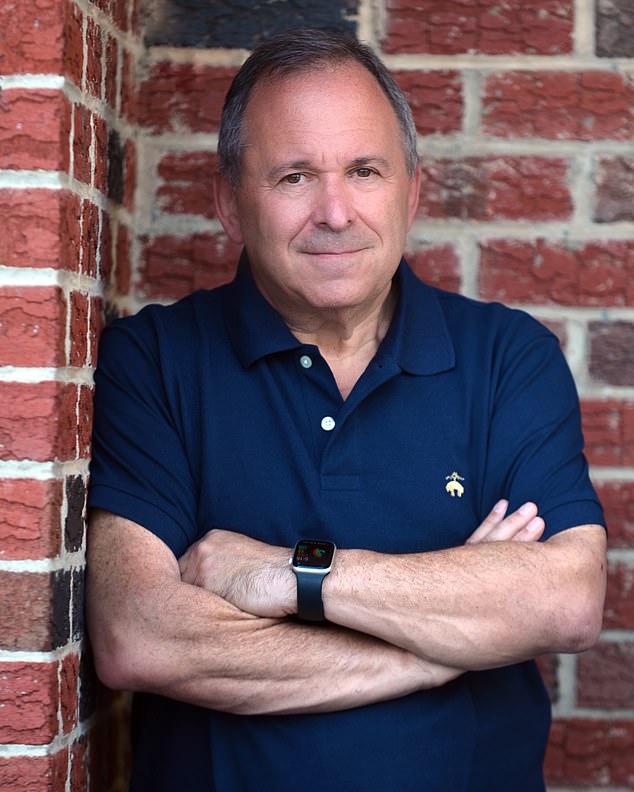

David Rimmer was flying over the jungle from Manaus in Brazil on a business trip in 2006 when the private jet he was traveling in collided with a Boeing 737 800 in a collision unlike any before in the history of aviation.

Rimmer, 64, told DailyMail.com that his plane, with seven people on board, was cruising at 37,000 feet when he heard what he describes as a “very sudden jolt.”

“There was no warning,” he said, “we really had no idea what it was, but it was more serious than a typical blow in the clouds.” But we couldn’t see anything.’

The planes have technology designed to warn of impending collisions, but that day it didn’t work: Rimmer and the two pilots of the plane only knew that something serious had happened when they saw that the ‘winglet’ on the nose of their plane had been damaged.

The plane’s cockpit voice recorder was found in the jungle (Brazilian Air Force)

Brazilian Air Force inspects the wreckage of the Boeing 737 800 (Brazilian Air Force)

Rimmer has been married for 34 years. He and his wife have two daughters who were 10 and 12 years old at the time of the incident.

“It was hard not to keep thinking about how bad it could end and how badly it would affect my family, but I tried really hard not to focus on the possibility,” she said.

“It would have made it scarier.”

Rimmer recalled that the rear of the cabin was “pretty quiet and reserved.”

“We had no means of communicating with land, there were no phones and WiFi was not activated,” he explained.

‘One of the passengers, Joe Sharkey of the New York Times, wrote a farewell note to his wife but didn’t tell us until we landed safely.

“I wish I had the presence of mind to write to my wife and daughters, but I didn’t.”

The 86-foot Embraer Legacy 600 executive jet was flying from where it was manufactured to the U.S., Rimmer explained.

Rimmer said: ‘We looked at the left side of the plane and the wing, instead of this smooth piece of metal, it was this jagged edge. He had clearly been cut off by something. But we really had no idea what it was.

The approach speed (in fact, the combined speeds) of the two planes was 1,000 miles per hour, Rimmer learned after the 2006 collision, which meant there was no way they could have seen anything.

Rimmer said: “Our crew took control of the aircraft and was severely compromised.”

One of Rimmer’s colleagues looked back and saw that an “almost surgical” piece of his tail had also been cut off.

He said: ‘There was nothing I could do but hold on and keep my wits about me. It would have been very easy to fall into this overwhelming fear, but it would have been of no use.

‘It would have just made the next period of time that much scarier. It was quite solemn in the cabin.

‘It was very calm. We just knew we were in serious trouble and hoped for the best. And about 35 minutes later, we landed at this remote military base in the Amazon.”

It was a calm, peaceful day when David Rimmer’s business jet collided head-on with a Boeing 737 800.

Only when the crew was sitting at the table eating pizza did the only Portuguese speaker among the crew make a horrifying discovery.

Rimmer said, “He came back to our table and said, ‘Guys, I have terrible news to share with you.’ Along our flight route there is a missing plane and they don’t know what happened to it, but it’s too much of a coincidence.

The crew went from a sense of relief to terrible sadness, Rimmer said.

They also realized how small their chances of surviving such a collision had been.

Rimmer said: “The chances of anyone surviving that type of accident are minimal.” I don’t think it’s happened before.

‘If the plane was a few centimeters lower, it would have come off our wing. If it was even a couple of centimeters closer to us, it would have taken our tails off and neither of us would be able to survive. It is simply impossible to imagine how close the decision was.”

The collision between the Boeing and Rimmer’s plane severed the wing of the larger plane.

An Embraer Legacy 600 similar to the one in the accident (file image)

The Boeing 737 crashed in the jungle, killing all 154 passengers and crew.

The investigation into the crash became highly politicized in Brazil, and at points blame was placed on the pilots of the smaller planes.

But Rimmer said that despite the different conclusions of the Brazilian investigation and the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), he believes the failure lies “fundamentally” in the failure of air traffic control to keep separate to the two planes.

He said: ‘Our pilots have no vision of the sky. Only air traffic controllers know this.

Rimmer has since campaigned to improve aviation safety and still works in aviation as chief executive of AB Aviation.

He said the accident fundamentally changed his outlook on life.

He said: ‘The initial challenge was figuring out why us? Why are we saved? 154 people were not. There is no answer to that question.

‘The next question is, what do I do with this gift? It is not a total celebration, because our survival was linked to such a tragedy. There is gratitude, but you never want to lose sight of the loss.’

It was a calm, peaceful day when David Rimmer’s business jet collided head-on with a Boeing 737 800.

Rimmer said he still thinks about the accident daily and that every day now feels like a “gift,” and he said he now tries to be more charitable, more generous, focus on family and be a better father.

He donates to non-aviation causes and also campaigns to improve safety.

He says: I feel it is my duty to try to raise awareness of safety issues in the aviation community. I use the lessons learned from being a part of such a serious accident in the hopes that it will help save other lives.

He says: “All of us on the plane celebrated two birthdays.” One is our chronological birthday and the other is the day we were saved.