A Dutch woman who was granted permission to end her life by euthanasia despite being a physically healthy 29-year-old has dismissed the public backlash and declared she will die within weeks.

Zoraya ter Beek, who suffers from depression and borderline personality disorder, was approved for assisted dying last week and hopes to soon be “released” from her torment.

But this week he lashed out at critics, calling their protest “insulting.”

“People think that when you have a mental illness you can’t think clearly, which is an insult,” he said. the Guardian.

‘I understand the fears that some disabled people have about assisted dying… bBut in the Netherlands we have had this law for more than 20 years. “There are very strict rules and it’s really safe.”

Euthanasia has been legal in the Netherlands since 2002 for those experiencing “unbearable suffering with no prospect of improvement.”

Zoraya ter Beek, (pictured), who lives in a small town in the Netherlands, suffers from depression, autism and borderline personality disorder. She has decided to end her life by euthanasia after a psychiatrist told her “there is nothing more we can do for you” and that she will “never get better.”

It is understood that a doctor will give you a sedative before giving you a medication that will stop your heart. Ter Beek appears in the photo in 2017 with his do not resuscitate plaque

Ter Beek decided he wanted to die after a psychiatrist told him “there is nothing more we can do for you” and that “you will never get better.” The free press reported.

It is understood that a doctor will give you a sedative before giving you a medication that will stop your heart.

She previously said she would be euthanized on the couch at home with her boyfriend by her side.

Ter Beek said her crippling depression and anxiety caused her to self-harm and become suicidal for years, claiming that no mental health treatment, which to date has included talking therapies, various medications and even electroconvulsive therapy, has worked to reduce her distress. . .

When he was just 22 years old, ter Beek opted to get a do-not-resuscitate badge, something older people often wear.

He had thought about suicide on many occasions, but resisted after seeing the devastating impact the violent suicide of a schoolmate had on his family.

Instead, she decided to begin the process of getting permission for assisted dying three and a half years ago after doctors reportedly said there was nothing more they could do to help improve her mental health.

The 29-year-old told The Free Press last month that she has always been “very clear that if it doesn’t get better, I can’t do this anymore.”

Her boyfriend will spread her ashes in “a nice place in the woods” they have chosen together, she said.

“I don’t see it as my soul leaving, but rather as myself being released from life,” she said of her expected death, admitting: “I’m a little afraid of dying, because it’s the ultimate in the unknown.” .

‘We don’t really know what’s next, or is there nothing? That’s the scary part.’

Ter Beek has carefully planned his “release”, telling the newspaper that he will “sit on the sofa in the living room” and there will be “no music”.

He explained that “the doctor really takes his time” and will first try to “calm the nerves and create a gentle atmosphere.”

Then, according to ter Beek, the doctor will ask her if she is ready before “taking my place on the couch.”

The doctor will ask “one more time” if ter Beek wants to carry out his euthanasia, before starting the procedure and wishes him “a good trip.”

Ter Beek added: “Or, in my case, a good nap, because I hate it when people say, ‘Have a good trip.'” I do not go anywhere.’

After ter Beek’s death, a euthanasia review committee will evaluate his case to ensure the doctor met all “criteria of due care” and, if so, the Dutch government will declare his life legally ended.

Ter Beek has always been “very clear that if he doesn’t improve, I can’t continue with this.” She has decided not to have a funeral and she will be cremated.

When he was just 22 years old, ter Beek opted to get a do-not-resuscitate badge, something older people often wear.

The Netherlands is one of only three EU countries where the practice of assisted dying is legal, and human rights groups argue that it gives people battling terminal or disabling illnesses the right to end their suffering. human form.

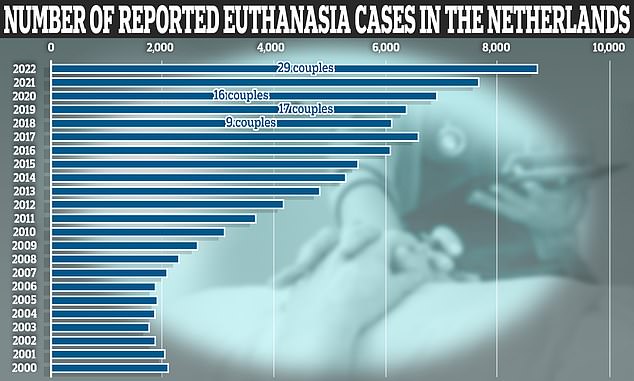

The data revealed that 8,720 people in the Netherlands ended their lives through euthanasia in 2022, an increase of 14 percent from the previous year.

The figure represents 5.1 percent of all deaths in the country, but the true figure could be much higher as research suggests that around 20 percent of euthanasia deaths go unreported, according to Dutch media.

No scientific research has been carried out to establish a reason for the dramatic increase in people choosing euthanasia, according to the Netherlands’ Regional Monitoring Committees (RTE) that track deaths.

Under Dutch law, to be granted the right to euthanasia, a patient must obtain the consent of two independent doctors, who must agree that their case meets detailed criteria.

The patient in question must also be considered “mentally competent” to make the decision to perform euthanasia, something that poses a problem for patients suffering from dementia who request euthanasia but are not said to be of sound mind.

However, the Dutch government is working to make the practice of euthanasia accessible to a wider range of people following campaigns by various human rights groups.

The latest figures from the Regional Monitoring Committees (RTE) of the Netherlands show that 8,720 people ended their lives by euthanasia in 2022, an increase of 14 percent on the previous year.

In April last year, it was announced that parents in the Netherlands can euthanize their terminally ill children aged 12 and over, with plans to introduce laws to expand euthanasia regulations for terminally ill children aged one and 12 years.

Such an expansion would apply to approximately five to 10 children a year, who suffer unbearably from their illness, have no hope of getting better and for whom palliative care cannot provide relief, the government said.

However, some experts believe that the gradual relaxation of the country’s euthanasia law could lead to a “slippery slope” that could cause physically and mentally healthy people who “discover that their life no longer has content” choosing to die prematurely.

Stef Groenewoud, a health ethicist at Kampen Theological University, told The Free Press that she now sees doctors and psychiatrists treating euthanasia as an “acceptable option” rather than “the last resort,” as it was before.

“I see this phenomenon especially in people with psychiatric illnesses, and especially in young people with psychiatric disorders, where the healthcare professional seems to abandon them more easily than before,” Groenewoud said.

Theo Boer, a professor of healthcare ethics at the Protestant Theological University of Groningen, echoed Groenewoud’s claim, saying that while serving on the review committee for nine years he saw how the Dutch practice of euthanasia “evolved from death as a last resort to death as a default option.” ‘.

Scottish lawmakers are expected to debate an assisted dying bill next fall that would allow adults with an incurable illness to request a lethal dose of medication from their GP. Doctors who have a ‘conscientious objection’ will be able to opt out of the safeguards proposed in the bill (file photo)

Meanwhile, Scottish lawmakers are expected to debate an assisted dying bill next fall.

Under the Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Patients (Scotland) Bill, tTerminally ill Scots as young as 16 will be able to ask doctors for help to end their lives.

The legislation proposes that adults with an incurable illness can request a lethal dose of medication from their GP. Doctors who have a “conscientious objection” will be able to opt out under the safeguards proposed in the bill.

Supporters say the law will ensure people have the option of “safe and compassionate assisted dying.” But critics have condemned the legislation as “dangerous” and warned it will “normalise” suicide.

MPs are expected to be able to vote freely on the issue, with the bill likely to face its first test at Holyrood later this year before a final vote is held sometime in 2025.

- For confidential assistance, call Samaritans on 116123 or visit a local Samaritans branch, see www.samaritans.org for details