Native title, a legal recognition of Aboriginal rights over an area, will cover 60 per cent of Australia’s landmass over the next 15 years, as Labor announces an inquiry into the “inequality and injustice” of the legislation.

Native title holders can get compensation for things the government has done to prevent them from exercising their rights, such as building a bridge or road.

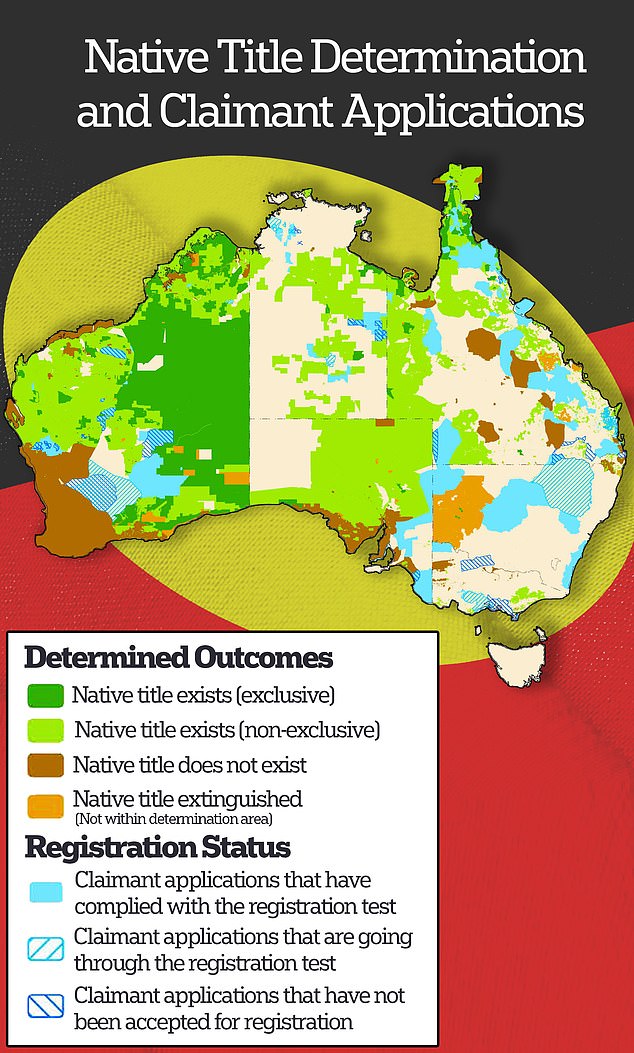

A map prepared by the National Native Title Tribunal shows that almost 50 per cent of Australia currently has native title. The sections are divided into dark and light green to distinguish between “exclusive” and “non-exclusive” zones.

A further 12 per cent of the land is being assessed for native title, and these areas are coded with blue patches or stripes.

That means native title will cover 60 per cent of Australia’s landmass in the next 15 years.

However, less than nine percent of indigenous people are members of a native title corporation and only half of these companies make money due to strict laws governing how land can be used, according to the Australian Financial Review.

On Tuesday, Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus announced a $550,000 investigation into the Native Title Act, with the Australian Law Reform Commission tasked with identifying any “inequities, injustices or weaknesses” in the legislation.

A stunning map has revealed native title stretches across half of Australia and more claims are currently being assessed in other parts of the country.

It is important to note that native title can only be claimed for Crown land and is not applicable to private property.

Where a native title determination specifies “exclusive” rights, it means that the Indigenous group has exclusive ownership and control over the area in question, excluding all others, including government authorities and non-Indigenous individuals or entities.

Non-exclusive native title in Australia gives indigenous groups shared rights and interests in land without exclusive control.

It may give native title holders the right to local cultural practices, such as the right to live in the area, hunt, fish, gather food or teach laws and customs in the country.

However, it does not give them rights to the minerals: those rights are reserved by the Crown.

Less than nine per cent of Indigenous people are members of a native title corporation and only half of these companies make money due to strict laws governing how land can be used.

Shadow Indigenous Affairs Minister Jacinta Nampijinpa Price (pictured) has called for reform of the Native Title Act for “land-rich and very poor” Indigenous communities.

And since their rights are tied to traditional laws and customs, they couldn’t build a casino like America’s First Nations people did.

To claim native title, it is necessary to demonstrate a long-standing connection to the land through tribal laws and customs that predate European settlement.

Claims are registered with the National Native Title Tribunal and are resolved in the courts, including the Federal or High Court and state Supreme Courts.

After the inquiry was announced, Shadow Indigenous Affairs Minister Jacinta Nampijinpa Price called for reform of the Native Title Act for “land-rich and very poor” Indigenous communities.

‘In native title terms it was well intentioned and it’s very nice to be able to have access to your land as a traditional owner for fishing and hunting. It was very limited in terms of what else indigenous Australians could do,” Senator Price told Sky News.

‘Ideas such as economic development, economic independence, the opportunity to generate wealth from one’s own land. “It was a very limited scope to be able to do that to begin with.”

He added: “I’ve always said that traditional owners, you know, are land rich, very poor and need to be able to be job creators in their own right, in the country, rather than continually relying on welfare.” and about the government.

“In practice, we don’t have access to the sea in terms of how we can and can’t use our land.”

However, not everyone agrees.

Last year, Senator Pauline Hanson pushed for a royal commission into granting native title, but her proposal was roundly rejected, with only five other senators supporting the motion.

He argued that two-thirds of Australia could potentially be controlled by less than two per cent of the population under native title legislation.

‘Under current law, there is an infinite period of time during which claims can be brought, he explained.

“That means 100 years from now groups could still be filing lawsuits.”

Senator Pauline Hanson (pictured) has previously argued that two-thirds of Australia could potentially be controlled by less than two per cent of the population under native title legislation.

He said that by withdrawing federal funding from respondents but continuing to provide money to native title claimants, the Albanian government had created a very unequal playing field.

“There are many thousands of these native title and other land claims across Australia,” he told Daily Mail Australia last September.

‘I suspect many people living in those yet-to-be-determined areas don’t even realize they are at risk of their communities being converted to native title.

‘Native title claimants get all their legal costs fully funded by the Australian Government, but not by the organizations that must respond to these claims, because Labor has abolished the Native Title Claimants Funding Scheme.

“So if your community is under a native title claim, the government will fund it from your taxes.”

He said that because native title claimants must meet a stricter eligibility standard than those claiming indigenous heritage, two-thirds of Australia could potentially be controlled by less than two per cent of the population.

‘Native title holders directly receive income in the form of mining royalties and other uses of the land under their control.

‘These are just more examples – along with Voice to Parliament – of the Albanian Labor government treating Australians unequally based on race.

‘Since the beginning of my political career, I have denounced this unequal treatment based on race. “I will always fight for equality for all Australians.”

Meanwhile, a decade-long dispute over two native title claims is coming to an end, with First Nations traditional owners seeking to take possession of 7,800 square kilometers of Australia.

The Barada Kabalbara Yetimalara people are bidding for native title for two areas in central Queensland and the Federal Court of Australia will deliver its verdict soon.

Local media reported that they had won the legal battle, but the Federal Court confirmed that a final decision has not yet been made.

On Tuesday, Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus announced a $550,000 investigation into the Native Title Act, with the Australian Law Reform Commission tasked with identifying any “inequities, injustices or weaknesses” in the legislation. An Aboriginal protester at a demonstration in Perth.

One parcel of land covers more than 7,512 square kilometers between Sarina and Rockhampton, while the second covers 294 square kilometers of land and water north of Rockhampton.

Indigenous property applications were first submitted in July 2013.

They are the first to affect the Isaac region, west of Mackay, in several years.

Native title differs from land rights, which only exist under the laws of New South Wales and the Northern Territory.

Land rights mean that a local land council can claim absolute ownership of any unused or misused Crown land as compensation for historical dispossession.

These claims are assessed by government departments.

Both land rights and native title can coexist on land and can even lead to conflict between traditional owners.

Traditional owners have gained freehold land rights to 50 per cent of the Northern Territory, including 85 per cent of its coastline.

There have been more than 3,000 successful land rights claims in New South Wales, but almost 40,000 remain to be assessed.