Nearly 50 years ago, archaeologists made an astonishing discovery when excavating the ancient city of Vergina in northern Greece.

They found three royal tombs containing remains of Alexander the Great’s family, dating back to the 4th century BC

At that time, they were considered the father, son, and elder half-brother of the great warrior.

But according to scientists, the father and half-brother have been caught in a case of mistaken identity that has lasted ever since.

In a new study, experts now reveal “conclusively” that the skeleton long identified as belonging to the half-brother is actually that of the father, and vice versa.

Researchers claim to have finally identified the remains of Alexander the Great’s father, Philip II of Macedonia. In the photo, bones of his left leg.

Part of the male distal femur of the knee in ‘Tomb I’, the tomb containing the father of Alexander the Great (Philip II)

Unfortunately, the resting place of Alexander the Great himself remains a mystery.

The new study was led by Antonios Bartsiokas, a professor of anthropology at the Democritus University of Thrace in Greece.

“The skeletons studied are among the most historically important in Europe,” say Professor Bartsiokas and his colleagues.

“We have focused our discussion on the scientific facts and historical evidence that impact the acceptance or rejection of the placement of King Philip II of Macedonia.”

Alexander III, commonly known as Alexander the Great, was king of Macedonia, a state in northern ancient Greece between 336 and 323 BC. C., and today he is considered one of the most successful military commanders in history.

His father, Philip II of Macedon, ruled the ancient kingdom before him, from 359 BC until his assassination in 336 BC.

While Alexander the Great’s resting place is unknown, researchers discovered three tombs at Vergina in 1977, named Tombs I, II, and III.

At the time, archaeologists proposed that they contained the remains of Alexander the Great’s father (Philip II), his son (Alexander IV) and his half-brother (Philip III of Macedonia).

But which tomb contained which person has been a “long-running debate,” according to the study.

Teeth from Tomb I: The one on the left is a “sturdy middle-aged adult male” and the one on the right is a young adult woman. Tomb I also contains the remains of a woman and a baby, who researchers believe are Cleopatra, Philip II’s wife, and her newborn son.

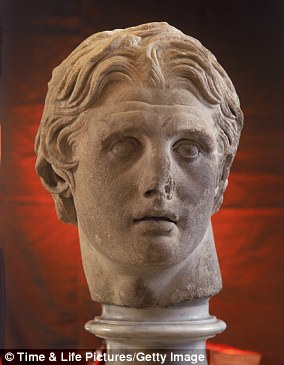

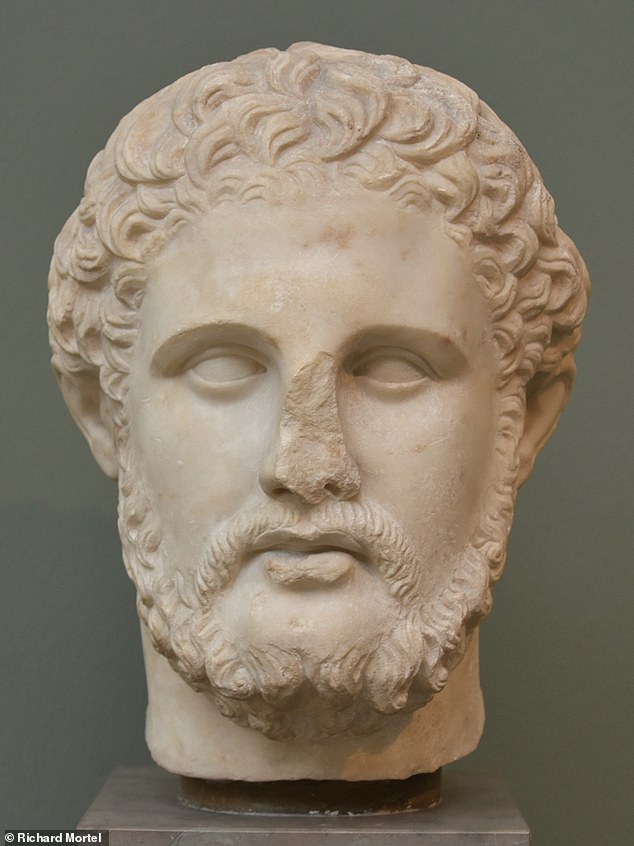

Bust of Philip II, king of Macedonia and father of Alexander the Great, on display in Copenhagen, Denmark

There has been a long debate over the identities of the occupants of the 4th century BC royal tombs at Vergina in northern Greece.

Most scholars agree that Tomb III belongs to Alexander IV, the teenage son of Alexander the Great, but the “gruelling debate” over the other two tombs “continues unabated.”

To settle the debate, researchers studied x-rays of the skeletons and consulted ancient writings about each figure, including their anatomical characteristics and possible physical problems.

They conclusively identified that Tomb I contained the father of Alexander the Great and that Tomb II contained Philip III of Macedonia, and not the other way around as previously assumed.

Tomb I contains the remains of a woman and a baby, who researchers believe are Cleopatra, the young wife of Philip II, and her newborn son.

Professor Bartsiokas agrees that this should have been a “gift”, but instead the academics were mistaken about its identity.

“They speculated that the female was Eurydice (Philip III’s wife), but offered no explanation for the newborn,” he told MailOnline.

“It is a well-established fact in ancient sources that Cleopatra was murdered along with her newborn son.”

Crucially, the documents reveal that Philip II of Macedonia suffered a severe traumatic injury to his left knee, which skeletal evidence corroborated.

Bone elements from Tomb I (until now mistakenly identified as belonging to Alexander the Great’s half-brother (Philip III of Macedonia)

Pictured is the unfused ilium (one of the three bony components of the hip bone) of the newborn from Tomb I.

“In the male skeleton from Tomb I, a knee fusion was found that coincides with historical evidence of King Philip II’s lameness,” the new study notes.

“These conclusions refute the traditional speculation that Tomb II belongs to Philip II.”

Meanwhile, no evidence of knee trauma was found on the male skeleton from Tomb II.

Furthermore, it was known that Philip II had an eye injury that blinded him, but there were no signs of this in the remains of Tomb II.

Unfortunately, there was no sign of the damaged eye in Tomb I either, as that part of the skull has not been preserved.

The forces of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) are depicted fighting those of the Indian Rajah Porus (active 327-315 BC) on the banks of the Hydaspes River (now the Jhelum River in Pakistan).

But Professor Bartsiokas and his colleagues believe that the available evidence is clear and that Alexander the Great’s father is found in Tomb I.

“We have provided compelling evidence from multiple sources that conclusively demonstrates that Philip II was buried in Tomb I,” they state.

“Our hypothesis of Philip II in Tomb I remains unchallenged in the peer-reviewed literature and we believe the available evidence is conclusive.”

The study has been published in Archaeological Science Magazine: Reports.