<!–

<!–

<!– <!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

Burritos can be a difficult meal to consume gracefully, but a master’s help in looking graceful is at hand, no matter the situation.

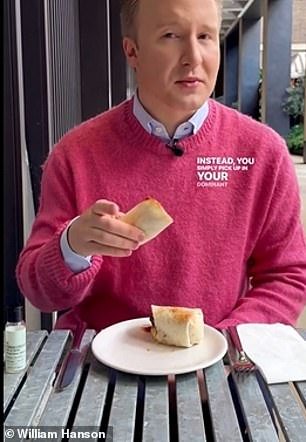

Etiquette expert William Hanson reveals the secret to eating burritos elegantly in a TikTok video which has been viewed almost a million times.

He explains that if the burrito is wrapped in foil, just unwrap the top and leave the rest to “protect it from greasy hands.”

The burrito should then be picked up using your dominant hand, William explains, with the non-dominant hand cupped underneath to catch any “spill” from the open end of the burrito.

We asked William what we were doing with this “spill”.

The burrito should be picked up using your dominant hand, William explains, with the non-dominant hand cupped underneath to catch any “spills.”

He said: “I hope it lands on the plate below. You can leave it there until the end and use a knife and fork to taste it.

“But if no one is watching and you feel like living on the edge, you can use your fingers to pick up and eat.”

Could a knife and fork be deployed in an emergency, due to a particularly awkward burrito?

William noted, “The exact origins of the burrito are slightly unclear, but just like the bread on a sandwich or hamburger bun, the corn tortilla keeps your hands relatively clean when you pick it up to eat.”

We asked William what we were doing with the “spill”. “If no one is watching and you feel like living on the edge, you can use your fingers to pick up and eat,” he said.

“Knives and forks aren’t really meant to be used, but if the burrito was overfilled and leaked everywhere, no one is going to send you to jail for using a knife and fork to enjoy the bits that have now fallen onto the plate.’

And does he have any thoughts on whether or not the restaurant should deliver foil-covered burritos?

William replied: “Foil is not okay in a formal dinner. But in the same way, burritos – as delicious as they are – are not formal foods in British cuisine, so the aluminum point is moot.

“The foil keeps the burrito wrapped and warmer longer, so it serves a purpose.”

To learn more about Mr. Hanson, visit his Tic Tac And Instagram profiles. Her new book, Just Good Manners (Random Penguin House), is released on September 12, 2024. It is billed as “a witty and authoritative guide to British etiquette”, with William sharing “his definitive advice on how to charm and delight those around you in all situations with idiosyncratic authority.”