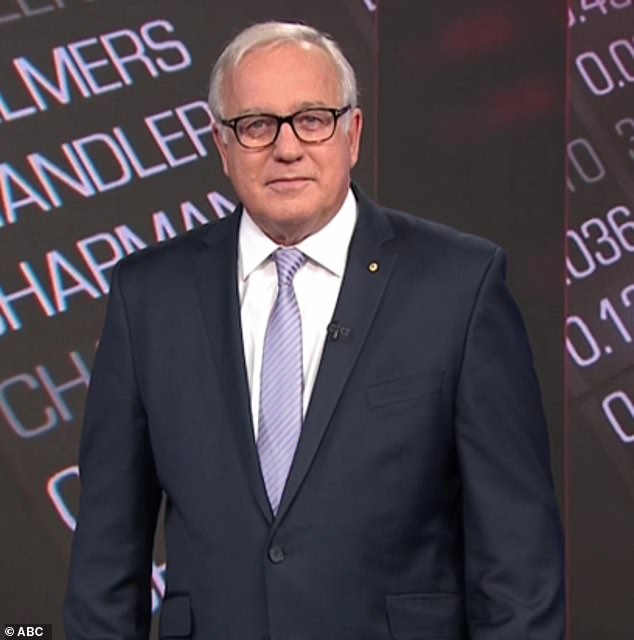

ABC finance expert Alan Kohler says Australian home borrowers are in a much worse position than their American counterparts, largely because of policies enacted during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Australian borrowers have been hit by 13 interest rate increases since May 2022 and with inflation remaining high, another rate hike remains a possibility.

Monthly Australian home loan repayments are 68 per cent higher than just over two years ago, following the most aggressive rate hikes in a generation.

Nearly all borrowers have a variable-rate loan (after ultra-low fixed rates expire), meaning each rate increase adds $100 to monthly payments on the average $600,000 mortgage.

In the United States, borrowers are typically offered 30-year fixed-rate loans thanks to the creation in 1938 of the Federal National Mortgage Association, better known as Fannie Mae.

The then United Australia Party prime minister Joseph Lyons refused to copy US President Franklin Roosevelt and by 2024 the big four banks will not offer fixed rates for more than five years.

Since then, the United States has created other government-sponsored mortgage financiers, Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae, meaning that American borrowers have certainty regarding their mortgage payments.

Kohler suggested that later Australian governments were reluctant to copy what American Democrats did during the Depression because of the banking lobby.

ABC financial commentator Alan Kohler argues that Australian home borrowers are far worse off than their American counterparts, largely as a result of policies enacted during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

“Why has no subsequent government, Labor or Coalition, created the Australian equivalent of Fannie, Freddie or Ginnie?” he asked in a Quarterly Essay article: The Great Divide, Australia’s Housing Crisis and How to Fix It.

-I don’t know, but I suspect it has something to do with the power of the banks, which don’t want to be stuck with thirty-year mortgages.

Negative gear

Instead, in 1936 the Lyon government legislated negative gearing as part of the Income Tax Assessment Act.

This allows investor landlords to claim rental losses against their taxable income.

Bob Hawke’s Labor government briefly eliminated negative gearing in 1985, but reinstated it in 1987 when the policy led to huge rent increases.

In 2019, the opposition Labour Party campaigned to abolish negative gearing for future investment property purchases, but lost its third consecutive election.

Anthony Albanese won the 2022 election after promising not to touch negative gearing and has since put an investment property up for sale in Dulwich Hill in Sydney’s inner west.

With negative leverage, investors can claim their losses on taxes and still get a 50 percent capital gains tax break when they sold at a profit.

Mr Kohler said existing negative leverage policies, now supported by both sides of the political aisle, had failed to address Australia’s rental crisis, with the national vacancy rate at just 1.4 per cent.

“This is happening despite the tax breaks that real estate investors get from negative gearing and the capital gains tax credit, which are supposed to boost the supply of rental housing. They obviously don’t,” he said.

A record 547,300 migrants moved to Australia in 2023, the most ever recorded in a calendar year.

Monthly Australian home loan repayments are 68 per cent higher than just over two years ago following the most aggressive rate hikes in a generation, but US mortgages are on 30-year fixed rates.

Immigration was more than five times the 100,000 annual levels of the late 1990s, and Kohler blamed John Howard’s coalition government for increasing immigration during the 2000s.

“The other consequence of increased immigration under the Howard government was a housing shortage, because there was no thought at all about where new arrivals could live,” he said.

Sydney’s median house price of $1.466 million is 12 times the median full-time salary of $98,218, even with a 20 per cent mortgage deposit.

Even the national median home price of $860,545 is out of reach for a typical-income person buying on their own who can only afford a $638,400 home.

That’s because banks can only lend 5.2 times what a person earns, and the Reserve Bank’s cash rate is at 4.35 per cent, its highest level in 12 years.

In May, variable-rate mortgages accounted for 98.3 percent of the $57.782 billion lent or refinanced to home borrowers, new data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics showed.