Todd Carney is clean and sober after years of alcohol-fuelled scandals prematurely ended his NRL career, but he has revealed he had to take a difficult path to get there.

The former NRL bad boy is now happily married to MAFS star Susie Bradley and the couple welcomed son Lion Daryl Carney in 2021.

Carney has been clean and sober for 14 months and is a proud father, but he had to hit rock bottom before he could get to this point.

His NRL career was plagued by controversy, including being charged with drink-driving and reckless driving, allegedly urinating on a man in a nightclub, hooliganism, being sacked by the Raiders and banned from his hometown of Goulburn. , New south Wales.

That led to him being dropped by the NRL and forced to play football with Far North Queensland side Atherton Roosters, before he was permanently banned from the NRL after a series of alcohol-related indiscretions, including the infamous drinker who saw him pretend. urinate in his own mouth.

Carney lives happily today with his wife Susie Bradley, daughter Baby and son Lion (pictured together)

Carney receives a hug from his mother Leanne after returning from being released by the NRL to win the Dally M Medal playing for the Sydney Roosters.

Her new life with Bradley was just what Carney needed, until she realized she was still on a very dark path.

“My life was going well, at least I thought so, until our relationship got really serious,” she said. Triple M Rush Hour with Gus, Jude and Dell.

‘My wife became pregnant with our son León and obviously her love for me was always going to be the same.

But she said, “Before you bring a child into this life, into this world, I don’t see you continuing to hurt yourself.”

And she was honest with me. She said: “You think you’re a rock star and you’re not. Yeah, I didn’t know you when you played rugby league and I don’t really care.”

“Then we separated for a while, and it was a difficult time, because [of] my values growing up.

“When people said, ‘Oh, when you want to have children, what do you want to be like?’ I said, ‘I want to be like my father.’

‘So I lost that value because I wasn’t with my son 100 percent of the time.

‘And in those moments, week after week, I was very good to him. When he had a week off, he lived like a rock star and I just didn’t care about myself or who he was.’

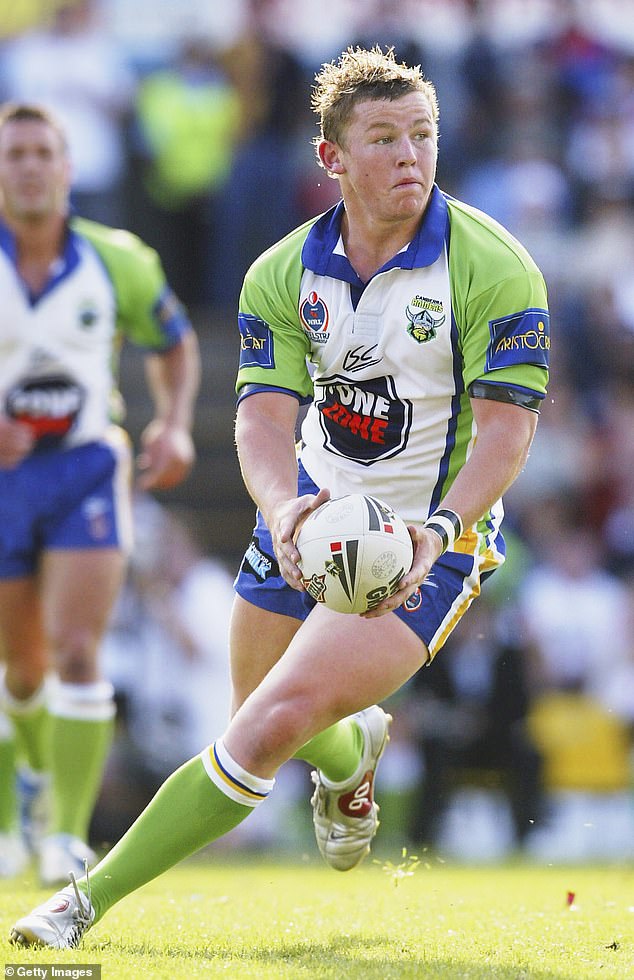

Carney was a precocious talent, but a series of alcohol-fueled incidents slowed him down.

This ‘bubbler’ image, in which Carney says he was only pretending to urinate in his own mouth, ultimately ended his NRL career.

Carney had gone to rehab and alcohol therapy many times before, but this time it was of his own free will and he was determined to make it work for the sake of his young family.

“This time I went to rehab to show that I was committed to doing it and I took responsibility for when I got out,” he said.

‘I know, I was that person for a long time.

‘I’ll stop drinking for a month, okay. Well, for that month all I did during the last 10 days of that month was [thinking] “I’m going to drink this Saturday, I’m ready to go.”

‘But now that I’ve given myself 14 months to live, people say that when you stop drinking alcohol, everything changes.

‘And I thought, I can’t change too much. But I am living proof that a lot has changed.

‘And that’s not through money or fame or glory or whatever. it’s through [the fact] that I am present in my life.

“I can wake up every morning fresh and I can look at myself in the mirror.”

Carney said that even when he was sober, he thought about drinking again, which led him down bad paths.

Carney is now 14 months into a clean, loving life with his family after facing his inner demons.

Carney then detailed how dark those days had become as he drank heavily during the time he was away from his son.

‘The morning before I decided to go to rehab, I physically couldn’t look at myself in the mirror. He was depressed and out.

And it’s not like I went out and drove drunk or did anything bad or anything like that. I physically couldn’t get up to take a shower and get ready for work.

‘That was telling me something. It was time, that was the moment.’