A hypervirulent, antibiotic-resistant bacterium that could spark the next pandemic has been detected in more than a dozen countries, including Britain.

At a briefing, representatives of the World Health Organization (WHO) warned of the potentially deadly impact of a little-known bacteria called Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The pathogen has been observed in the UK and the US, as well as in Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Canada, Cambodia, China, India, Iran, Japan, Oman, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Switzerland and Thailand.

Of these countries, 12 (including the UK) reported a specific strain of concern that has become a superbug resistant to all antibiotics used to treat it.

This comes as a separate report from WHO chiefs named Klebsiella pneumoniae as a “high-risk” pathogen that could trigger the next pandemic.

While Klebsiella pneumoniae has been around for years, experts are increasingly concerned about a “hypervirulent” strain, called hvKp. Pictured: A graphic representation of the Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteria

Although Klebsiella pneumoniae has been around for years, experts are increasingly concerned about the “hypervirulent” strain, called hvKp.

In this context, “hypervirulent” means an increased ability to make healthy people seriously ill, not just groups such as the elderly or immunocompromised individuals like cancer patients, who are traditionally more vulnerable to such infections.

To make matters worse, a particular substrain of hvKp, called hvKp ST23, has become resistant to “last-line” antibiotics called carbapenems, powerful cousins of the better-known penicillin.

These “last-line” drugs are the last remaining option for when a strain of bacteria like Klebsiella pneumoniae has become immune to other, more common drugs, a process called antimicrobial resistance.

This means that in many countries doctors can do nothing but try to keep a patient alive long enough for their body to fight off the infection on its own, without direct pharmaceutical help.

Worse still, these strains have the ability to “generate outbreaks” and infect more people, the WHO report says.

Klebsiella pneumoniae is considered one of the main causes of hospital-acquired infections.

Some studies estimate it is behind between one-fifth and one-third of pneumonias, a general term for inflammation of the lungs’ air sacs usually caused by a hospital-acquired infection such as Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The bacteria can also cause other types of serious health problems, including urinary tract infections, meningitis, a dangerous infection of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord, and even deadly sepsis.

Although more than a dozen countries told WHO they had identified cases of worrying strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae, only 43 of the 124 nations the global health body asked for data responded.

This means that the true extent of its global spread could be greater.

The WHO noted that a lack of testing for individual strains of the bacteria in some European countries may further contribute to an underestimation of prevalence.

“Since detection of hypervirulence is not part of routine microbiological diagnosis, hvKp may go undetected,” the report said.

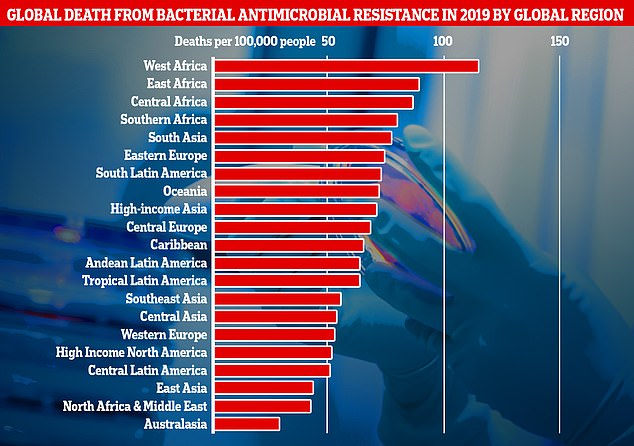

This chart shows the combined direct and associated deaths caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria by global region, as measured in the new research. Africa and South Asia recorded the highest number of deaths per 100,000 people, however, Western European countries, such as the UK, recorded significantly high numbers of deaths.

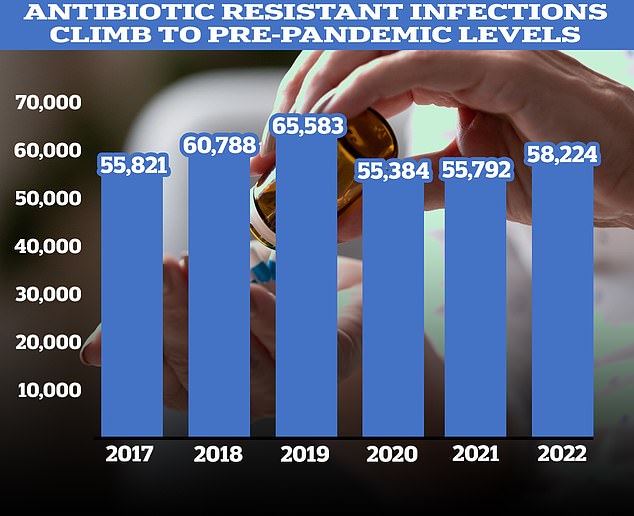

Figures show a marked recent rise in the number of antibiotic prescriptions after years of decline. According to the UKHSA, 58,224 people in England had an antibiotic-resistant infection in 2022, up 4% from 2021.

The WHO added: “Many physicians in countries in the European region have not yet experienced the clinical presentation and extended spectrum of hvKp disease.”

The WHO concluded its report by saying that based on current evidence, the risk posed by HVKP to global health is “moderate.”

It recommended that nations increase their laboratory diagnostic capacity to better track HVKP cases, as well as improve the ability of those laboratories to analyze the genetic makeup of those strains for genes that increase their ability to infect people and evade drugs.

UK health officials have also noted a worrying decline in the effectiveness of drugs designed to combat Klebsiella pneumoniae in general.

A report from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) published late last year detailed that Klebsiella pneumoniae was now 17.4% resistant to first-line antibiotics. This was up from 13.5% in 2018.

Cases of Klebsiella pneumoniae have also been increasing in England.

UKHSA data recorded a total of 11,823 cases in 2022/23, an increase of just over a fifth compared with the 9,806 cases recorded five years earlier.

This comes as a separate WHO report names Klebsiella pneumoniae as one of more than 30 pathogens most likely to cause the next pandemic.

The growing threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae is just one example of a pressing global problem called antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Colloquially dubbed “superbugs”, experts have warned that the rise of pathogens that have developed resistance to drugs commonly used to help patients fight back will make the Covid pandemic seem “minor” by comparison.

Professor Dame Sally Davies, England’s former chief medical officer, has warned that antimicrobial resistance could kill more people worldwide than climate change if the threat is not taken seriously.

It is estimated that AMR already kills around 1.2 million people each year worldwide, more than HIV or malaria, and contributes to the deaths of another 5 million.

In Britain specifically, AMR is thought to kill nearly 8,000 Britons a year, with many more suffering long-term health consequences from the infection.

The WHO itself predicts that the global number of direct deaths from antimicrobial resistance will rise to 10 million per year by 2050.

Globally, excessive and inappropriate use of drugs such as antibiotics is one of the factors driving the development of AMR.

This includes people taking drugs like antibiotics when they don’t need them, but also giving them to farmed animals on an industrial scale in an attempt to preemptively stop infections and increase profits.

This agricultural use allows huge quantities to leak into the environment, where pathogens can develop resistance.

Experts have warned that if AMR becomes increasingly common, it could lead to surgeries such as Caesarean sections and treatments that weaken the immune system, such as chemotherapy and organ transplants, becoming much riskier, with potentially fatal consequences.

One of the few ways that AMR can potentially be combated is the development of new classes of antibiotics to which pathogens have not yet adapted.

However, there have been no similar advances since the 1980s.

One barrier to developing new drugs is cost. Industry estimates suggest the cost of developing a new antibiotic is £1 billion, well below the estimated revenue from selling one of them, which is about £35 million a year.

Revenues are expected to be so low because health chiefs will only use these drugs as a last resort, in an attempt to stop or slow the development of new pathogen resistance and bring AMR back to square one.

Different funding models have been suggested to address this problem, such as a subscription model that pays companies for access to superbug-fighting drugs on an annual basis, regardless of usage, but these models have yet to bear fruit.