in the habitable zone capable of supporting a thick atmosphere, and we may have found evidence of air on this world.”

Like the Moon’s orbit around Earth, LHS 1140 b has a synchronous orbit, meaning one side is permanently facing away from its star.

Although researchers believe the exoplanet is likely a frozen “snowball,” this means there could be liquid water on the side heated by the star.

To learn more about the exoplanet’s atmosphere, researchers are using data collected by the James Webb Space Telescope (pictured) in 2023.

Since certain molecules block different wavelengths of light, researchers were able to analyze the light passing through the exoplanet to determine what chemicals might be present. This diagram shows the spectrum of light collected from LHS 1140 b

If LHS 1140 b has an atmosphere, it likely has a “Bullseye Ocean” about 2,400 miles (4,000 km) in diameter, equivalent to half the surface of the Atlantic Ocean.

And the surface temperature of this ocean could be a pleasant 20°C (68°F), which is at the upper end of what sea temperatures around the UK reach in summer.

While this is not the first planet to be discovered within the habitable zone of its star, it does offer scientists one of the best opportunities for further study.

Compared to the stars orbited by exoplanets in the TRAPPIST-1 system, the star orbited by this exoplanet is relatively quiet.

This makes it easier to disentangle the effects caused by its atmosphere from the random noise of sunspots and solar flares.

Researchers say this represents a unique opportunity to study a planet that could potentially host life.