Doctors in Canada are expressing serious concerns about a growing trend of euthanizing people who are not terminally ill.

Newly discovered communications reveal that many doctors charged with carrying out assisted dying have found the relaxation of criteria “morally distressing.”

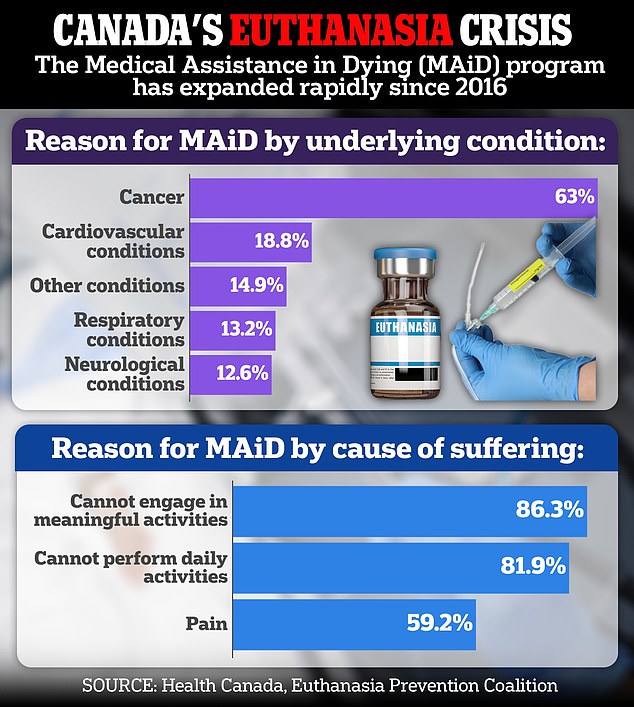

In 2021, Canada expanded its medical death law to include people with incurable, but not terminal, illnesses, leading to a 30 percent increase in assisted deaths in 2022.

An Ontario doctor wrote in his patient’s report that while the man had severe lung disease, what led to euthanasia was “primarily because he is homeless, in debt, and cannot tolerate the idea of (home care). long term) of any kind. ‘

In another case, a doctor expressed conflict about euthanizing a patient simply because she was obese and depressed.

Meanwhile, an old woman wanted to die because she was fighting the pain of losing her husband.

An associated press investigation that involved obtaining internal data from the Ontario provincial government revealed dozens of online posts by doctors in public forums.

The doctors provided the AP with messages shared on private forums for assisted dying specialists on condition of anonymity.

The messages came from doctors who performed euthanasia and evaluated people who requested it.

Many said they were uncomfortable with ending the lives of people who were not medically vulnerable.

Others felt conflicted about providing euthanasia to people who were not terminally ill, but to those who were grieving or obese.

An Ontario doctor who spoke to the AP revealed that his patient had severe obesity and depression, and said he felt like a “useless body taking up space.”

He had withdrawn from activities and social life and said he had ‘no purpose’, according to the doctor who reviewed his case.

While he was not actively dying, doctors said euthanasia was justified because obesity is “a medical condition that is really serious and irremediable.”

Meanwhile, a woman in her 80s requested assisted death after losing her husband, brother and cat within a six-week period, according to an AP report.

On top of that, he was on dialysis, a grueling procedure done every three weeks in which someone is hooked up to a blood filtration machine for about four hours at a time.

But the official who reviewed his request said it had nothing to do with a medical condition, but rather his pain.

Because he had lost his support system, the doctors said his suffering was permanent and therefore approved his request.

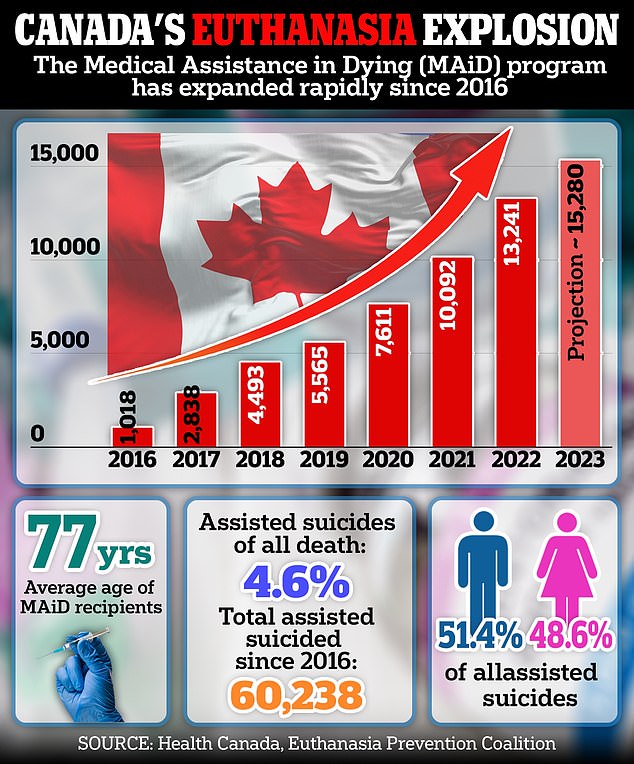

Canada is on track to break euthanasia records once again with 15,280 deaths by doctor-assisted suicide in 2023, a 15 per cent increase on the previous year, a campaign group warns.

Alex Schadenberg, director of the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition, says more and more people are being approved for euthanasia even when they suffer from nothing more than “frailty” and other seemingly benign conditions.

Approximately 60,238 people have died from MAiD since the program was launched in 2016.

As part of its investigation, the AP obtained a copy of a classified report written by Ontario’s Ministry of Attorney General that acknowledged past mistakes it had made in implementing its expanded MAiD law.

Rosina Kamis, 41, suffered from chronic leukemia, but a letter in her will states that the mental anguish she suffered was the reason why she decided to end her life.

A review of Kamis’ final days revealed that she was afraid of dying alone, struggled to pay for food, faced eviction and feared being institutionalized. She chose to die in the basement of her apartment on her ex-husband’s birthday.

One of these “lessons learned,” as the document puts it, was the case of a 74-year-old blind patient with high blood pressure, a history of stroke, and other health problems.

The man was interested in MAiD because of his vision loss and lack of hope for it to improve.

The official report identified three cases where legal safeguards were not followed: no specialist was consulted on the patient’s non-terminal condition, discussions about alternatives to euthanasia were limited, and the procedure was scheduled to fit the patient’s preferred timing. spouse.

Another non-terminal patient euthanized was Rosina Kamis, 41 years old. Ms Kamis had faced eviction, needed a crowdfunding site to help pay for food and was afraid of “suffering alone”.

She also feared being institutionalized and saw MAID as “the best solution for everyone.”

He suffered from leukemia, but his condition was not terminal. He told his lawyer that he was experiencing “mental suffering,” not physical. The expansion of the law in 2021 made it legal for people like her, who suffer from serious and irremediable medical conditions but whose death is not imminent, to qualify for MAiD.

Ms. Kamis was approved for MAiD and chose to die on September 26, 2021, her ex-husband’s birthday. He died in the basement of his apartment after a doctor gave him a lethal injection.

Lee Landry, 65, is one doctor’s signature away from being approved for MAID despite citing poverty and homelessness as his main reason for wanting to die.

Another Canadian, Lee Landry, 65, told officials overseeing his petition in 2022 that he “doesn’t want to die” but applied for MAiD because he can’t afford to live comfortably. A doctor has given one of the two signatures to allow it.

Mr Landry uses a wheelchair and has several other disabilities that mean he is eligible for MAiD, including epilepsy and diabetes. But until recently he was able to live comfortably, sharing his modest home in Medicine Hat, Alberta, with his service dog.

Changes to his state benefits when he turned 65 in May meant his income was reduced and he now has about $120 a month left after paying for medical bills and essential items. He also faces homelessness.

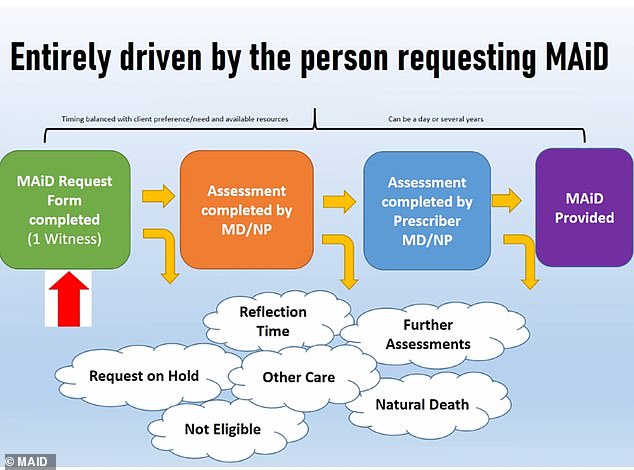

Mr. Landry is awaiting a decision from a second doctor who has evaluated his eligibility. If that doctor rejects the request, Landry says he will simply find another doctor who is willing to approve his death, something that is allowed under Canada’s assisted dying law.

And in 2023, Tracey Thompson, 55, from Toronto, also requested euthanasia after Covid left her out of work and in constant pain for a long time. She told DailyMail.com that she became so tired that she spends around 22 hours a day in bed.

Tracey Thompson, 55, of Toronto, wants to die under Canada’s medical assistance in dying policy.

She told DailyMail.com she can only walk around the block twice a month due to her debilitating symptoms.

In the almost four years that he has been suffering from his illness, he has not been able to work and has been left without his savings. He also has no family to speak of and has lost all his friends.

Now, Ms. Thompson is seeking to end her life through Canada’s assisted dying program, widely considered one of the most permissive in the world.

“My quality of life with this disease is almost non-existent, it’s not a good life,” he told DailyMail.com. ‘I don’t do anything. It’s painfully boring. “It is deeply isolating.”

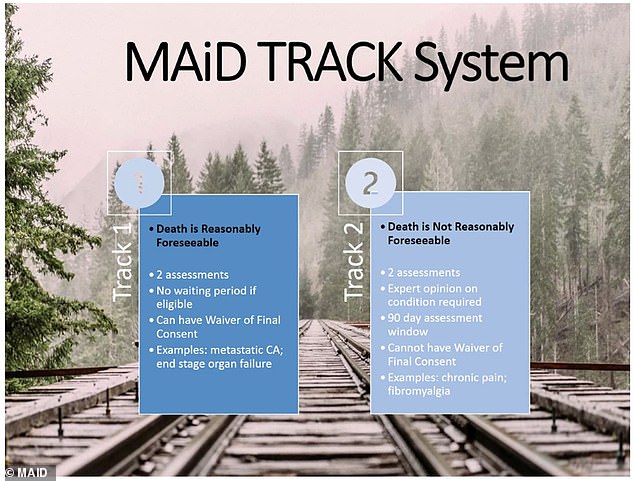

Canada’s health system offers the service even to people whose death “is not reasonably foreseeable.” Pictured: The two-track system allegedly used by Fraser, as indicated in the slideshow.

While doctors are ethically concerned about the number of patients they see die whose deaths would not be imminent, human rights advocates argue that the law restricting MAiD for people with serious mental illness is “discriminatory.”

Dying with Dignity, an end-of-life advocacy group, calls on lawmakers to repeal the mental health exclusion.

But medical professionals have written on forums that the cause of disenfranchised and mentally ill people seeking euthanasia is not hopelessness, but rather a lack of sufficient government safeguards.

One doctor said: ‘I am very uncomfortable with the idea that MAiD is driven by social circumstances.

“I don’t have a good solution for social deprivation either, so I feel pretty useless when I get requests like this.”

As other countries, including the United Kingdom and France, address the issue of allowing MAiD, leaders look to Canada for an example of implementing such a policy.

One slide surprisingly notes that the process to provide MAiD can take “a day”

But many experts in Europe worry that Canadian officials are pushing the boundaries of what is ethically acceptable.

Theo Boer, a professor of health care ethics at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, told the AP: “Canada appears to be offering euthanasia for social reasons, when people don’t have the financial means, which would be a great taboo in Europe”.

“That may be what Canadians want, but they would still benefit from an honest reflection on what’s going on.”

And Kasper Raus, a researcher at the Institute of Bioethics at Ghent University in Belgium, added: ‘The question of who receives euthanasia is a social question. This is a procedure that takes people’s lives, so we must closely monitor any changes in who receives it.

“If not, the entire practice could change and deviate from the reasons we legalized euthanasia.”