At a time when mental health is talked about more than ever, there is a group of experts who fear that we have gone too far.

Schools across the country are implementing mental health awareness campaigns and promoting mindfulness and meditation techniques in classrooms.

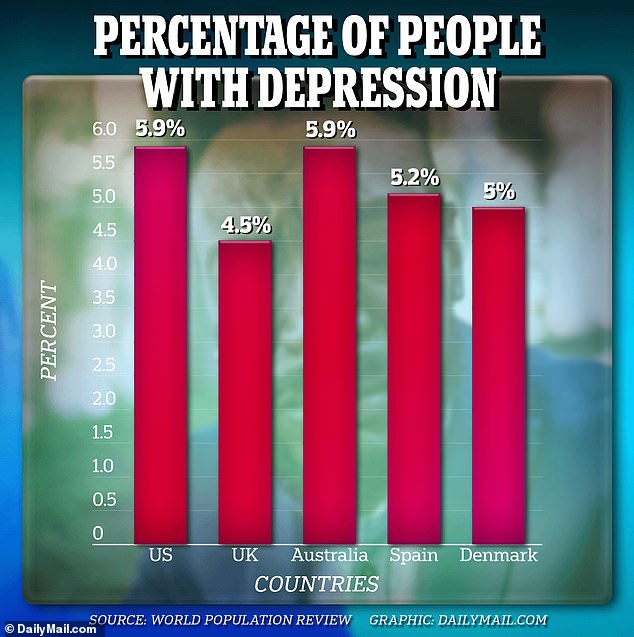

However, there is some evidence that increased awareness and attention to mental health is having the opposite effect and is not helping children at all, but rather making anxiety and depression worse.

My Resilience in Adolescence, or MYRIADThe trial followed thousands of students practicing mindfulness exercises in schools, and the results showed that not only did the exercises fail to improve adolescents’ mental health, but those most at risk of mental health problems did worse afterward. of training.

The researchers attributed the results to multiple reasons, but said one explanation was that mindfulness brought “awareness of disturbing thoughts.”

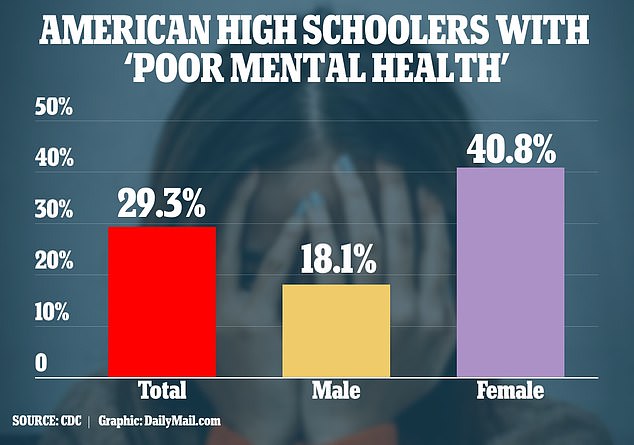

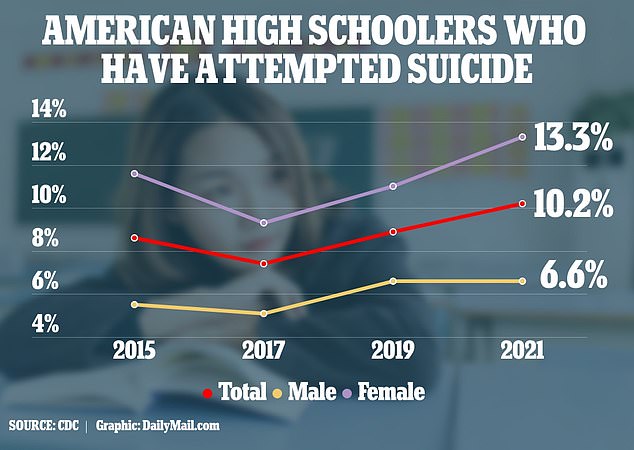

The CDC found that one in ten U.S. high school students attempted suicide in 2021, up from 8.9 percent the year before. Women were hardest hit: 13.3 percent attempted suicide that year.

However, the study found that mindfulness practices had a positive effect on teachers at the school.

The researchers noted that there are many things that can affect a younger, still-developing person’s mental health, including their environment, socioeconomic status, family dynamics and parenting, genetics and schooling, such as homework, exams and social aspects.

In a similar Australian studyThe researchers found that students who had taken a course of cognitive behavioral therapy reported higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms six and 12 months later.

In both studies, researchers were concerned about something called co-rumination, which is when a person repeatedly discusses problems with others instead of looking for solutions.

This excessive insistence on problems seemed to be greater among women.

Dr Jack Andrews, who led the Australian study and is a member of the Wellcome Trust, a UK-based health research organisation, said The New York Times: “It could be that they get together and make things a little worse for each other.”

He added that he thinks schools should proceed cautiously with mental health curriculum until “we know a little more about the evidence base.” Doing nothing is better than doing something.’

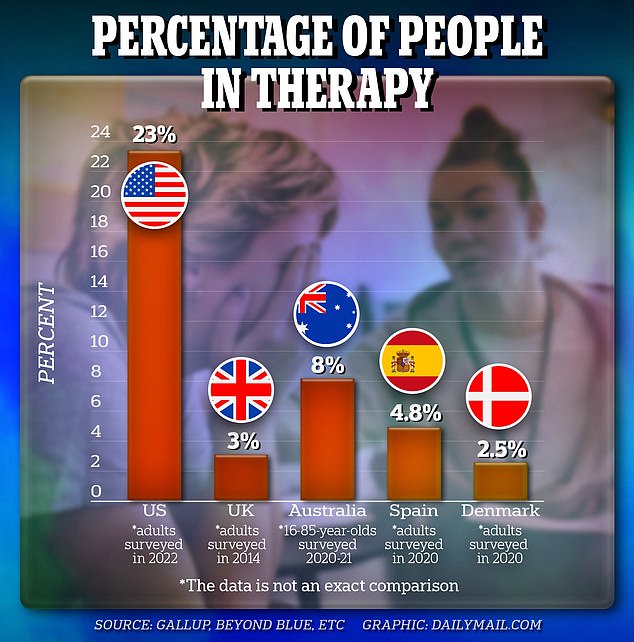

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, 13.8 percent of children and adolescents ages five to 17 received counseling or therapy in 2022.

Colorado-based psychologist Dr. Shawn Smith previously told DailyMail.com that the therapy may be harming American youth by “encouraging kids to spend, frankly, too much time navel-gazing and not engage in the world.” nor develop meaningful relationships and activities. .

‘To any extent, therapy contributes to this. It’s a problem.’

Dr. Smith added: “The way we know people are depressed is that they turn inward… and usually you will see relentless scrutiny of yourself, your thoughts, your feelings and your presentation.” “.

Excessive therapy can contribute to this: ‘If we have children who are just mindlessly examining themselves, then we are setting them up to turn inward and collapse inside, collapse in on themselves and become depressed. ‘

Despite the misgivings of some, Dr. Jessica Schleider, an associate professor of medical social sciences at Northwestern University, argued that addressing mental health issues in young people should be a priority for public health agendas.

She told the Times: ‘The urgency of the mental health crisis is very clear.

“In the partnerships I have, the emphasis is on kids who are really struggling right now and have nothing (we have to help them with) other than a potential risk to a subset of kids who aren’t really struggling.”

He warned against interpreting the study results as a reason to “forget everything.” Instead, he said experts should ask themselves: “What about this intervention was not helpful?”

Dr. Schleider said experts should move from the “one-size-fits-all, assembly-style approach” to more individualized and targeted interventions, which research shows can be effective in helping improve mental health.