Scientists have discovered a new species in Utah’s Great Salt Lake that could change what we know about its ecosystem.

An investigation into the 950-square-mile body of water began when a University of Utah researcher saw a sign that said only brine shrimp and flies can survive the extreme levels of salt.

Believing that the signaling was false, because other creatures can thrive in similar ecosystems, the expert and his team began examining the sediment deposits and found a previously unknown species: thousands of small worms called nematodes.

Nematodes once populated the Great Salt Lake, but were thought to have disappeared in 1985 when the lake bed shrank and exposed them to the air.

The researcher’s findings not only prove that the lake’s ecosystem is more alive than previously thought, but because the lake’s water has reached record levels, it shows the importance of healthy lake elevation.

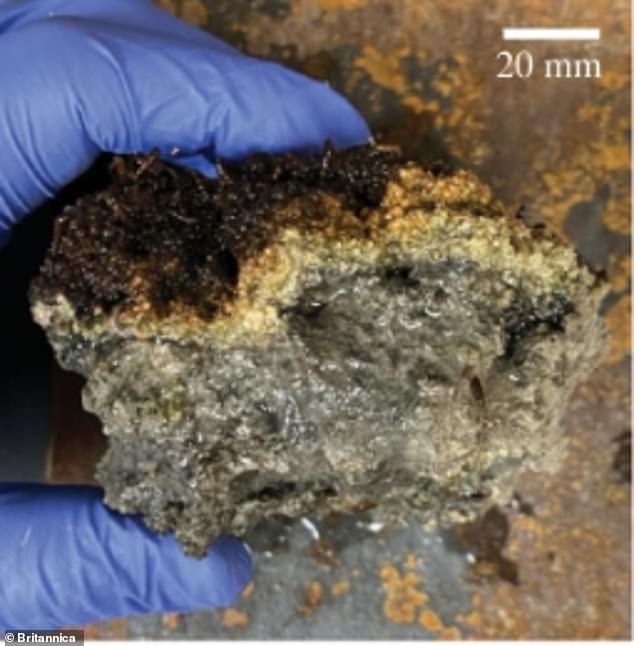

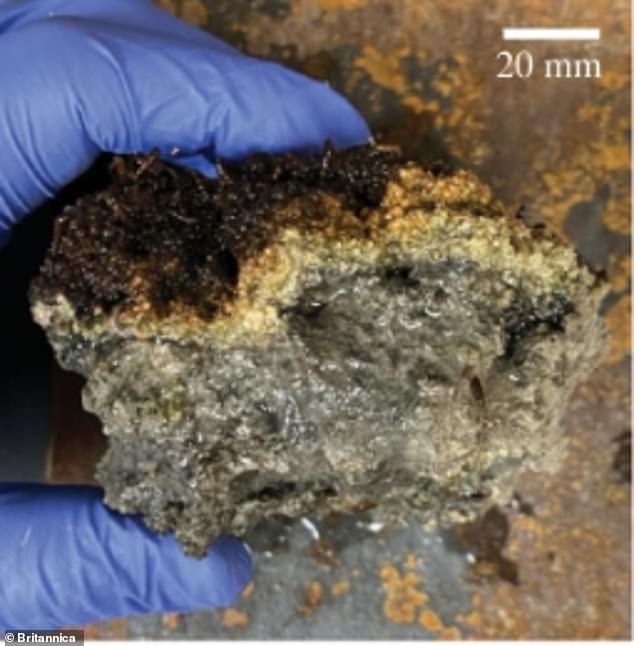

Microbialites form when organisms such as algae and bacteria form a mat in rock.

Researchers at the University of Utah found tiny worms living on a reef-like rock in the Great Salt Lake.

Michael Werner, a biology professor and nematode expert, saw the sign during a hike in 2020 and immediately questioned it.

«Nematodes are an almost ubiquitous group of organisms that are found in all types of environments. Some of those environments are very extreme,’ he told local outlet KSL.com.’

Then I thought, ‘Maybe no one has looked at it closely?’

Werner took his speculations to his colleagues who joined him on the mission to see if nematodes really lived in extreme levels of salt, which are two to nine times saltier than three percent of the ocean.

Together with his postdoctoral student, Julie Jung, Werner crossed the lake, first by boat and then by bicycle when water levels fell to a record low in 2022.

Werner told The Tribune that Jung had suggested there might be more nematodes living inside microbiocytes, sedimentary deposits made of carbonate mud, before taking a hammer to the reef-like rock.

“Julie had taken a hammer and was pulverizing a microbialite,” he said.

“He found hundreds, and in some cases thousands, of worms. “That really opened up this whole project for us.”

Microbialites form when organisms like algae and bacteria form a mat on the rock that gives it that slippery coating when you walk on it.

Nematodes are small worms that can live in extreme and harsh conditions.

It attracts minerals from the water that build on the existing rock structure and are often found along faults and cracks in the outer areas of the Great Salt Lake.

These are compared to coral reefs found in the ocean because they host lake life forms, such as brine flies, which attach to microbes as they grow into adults before floating to the surface.

In turn, its appearance on the water serves as a food source for migratory waterfowl and shorebirds.

Werner and his team wanted to understand if the microbes helped the nematodes survive or if it was the other way around.

They conducted a test by feeding non-lake nematodes the microbes’ bacteria and exposed them to salty lake water along with a control group of non-lake nematode worms that were only fed their usual fungal diet.

The control group of worms died within 24 hours, while the nematodes that fed on the bacteria were still alive.

“It opened up this whole exciting area of ecology of what worms do in the lake,” Werner told the outlet.

«Perhaps nematodes also contribute to the formation of microbes. … They could be transporting useful bacteria to other parts of the microbiocyte.’

More research still needs to be done, but Werner is hopeful that this can not only help understand how the Great Salt Lake ecosystem works, but also shed light on how organisms survive on other planets, such as Mars, that have extreme weather conditions.

“I think people look at the lake and hear about it as kind of a stinky, lifeless place in our backyard, but it’s so much more than that,” Jung said. KSL.com.

“The more you look, the more you find.”